Image Courtesy Ruvin de Silva

An interesting dimension to the current conflict playing out in Ukraine amidst increasing aggression and spirited defiance, amidst airstrikes, war crimes, sanctions and diplomacy are the varied approaches to the flow of information in and out of the war. Certainly, there is a notable difference in the reporting of Western media outlets and Russian state media; with much having already been said of heritage media’s startling realization that victims of war can be ‘relatively civilized’, or more shockingly, European. Russian state media’s ploy of echoing the Kremlin’s historical revisionism and supporting a ‘special military operation’ to depose a Neo Nazi (and apparently Jewish?) threat in Kyiv elicits no praise for commendable journalism either.

The marked difference here lies in the democratization of media and public dissemination of information. Not just in the manner of how this information is accessed, but also in which such information is produced, curated and shared. Whereas in Russia (for the most part) there exists a singular source of information based on one central narrative on the war, in Ukraine, and elsewhere, such a center of information does not exist. Ukrainian news media covers the war much like how any media outlet would, but what is the discerning dimension of this information war is how social media is leveling the playing field through citizen participation; by being active stakeholders and deterrents against the monopoly of an information hierarchy dominated by governments and powerful media institutes.

The citizen journalist is a creature of 21st century information warfare. A smartphone camera is sufficient to alter perspectives, create new narratives and push back against the old. It has the potential to cause revolutions, both in the online sphere and the offline sphere, and the Russo-Ukrainian war is by all accounts, based on one. In fact, it was arguably the failure of the Russians to win the information war that led to direct military confrontation. It was a social media revolution that helped shift the dynamics of power in the Israel-Palestine conflict, it’s what ignited a mass movement against racial prejudice in 21st century America, and what sparked the Arab Spring in 2011. It empowers everyday citizens as agents for change and as witnesses of history in a world made ripe for citizen journalism.

This new eco system has marked the emergence of a new breed of human; aptly termed the homo digitalis.

“The idea of asking TikTok stars how to fight Russia might sound like a joke, but remember they said the same thing about the radio in World War II. Never underestimate the power of technology, and how it reaches young people in ways you can never understand. Tik Tok isn’t some childish gimmick, it has more power and more influence than the Nightly news.”

This was an impassioned plea during the cold open from this weekend’s episode of Saturday Night Live. Social Media’s role in fueling change is so obvious and relevant that it provides material for satire.

Marta Vasyuta, an overnight Ukrainian TikTok star, is well ahead of the curve. Although she lives in the United Kingdom, her curated stream of TikToks have garnered her millions of views and helped her bring the destruction of Ukrainian cities to the social media feeds of a younger demographic, whose primary interests probably don’t include geopolitics and urban warfare. Marta, in every sense, is part of this new breed of citizen journalist, war correspondent and real time reporter. Her method might not tick all the boxes, nor would it impress journalism purists. Her approach is by no means new either. Farah Baker, a 16 year old Gazan, almost single handedly turned the tide against Israel’s military might and altered the war of narratives through her real time tweets in Gaza during the 2014 Israeli offensive. Yet, while Marta’s coverage of events in Ukraine might not even be in real time or offer her firsthand experience, her curation of videos is still extremely relevant considering the broader scope of the conflict and how important a stakeholder people like her are in the context of how information around these environments flow, and how the outside world reacts to it.

