Image Courtesy of Global Press Journal

In early 2021, a survey conducted by the International Food Policy Research Institute, found that farmers faced food insecurity as a result of the measures that had been put into place to curb the spread of Covid-19. Of the farmers surveyed in the published findings, usual crop cultivation and farming was affected to the extent where 42% of the respondents were hampered by stay at home orders, 33% in being unable to purchase inputs and 56% citing a lack in market demand. In summary the report said that “High levels of food insecurity and disruptions across domains such as income, asset ownership, and agriculture could have short- and long-term effects on people’s health, nutrition and wellbeing.”

This report surveyed its respondents between December 2020 and February 2021. It is a safe assumption that the above conclusion did not take into consideration the impact of the potential see-sawing of policy that was to ensue.

To ban or not to ban chemical fertilizers has been at the forefront of President Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s agenda since the run up to his election victory in 2019. In June this year, as divine affirmation of this promise, the President confirmed to the Mahanayake of the Asgiri Chapter and other senior Buddhist clergy that come hell or high water, Sri Lanka will not go back on the ban on chemical fertilizers.

In July, Basil Rajapaksa entered Parliament. Also in July, the ban was “relaxed”.

Even before this intervention by brother, the concerns around what sort of impact a sudden transition from chemical fertilizer to organic farming practices could result in was very much in the public discourse. Among the issues spoken of was the lack of preparation and training farmers (who for years had used chemical fertilizers) had to switch to more sustainable farming practices within such a short span of time. The effect this sudden change would have on the food production cycle was almost evident beyond prediction, with farmers protesting such short sighted agricultural policies and experts saying that adding imported organic fertilizer to soil that has been heavy with chemical fertilizers could have a dramatically worse impact and adverse environmental effects.

The decision to switch to organic farming was not without its promoters. As government officials proclaim time and time again, $400 million a year could be saved by stopping the importing of all manner of chemical fertilizers and pesticides. The funds that go into securing such fertilizers and flow out of the country into some pesticide producing company and away from the farmer who toils in his field could be invested back into the farmer and the soil that produces his or her crop.

The proposed change was also well received by some, including those well versed in the practice, skill and dedication it takes to invest and inculcate such organic farming practices. One supporter, prominent agriculturalist Thilak Kandegama, applauded the government for a historic step in the right direction. By Mr. Kandegama’s estimate, those who do not know and are not willing to engage in organic farming should not discourage the people who are willing to learn and willing to engage in it.

And what of those that are willing to learn?

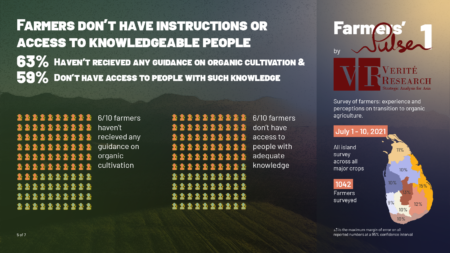

A survey conducted by Verité Research called Farmers Pulse (the results of which are available to the public) spoke to farmers in an attempt to get an understanding of where they were placed with regards to the sudden policy change and the expected impact of it. It proved to be the first such time that the perspective of Sri Lankan farmers on this policy was presented based on statistically representative island wide survey results.

Of the farmers surveyed, 90% confirmed their use of chemical fertilizers in farming and 85% of them expected sizable reductions in their harvest if they are not allowed to use chemical fertilizer. The survey also touched on crop reduction experienced by farmers, with 44% experiencing a decline and a further 85% expecting a decline in the future harvests due to a variety of factors.

The major finding of the survey was that farmers overwhelmingly supported the transition to organic farming, yet all the same required the time and the guidance to make a realistic and feasible transition, which (as the data indicates) had not been done.

It begs to question why, in the face of economic hardship brought about by COVID-19 that is only now starting to take its toll, the prospect of producing a food shortage looked appealing to the ruling party. As was detailed before and has been done more thoroughly elsewhere, the switch to organic farming is a step in the right direction. However, if taken at the wrong time and fueled by rhetoric and not well thought out policy and lacking co-operation of the farming community, one step is all that might be needed for a nose dive down a precipice.

For more on this issue read Vidura Munasinghe’s article here.