Photo courtesy of Namal Kamalgoda

The Sinharaja Rainforest has been in the public eye for a few weeks now. Is it being threatened by encroachment and development? Will it lose its UNESCO World Heritage status? Are there new hotel projects on its boundary? Will the Government construct reservoirs in its forests? Or, as the State media asserts, is this fake news expounded by environmentalists – political opponents of the government – with vested interests of their own?

The wave of controversy sparked by the emotional outburst of teenage Bhagya Abhayaratne from Rakwana on prime time TV that Sinharaja is being destroyed in clear view of its official protectors brought to focus a number of long-buried issues that plague this jewel of our conservation portfolio. This article attempts to put into perspective Sinharaja’s conservation status, the current controversies and bring into focus some of the long-standing issues related to managing the land in and around the Sinharaja Forest Complex.

The Good: The protected area is larger than it ever was before

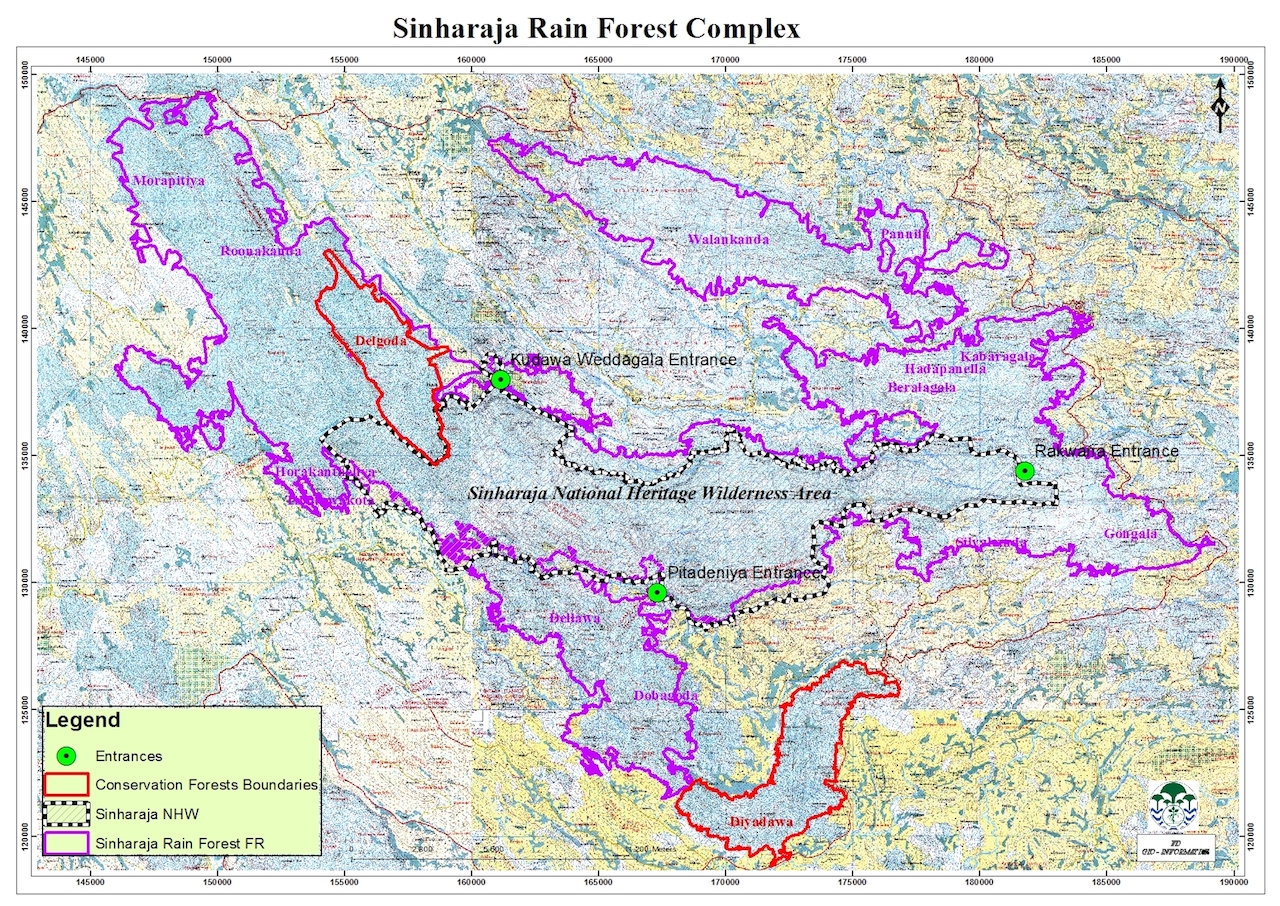

In 2019, the Forest Department protected, under gazette, 25, 000 additional hectares of forests around Sinharaja, strengthening the protection of the core World Heritage Wilderness area. This increased the entire Sinharaja Complex to approximately 36,000 hectares. The gazette described nine peripheral forests that would be annexed to the complex – including Dellawa in the south, Morapitiya – Runakanda and Handapanella in the north, Ayagama in the west and Gongala and Delgoda in the east. This was the culmination of almost 20 years of mapping, ground surveying and demarcating of boundaries.

The Sinharaja Complex of forests is the largest, and one of the most critical, protected areas in the Wet Zone of Sri Lanka. It is the last remaining, relatively undisturbed, remnant of a tropical humid evergreen forest. Straddled between the Ratnapura, Matara, Kalutara and Galle Districts, the forest complex spreads in an east-west direction along the southern end of the central highlands. It harbours virgin rainforests that have evolved over many millions of years – much of its core remains untouched by human hand and harbours many rare species found nowhere else on earth. The trees, ferns, shrubs and lianas found here are Gondwanaland relics and contribute greatly to our scientific understanding of continental drift. A geological feature of considerable interest is the presence of the Sinharaja Basic Zone, with the reserve located within the transition zone