Photograph courtesy IPS

Context

The next round of elections to local government in Sri Lanka is scheduled for February 10, 2018. The election is significant for many reasons. It is being held after several postponements; it is the first elections to be held by the National Unity government since it’s election to power in August 2015; it is the first elections to be held under the new hybrid electoral system introduced at local government level in 2012 as amended in 2017. It is also significant for another reason. It is the first election to be held which puts into operation a mandatory 25% quota for women in local government. While much can be written and said about the history and politics of electoral reform at local level in Sri Lanka and the upcoming elections, here we confine ourselves to the quota for women.

Brief History

Local government has a long history in Sri Lanka going back to 1946. This system was given a new lease of life with the introduction of a three tier system of local government comprising Pradeshiya Sabhas, Urban Councils and Municipal Councils in 1977. The electoral system to local government also shifted from a ward based simple majority system of elections to elections based on proportional representation and a list system in 1977 (first implemented in 1989). A hybrid system of elections, which combined first past the post (Ward) and proportional representation (PR) was introduced in 2012, in an effort to redress the anomalies of proportional representation (PR) and re-introduce the positive elements of ward based elections abandoned in 1989. A further amendment of the local Authorities Elections Act in 2017 (The Local Authorities Elections (Amendment) Act No. 16 of 2017) now ensures that local councilors are elected according to a proportional representation system where 60% of members represent single member or multi member wards and 40% are returned from a list called the ‘additional persons’ list without a ward based constituency. The total number of members in local government has been increased from 4486 to around 8356 members. In terms of Section 27F of the Amendment, 25% of the total number of members in each local authority shall be women members.

The Mixed Member Proportionate Electoral System and a Quota for Women

Under this new system, each political party submits two nomination papers – the first nominations paper comprises members who are assigned a ward within each local authority area (LAA). At least 10% of the members assigned a ward have to be women. The second paper is the additional persons list and 50% of those in this list have to be women. It should however be noted that each voter only casts one vote for a political party candidate or independent group candidate of their choice at the ward level. At the conclusion of the elections, all votes obtained by a political party or independent group in the local authority area comprising several wards are aggregated to determine the total number of members from both the wards and the additional persons list that each party is entitled to. This is done by the Elections Commissioner, once election results are finalized.

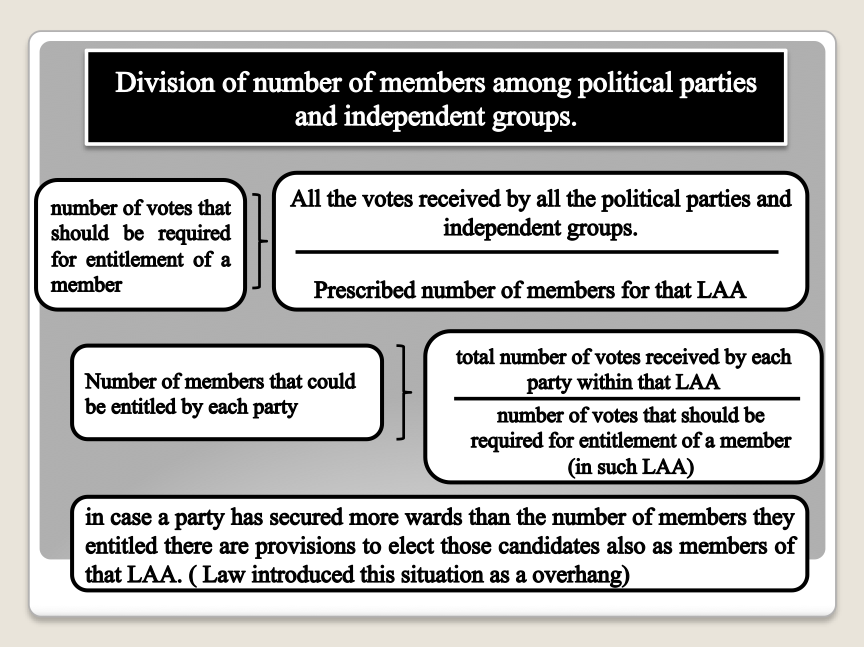

In order to do so, the Commissioner must first determine the number of votes required for entitlement of a member. This is computed by dividing the total number of votes received by all parties and independent groups by the prescribed number of members of each local authority (this number is gazetted). The total number of votes received by each political party/independent group is then divided by the number of votes required for entitlement of a member to ascertain the number of members elected by each party.

Source: Gayani Prematileke, Legal Officer, Ministry of Local Government.

In case a party has secured less wards than the number of members they are entitled to, those number of members (shortfalls) are selected from the candidates of the first nomination paper who contested and lost their seats or from the additional persons list.

Each political party’s obligation towards the 25% quota for women is determined after these computations are completed by the Commissioner of Elections, taking into account how many women were elected to a local authority at the ward level. Once this number is known, the Commissioner will decide how many women have to be put forward from the additional persons list of each political party or independent group to ensure 25% of women within each local council.