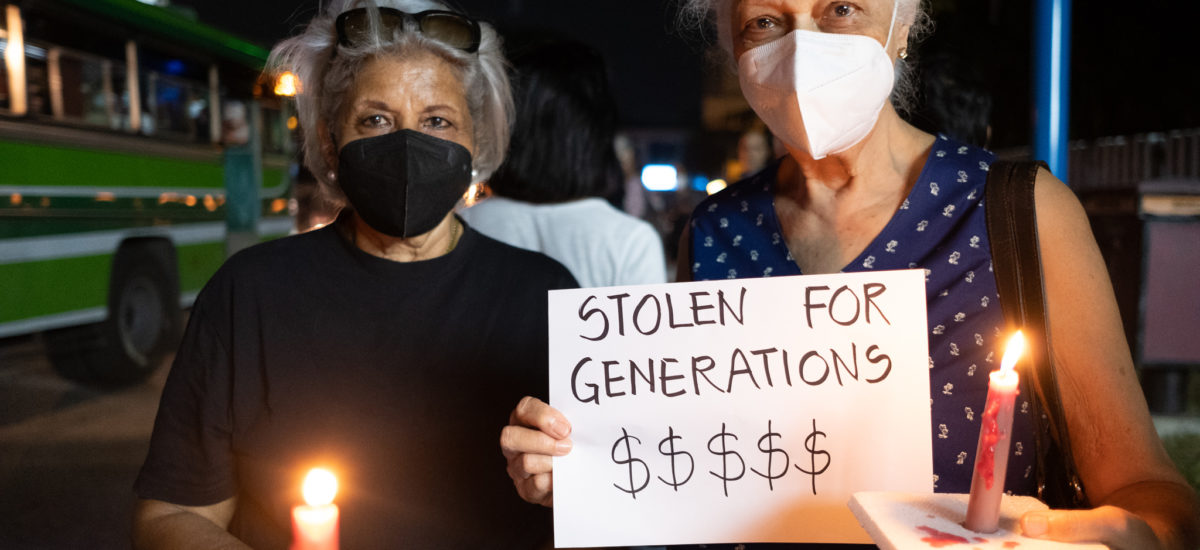

Sri Lanka in this regard has better experience dealing with the ills of this social media revolution. Where the failure to check the spread of fake news and hate speech (from Aluthgama to Digana, and the post Easter Sunday climate) allowed for the spilling of violence from the internet onto the street. It is this concern that has widely dominated any discourse on social media cohesion in Sri Lanka since then, and rightly so. Yet to what degree does it allow for a collective effort to fight against injustice, prejudice, and mobilize popular support, and effect change for the better? The question is an interesting one to consider on a week where #GoHomeGota is a trending hashtag on Twitter and an islandwide citizens protests against the government’s incompetence enters yet another week.

One of the most successful examples of concerted social media activism and advocacy in Sri Lanka followed the arrest of minority rights activist Hejaaz Hizbulah. Following his arrest, in May 2020, a social media campaign called JusticeforHejaaz began documenting case updates, flagging support for Hejaaz, and in general advocating for his immediate release. The platform was largely successful in how its updates were picked up by local media, civil society organizations and importantly, international NGOs such as Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch. In July 2021, Hejaaz was named a prisoner of conscience by Amnesty International which brought further attention to his case and also brought more attention to the arbitrary and draconian nature of the Prevention of Terrorism Act.

During groundviews’ interview with Hejaaz’s wife Maram, she spoke of how important the social media angle was, in its ability to connect with and engage with other actors advocating for the improvement in Sri Lanka’ human rights situation. All of which resulted in international pressure and the rallying of support behind Hejaaz’s cause, eventually leading to his release within two years. An anomaly considering PTA detainees are often jailed for much longer periods of time.

Dr. Sanjana Hattotuwa’s analysis of tweets tagging the JusticeforHejaaz page and its hashtags, provides great insight into the degree of social media cohesion the page was responsible for. His thread detailing the above can be viewed here.

The Revolution in Action

In 2014, the overthrow of Ukraine’s Pro Putin President Viktor Yanukovych was sparked thanks to a Facebook post by Ukrainian journalist Mustafa Nayyem who urged people to gather at the Maidan Square in central Kyiv to protest against Yanukovych’s sudden backtracking of a decision to sign the European Union–Ukraine Association Agreement.

“Well, let’s get serious,” he wrote. “Who today is ready to come to Maidan before midnight? ‘Likes’ don’t count. Only comments under this post with the words, ‘I am ready.’ As soon as we get more than a thousand, we will organize ourselves.”

The call was heard and what started as a couple hundred protestors soon turned into an overwhelming show of what powers social media can wield. Protesters occupied the square and refused to leave until their concerns were addressed. Yanukovych, taking a leaf out of the Chinese Communist Party’s response to the Tiananmen Square protests, responded with violence and force, and when the people did not back down, Kyiv for the first time in the past decade became a war zone. The protestors persevered, Yanukovych fled for Russia, Russia annexed Crimea and the Donbass region broke away from Ukraine, and Ukraine grew ever closer to the West. The rest of the story is playing out right before our eyes.

It was one of the first examples of the homo digitalis effecting revolutionary change on the world stage.

The worldwide protests following the murder of George Floyd was another such example that saw the wide-ranging homo digitalis effect. All of which was sparked by mobile phone footage of Floyd slowly succumbing to the force exerted to his neck by a white policeman. Darnella Frazier who shot the widely circulated video, in doing so dramatically altered the world with what she had shared. It asked why such prejudice and deep-rooted racism still existed so long after the civil rights movement and after the country twice elected a black president. Like the television did for Rodney King, the mobile phone did for George Floyd. The stand on race was brought to the forefront of every conversation, and it spilled into the social media feeds of many young Sri Lankans too, who took a month-long stance against racial prejudice in America.

This doesn’t speak to some form of blind infatuation with socio-political events in the United States when similar strands of racism exist at home, but rather to the power social media can have in reaching those that aren’t open or awake to the injustices spoken of in highly analytical reports, or mundane news briefings. Social media advocacy on movements like these will no doubt help bring attention to the issues that really need them, to date however, popular support for issues in Sri Lanka have unfortunately failed to materialize on a larger scale. It implies to an extent of how this level of cohesion has not yet been reached amongst Sri Lanka’s social media users. Yet things are likely to change. The government’s land grabbing efforts in Uva Wellassa were met with a massive show of force by the local community, it remains to be seen to what degree the movement can be sustained and reach a larger community online. Surely if #FreePalestine can trend in Sri Lanka, so can #FightForRidimalliyadda.

We live in an era where an unwitting observer can compress thousands of academic essays, analytical reports and pundit opinions into a single Instagram post or a 140-character tweet to bring an empire to ground or an ideology to dust; that’s where 21st century people power resides, and so we find the political hierarchy in Sri Lanka at the brink of realizing this. Years of mismanagement, corruption, family rule and favouritism has come to a head. Something’s got to give, and when it eventually does, you can be sure that a mobile phone in somebody’s backpocket will show the world how it pans out.