of two important rock types characteristic of Sri Lanka; the South-western Group and the Highland Group. UNESCO recognizes Sinharaja as an outstanding site for the study of the processes of biological and geological evolution. The park lies within a Conservation International-designated Conservation Hotspot, in a WWF Global 200 Freshwater Eco-region and is one of the world’s Endemic Bird Areas.

(Map from Forest Department)

Sinharaja: a place of unparalleled biodiversity

The south-west of Sri Lanka is generally high in biodiversity and endemicity. These rainforests, therefore, harbour many unique species found, at times, only in its rain-drenched forest clad depths. It is recorded that 64 percent of Sri Lanka’s endemic trees are found here. Of 26 endemic birds, 25 are found in Sinharaja. Endemicity among mammals and reptiles is also over 50 percent. The endemic purple faced leaf monkey and its rare silver-tinged cousin are found in these forests. Species are still being discovered. The colourful Sinharaja tree snake, discovered a few years ago, and the rare orchid Gastrodia gunatillekeorum, described in 2020, demonstrate the yet undiscovered potential of this forest to yield new species and knowledge to science.

Even the British Colonial authorities, who were otherwise ready to wield their axe to clear forests for plantations, recognized the importance of conserving this pristine rainforest. In 1875, and later in 1926, a Government gazette recognised the Sinharaja Jungle (Mukalana) as a natural forest for protection. In 1988, 11, 200 ha of forest was included under the National Heritage and Wilderness Area Act. The same year, 8,864 ha of its oldest and most pristine area were elevated to a UNESCO World Heritage Wilderness site. Since then, the boundaries of the reserve have expanded. The status of the newly annexed forest complex – as a Reserve Forest – allows traditional human exploitation and sustainable use of the forest, such as tapping of the kitul palm (Caryota urens), collecting of medicinal herbs and of rattan (Calamus rotang).

Draining to both the south and the north, an intricate matrix of waterways flow into the Gin and Nilwala rivers on the southern boundary; and into the Kalu Ganga (river), via the Napola Dola, Koskulana Ganga and Kudawa Ganga, on its northern boundary. The complex is fed by both the south-west monsoon (May-July) and the north-east monsoon (November-January), and annual rainfall ranges from 3,500-5,000 mm with no real dry season. This creates a perfect watershed for these three important rivers.