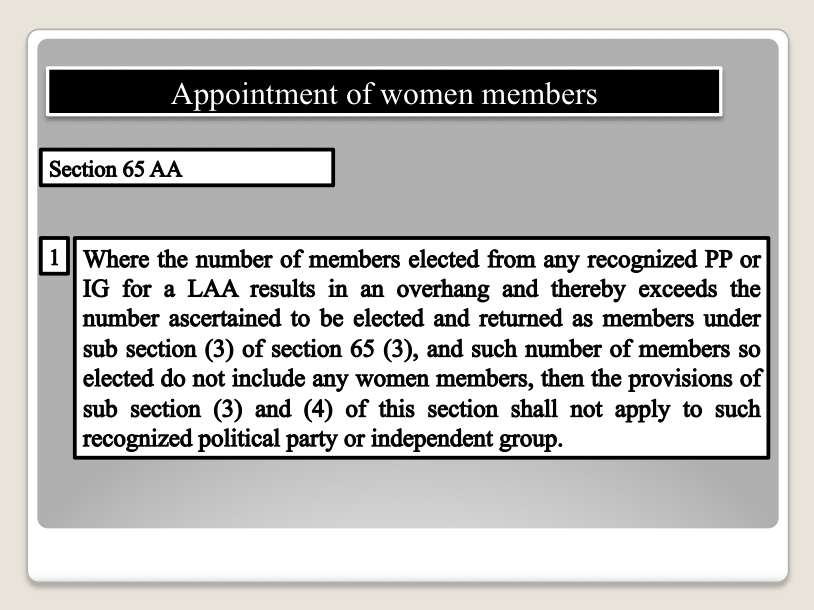

If the number of members elected from a political party results in an ‘overhang’ and thereby exceeds the number ascertained to be elected as members and such number of members do not include any women members, then the 25% women’s representation is secured through the PR seats of other political parties. Similarly, if a political party or independent group has received less than 20% of votes in a local authority area and is entitled to less than 3 members, they are also exempt from appointing women from the additional persons list.

Source: Gayani Prematilleke, Legal Officer, Ministry of Local Government.

As a result, the obligation of fulfilling women’s representations within local authorities in terms of this new quota may fall on the parties receiving the next highest number of votes rather than the party winning the majority of votes.

The significance of this quota

This quota is the result of a long struggle waged by women’s activists, organisations and the National Committee on Women (NCW) going back almost 20 years, to address the under-representation of women in politics in general and in local government in particular. Women’s representation in local government in Sri Lanka has historically been extremely low and has never exceeded 2% due to the dominance of a patriarchal culture within political parties and the extremely low nominations for women at elections. For instance, nominations for women by the major alliances/parties in the past has generally tended to be somewhere between 4% to 10%.

The formal or official consultations to shift from the PR system to a mixed system which began in the early 2000s and went on for over a decade, was mainly centered on balancing the needs and interests of larger established political parties and how to safeguard the status quo, particularly in terms of protecting the historical patterns of representation, voter base and voting patterns and more equitable representation for minority parties. Incredibly, this process completely ignored the needs of other historically marginalized groups or constituencies, in particular youth and women from representative politics, and the consistent demand for redressing the marginalisation and discrimination experienced by women through all the various electoral reforms. In fact, the 2012 law, which put into place the hybrid system completely did away with the 40% mandatory quota for youth candidates between the ages of 18 and 35 and instead introduced a 25% discretionary quota for women and youth, which political parties could have ignored without any consequences.

The new electoral system offers us an opportunity to democratize politics starting at the local level by paving the way for closer engagement between the people and their representatives at the ward level. Moreover, the women’s mandatory quota offers a historic opportunity to bring women in to the public domain of representative politics, increase women’s participation in politics, change public perceptions about women’s ability to do politics and break with the now entrenched political culture of big spending in politics, patronage, corruption and violence.

The importance of this quota and the 25% representation that it ensures for women cannot therefore be overemphasized. Yet there are still some troubling aspects in its formulation and its operation. While the quota will significantly increase the number of women in local authorities, it does not materially challenge the status quo of male incumbency. While the bulk of seats (60%) are contested at the ward level, only 10% of these seats or wards are available to women. Winning a ward is an assurance of a seat and the smaller constituency of the ward allows for easier and cheaper campaigning and familiarity with a vote base. The majority of women will be appointed from the list, and will not therefore have their own constituency and will also be robbed of the opportunity of building up a constituency and relationships with voters. They will be perceived as not being accountable to anyone and may not be taken seriously which will hinder their efficient and equal participation within local authorities.

The onus of naming women to contest wards, the selection of wards that women are given nominations for and the inclusion of women’s names in the PR list is held by the party, in particular party organisers at local and district level, the vast majority of who are male. This system remains unchallenged and women will be dependent on those who wield political power within their parties for nominations and appointments from the PR list following the elections.

While all those contesting wards can win their seats if their party polls the majority of votes, those appointed from the additional persons list have no certainty of the basis on which they can secure a seat. They are also required to campaign beyond the confines of a ward in the entire Local Authority area and will bring in the bulk of the votes to a party. Therefore women will be required to do more campaigning but will have no assurance of a seat. Continuing misogyny within political parties has also meant that men perceive women as interlopers and the 25% an undue advantage, which has resulted in women on the campaign trail receiving threats and being intimidated by fellow male candidates competing for seats on the PR list. Furthermore, as explained above, ultimately the responsibility of ensuring the 25% quota for women does not fall on all parties equally, The implications of these varied dynamics, for the potential of this quota to transform gender relations in local politics therefore remains to be seen.