Editor’s Note: These are excerpts from a long-form story on the experiences and reflections of Muslim families in Akurana, Ambatenne, Pallekele, Digana and Katugastota, three months after a series of violent attacks against their communities. Groundviews visited these areas in the first week of June 2018.

Individuals whose homes and businesses were damaged by Sinhala-Buddhist extremist mobs spoke with increasing frustration of the inadequate State response to the violence. They also outlined the probable causes that would motivate these groups to wreak this violence.

In order to ensure attention to key issues, we are publishing each as an excerpt.

‘How do you explain this to an eight-year old, and do you explain it at all?’ Nusra asks. Two of her three children watched their grandfather’s shop set on fire by people she told them are ‘bullies who were just being mean’, with no identifiers of Sinhalese and Muslim. ‘I don’t want to make them aware, at this young age, of these tensions and divisions, I worry they’ll carry it into their later lives’.

In this way, the violence in March has an impact that will linger long after the last damaged home has been rebuilt. The events in Kandy effectively exposed a younger generation to violence, even though many may be too young to fully understand its implications.

Among those affected, there is disappointment in knowing that the threats came from, literally, close to home. There is also indignance that impunity reigned for as long as it did, with arrests being made only after four days of riots. Suspects remain in remand, and there have been no convictions yet.

These stories are vastly different to those that were breaking during the ongoing violence. ‘Buses of people coming from far away’, while occasional, do not seem to be those that the community identify as heavily responsible. Given the observations of the affected and the patterns that the attacks followed, these incidents cannot be written off as purely ‘racism’.

The actions of those from nearby villages, some with intimate knowledge of an individual’s economic standing and possessions, points to a premeditation that was not necessarily informed by the death of M.G Kumarasinghe in Teldeniya. In addition, the nature of the posters placed around the shops, calling for the boycott of Muslim businesses, could reinforce the fact that there is possibly an economic motivation for the attackers.

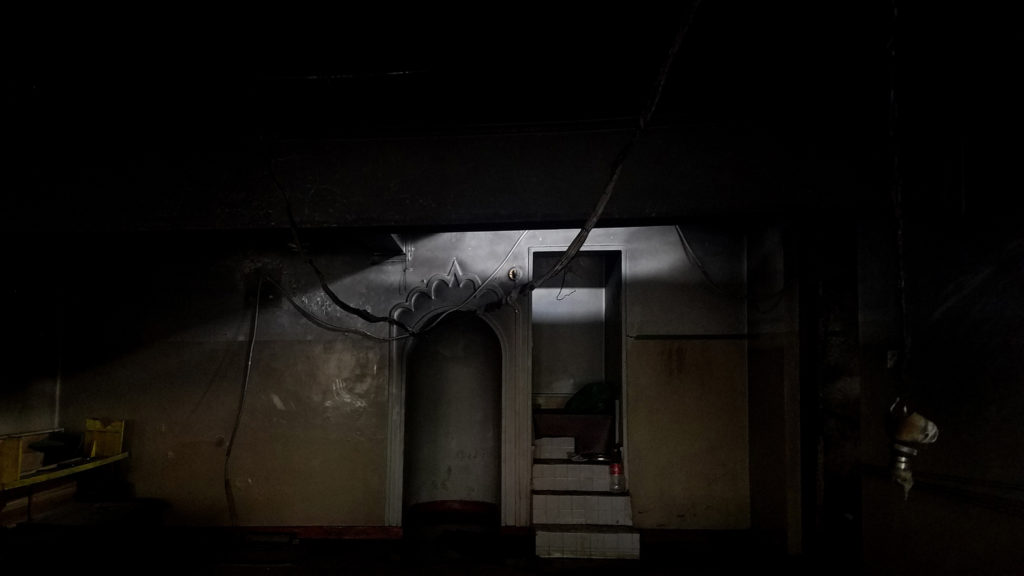

(Note: the linked photo was captured in the Western Province and is a variant of those seen by the shopowners in Digana – it as not captured in the area.)

‘They do this because they know that they will not be caught, and will go unpunished,’ says Cassim. Sri Lanka’s history of violence by extremist groups against minorities serves to highlight how important it is that justice is meted out to those responsible. Some of the affected individuals note that the impunity enjoyed by the rioters in Aluthgama in 2014, Black July in 1983 and as far back as the Sinhala-Muslim riots of 1915 serves to legitimise the extremists.

Nizar in heartened by the community’s response to their struggle but he hopes for a future where minorities don’t live with the fear of being possible targets of hate within the country they call home. ‘I have seen four such riots in my lifetime,’ he says ‘and I hope I won’t have to see another.’

Read the full story here.