The Bad: Encroachment is a real threat and land use conflicts are rife

Historically, the core of Sinharaja has remained untouched due to its steep terrain, inhospitable jungle and lack of access. From 1875, it was afforded government protection and the larger tea estates that formed its boundary on the northern and eastern sides, kept encroachment at bay. However, the forest lies on a strip 7 km wide and 25 km long with peripheral forests to the north and south, with towns and villages nestled in between the protected forests. The Sinharaja Complex’s protection is compromised by this vast and porous boundary – stretching across four districts and many divisions. Smallholder tea cultivations, gem mining, agriculture expansion, roads, mini hydro-power projects and hotel developments dot its boundary. Along the southern and south-western boundaries, forest encroachment by smallholder tea cultivations, illegal gem mining and settlements is fairly common. Environmental groups like Rainforest Protectors, who are based in the locality, record numerous examples of maldevelopment on the periphery, identifying specific sites, lands, and locations. The lack of controls of development activities, along the forest periphery, impedes the connectivity and integrity of the forest landscape.

In the early 1990s, there were approximately 7,000 people living in the villages that border the forest. By 2020, this population had increased by three fold and more land had been taken by the expanding smallholder tea cultivators. As population pressure increased, the cry for infrastructure – roads and bridges for larger transport vehicles – to connect hitherto unconnected villages and rural areas to nearby towns became louder. The edge effects around roads are numerous as they bring in litter, poaching, extraction of rare species (orchids/fish), introduce invasive species and create conditions for further expansion of adjacent settlements. The growth of both domestic and international tourism, in the last ten years, has led to a number of hotel and eco-lodge developments around the periphery of the protected area. Much of this development is outside of any formal eco-tourism guideline and generally greenwashes an ill-conceived construction and product, paying little heed to the principles that govern good eco-tourism ventures.

Mini hydro power projects

In the 2000s, mini hydropower projects were promoted with concessional development financing and attractive buy-back rates, which attracted huge interest from investors. The possibility of earning international carbon credits was an added incentive. For many years mini hydros that were located deep in the forested areas were lauded as sources of clean renewable energy. They have since run into controversy as their negative impact on stream flows, streamside vegetation, waterfalls, fish and aquatic fauna became apparent. The question of the real cost of this renewable resource, and the growing outcry against such projects from downstream communities and environmental groups, has now forced government to reconsider their pending licenses. Signs of stress on the watershed are already visible and due to stream drying and pollution from agriculture and illegal gemming, some villages in Kalawana and Godakawela DS are being provided drinking water by bowser. A sad plight for people living in the watershed.

Today, the Sinharaja Complex sits within a mosaic of development of tea cultivations, villages, roads, mini hydros, drinking water schemes, housing projects, factories, religious institutions, burgeoning towns, et al. The forest’s extensive populous boundary makes it a challenge for the Forest Department to exercise forest management. This is compounded by the lack of sufficient field staff for patrols.

Village involvement in forest management is also low. Typically, Sri Lanka’s conservation agencies have poor community outreach and are prone to take the ‘stick’ approach, using regulations and punitive actions to prevent forest crime. This results in a lack of communication and collaboration between village and protected area managers. The typical villagers of this area are not forest dependent for their livelihoods – other than kitul tapping, rattan collecting and medicinal herb collection. Some jobs have been created by forest-based eco-tourism – guides and trackers for visitors – but in insufficient number to provide substantial revenue opportunities through sustainable, nature-based tourism. This lack of appreciation of the forest that is their backyard, persistent poverty and social isolation, and the disconnect between forest managers and the village community, leads to a proliferation of crime along the length of the boundary.

The Ugly: Controversial projects and questionable development

The widening of a road from an ancient, forest-bound village, Lankagama, to the adjoining Neluwa town created controversy. An old proposal to build water supply reservoirs within the conservation area to supply water to thirsty dry-zone towns on the southern coast were dusted up, despite it being criticized by the Government’s own safeguard agencies nearly seven years ago. Most eyebrows were raised, however, and media minutes consumed in the aftermath of an outburst by a nineteen year old young woman from Rakwana, who claimed she witnessed the destruction and depletion of the rainforest every day on her way to school and back! It was not so much her statement but the overreaction of the Government in handling it that ignited media frenzy. By sending the police to question the teenager on the sources of her information and officials of the Forest Department to vehemently counter her claims of deforestation, the Government unleashed an avalanche of negative public opinion upon itself.

The central theme of the young woman’s statement was that the government is turning a blind eye to repeated incidents of forest clearing and tree felling all around her village, straddled in the narrow spit of land between Sinharaja core heritage area and the peripheral Walankanda forest. She pointed out, as an example, the clearing of all trees on a land along the main Rakwana-Pothupitiya road – an area where the few remaining rainforest elephants roam. Villagers in the area believe that a hotel is being constructed on this land without the necessary approvals. The media and environmental groups revealed that the development in question was owned by the children of a well-known gem merchant and that vegetation had been cleared from a large extent of land.

The Forest Department took its share of flack over the way its officials bullied the young women in question, at her own home. Nishantha Edirisinha, a senior official from the Department, pointed out that the Sinharaja Core World Heritage wilderness area is almost four km away from the site in question. According to him, this is private land – a part of a larger private holding – which has been cleared and developed for three (possibly large) private houses. He stated that this area is not protected under the law nor declared as an elephant corridor. Private land holding and development is governed by normal regulations applicable anywhere in the country. This is despite the land in question being sandwiched between two of the largest component forests of the Sinharaja Complex. Mr. Edirisinha pointed out that the issue of managing other lands adjacent to the forest comes up time and again.

As in the previous examples of the Lankagama road and the reservoirs in the forest, the Government is quick to discredit the messenger by claiming that the development is outside the protected area and hence allowed or to dismiss the problems of forest loss claiming it would be compensated for by releasing land for afforestation. Historically, other than a scattering of old, traditional villages, the Sinharaja boundary had no private lands, save for tea estates. The confusion that reigns today is due to the Land Reform Commission’s policies and practices of doling out the land it acquired in the 1970s under the Land Reform Act to individuals and businesses for dubious purpose. In 1994, then President Chandrika Bandaranaike requested the Land Reform Commission to hand over the management of around 2,500 ha of forested lands to the Forest Department for its annexure to the Sinharaja Protected Area network. Despite stating its intention to do so, the LRC had held on to this land and have steadily released plots of this forest to developers.

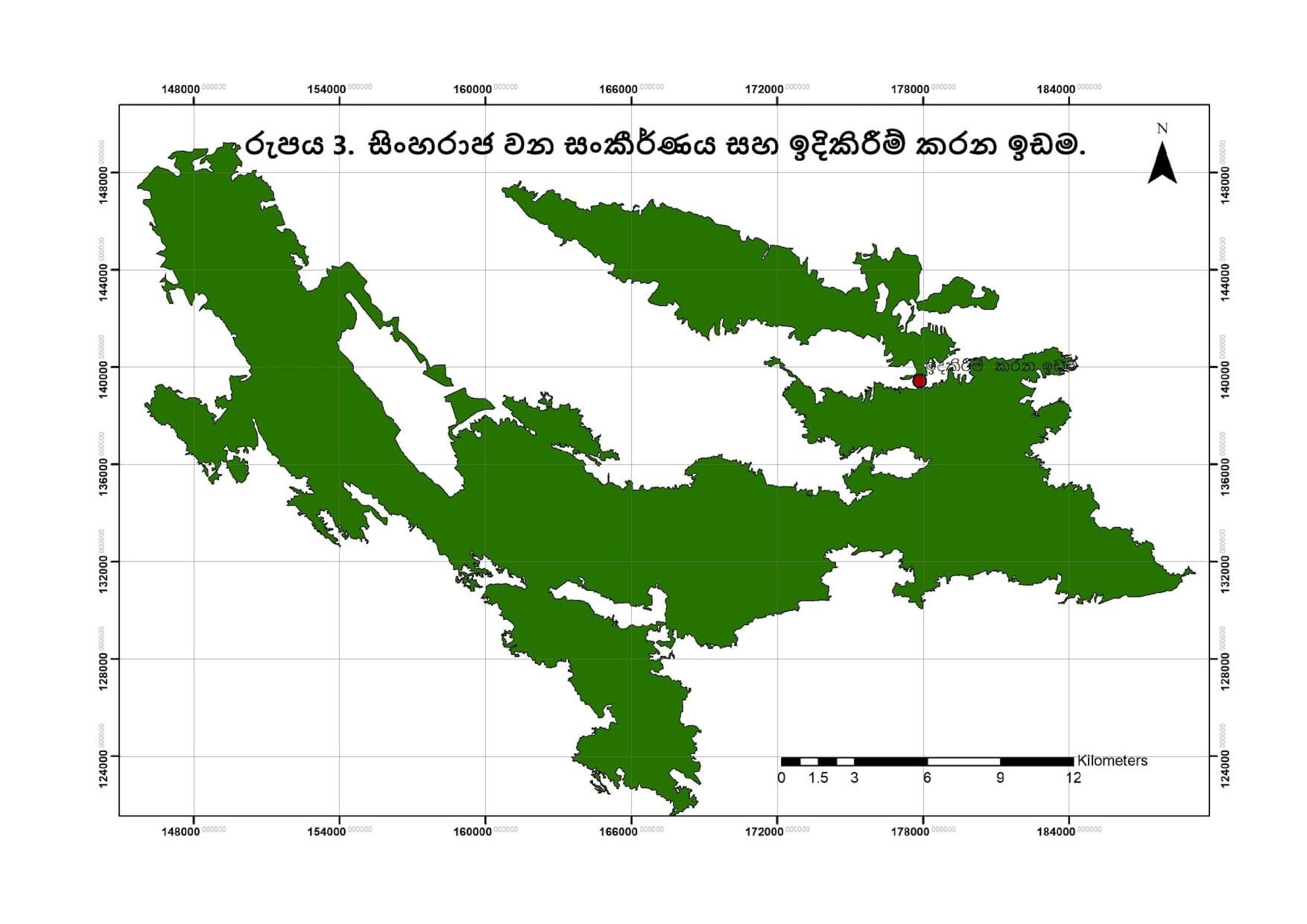

The hotel site in question (red dot) is sandwiched between two large conservation areas of Sinharaja Complex

Will Sinharaja lose its status?

Sinharaja’s conservation was strengthened recently with the annexure of all the peripheral forest reserves. If the Government persists in its efforts to augment the drinking water supply to Hambantota, by creating new reservoirs in the forests, it could pose a real threat to its status. Last year, the Cabinet of Ministers agreed to expedite the Gin-Nilwala Project to annually provide a total of 122 million cubic meters of drinking and industrial water to the Hambantota District through two trans-basin transfers (from the Gin to the Nilwala and then to the Walawe). The project will benefit areas such as the Katuwana, Mulatiyana, Okewela, Tangalle, Beliatta, Angunukolapelessa, Suriyawewa, Ambalanthota and Hambanthota Divisional Secretary Divisions and approximately 100,000 people will benefit from it. The proposed project also envisages providing industrial water for the Greater Hambantota Development Area including the Mattala Airport, Hambantota Port and Industrial Zone. In 2017, the first phase of the project, the detailed feasibility study, was contracted to the China CAMC Engineering Co. Ltd. An Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) has not been furnished as yet.

The major constructions that will affect Sinharaja are the series of cascading reservoirs and their connecting tunnels, 37 km of them. Three reservoirs are proposed – the largest at Madugate, then Kotapola and finally Ampanagala – from where water will be transmitted to an existing irrigation tank called Muruthawela. The total forest loss is presented as minimal (10-15 acres) but this is not the total damage that will be wrought on the conservation area. Roads will be cut and heavy machinery will trammel through the virgin rainforests bringing in people and invasive species with them. The tunnelling will have unknown impacts, and after the infamous collapse of the Uma Oya tunnel (another project to augment water for Hambantota), we should be especially wary of construction companies that drill through the mountains. The tapping of rivers at their source and inter-basin transfers can have impact on downstream communities who are already feeling the effects of water shortages and early stream drying. It can also alter the hydrology of two important rivers. Whether these impacts have been sufficiently studied and necessary safeguards set in place are yet to be seen in a published feasibility report.

The moot point is what kind of environmental damage and forest loss are we going to tolerate to supply more and more water to the south? What kind of industrial and township development are we promoting in this region, which remains agricultural and poor despite the high investments in infrastructure to promote industry, tourism and urbanization?

Next installment – The Legal Case: Sinharaja has multiple blankets of protection but how do they work?

The writer is a former journalist, a freelance consultant for environmental policy and Trustee of the Federation of Environmental Organisations