Featured image courtesy president.gov.lk

On November 8 President Maithripala Sirisena called the irregularities around the Central Bank bond issue a “maha vinashaya” (a huge destruction) and said that those behind it must accept responsibility. He was speaking at a commemoration event for Maduluwawe Sobitha Thero, widely acknowledged as a driving force behind the citizen’s movement which brought Sirisena into power in 2015. A key promise made during election campaigns was to tackle ongoing and entrenched corruption.

In August 2016, the President himself, was implicated in a massive scandal. Company emails showed Sirisena, then a Cabinet Minister under the Rajapaksa regime, had along with aides demanded a political “donation” from Snowy Mountains Engineering Corporation (SMEC). At the time, the President’s Media Director promised a response would be forthcoming, and possibly, legal action. One year later, the story has faded from the headlines, and from people’s collective memories.

Three months later, in October 2016, Sirisena lashed out at independent commissions, and shortly after the Director General of the Commission to Investigate Allegations of Bribery and Corruption (CIABOC) Dilrukshi Dias Wickramasinghe resigned. Though there was no official reason given for her resignation, it was implicit that the move was a response to Sirisena’s comments. The move by the President drew much condemnation from civil society, as well as on social media.

A year later, the reception of the Director General’s office at the CIABOC is a hive of frenetic activity. Legal officers juggle ringing phones and stacks of cardboard files. These files are then ferried off along rabbit-warren corridors, to other departments. Each file represents a different case, and the Commission handles hundreds of files every day.

Complaints arrive at the CIABOC one of several ways – either through a letter addressed to the Chairman, the Director General, or to the Commission itself. The CIABOC also receives complaints from other government institutions, or voluntary organisations such as the Anti Corruption Front (ACF). Some of the complaints on bribes paid are anonymous, or use a pseudonym.

The Commission also has the power to begin investigations through its own volition (following a newspaper report, for instance). However, this power has never been used, as the CIABOC revealed in response to an RTI request, publicised at the recent relaunch of the Right to Information advocacy website, RTIWatch.lk on September 28.

Once a complaint has been received, the next step is for the Commission to decide whether or not there is enough material in the complaint to begin an investigation immediately. If so, the case is handed over to an Investigating Officer to begin. If not, the person making the complaint may be called in to provide further information. If the complaint is anonymously submitted, this is a further obstacle to overcome – the Commission then has to call in its legal officers to assess whether there is enough information to begin investigation.

In some instances, after all these steps, it will be found that the complaint cannot be investigated further, or that it can be taken forward after feedback from another Government authority. As of September 30, over 300 complaints are pending reports from other institutions. It is only after every possible step is taken to investigate that a file is considered “closed.”

Those complaints can be taken forward will see the drafting of indictments by the Legal Officers. There are just 30 Legal Officers for the entire Commission, and they are expected to draft detailed reports on each complaint. Upon final approval by first the Director General and then the Commission itself, the indictment is finally filed in court.

The reason for the buzz of activity outside the Director General’s office is now apparent.

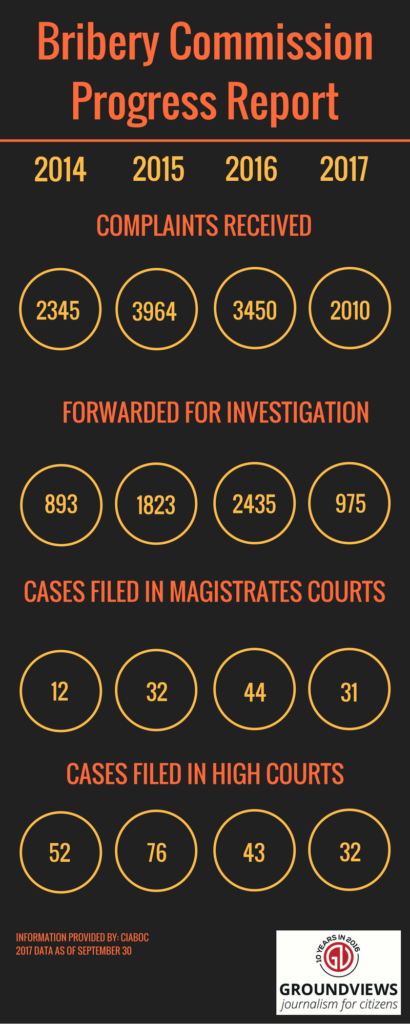

Groundviews was able to receive data on the total number of complaints, cases filed, and convictions over the past four years, courtesy a legal officer from the CIABOC, and created a number of infographics based on information received, in light of International Anti Corruption Day, which falls on December 9. Based on the information shared by the CIABOC, as of September 30, 2017 there were 2010 complaints received in total, of which 975 were forwarded for further investigation. The CIABOC also conducted 37 successful raids resulting in arrests.

Most of the cases investigated are for corruption, rather than for cases involving bribes.

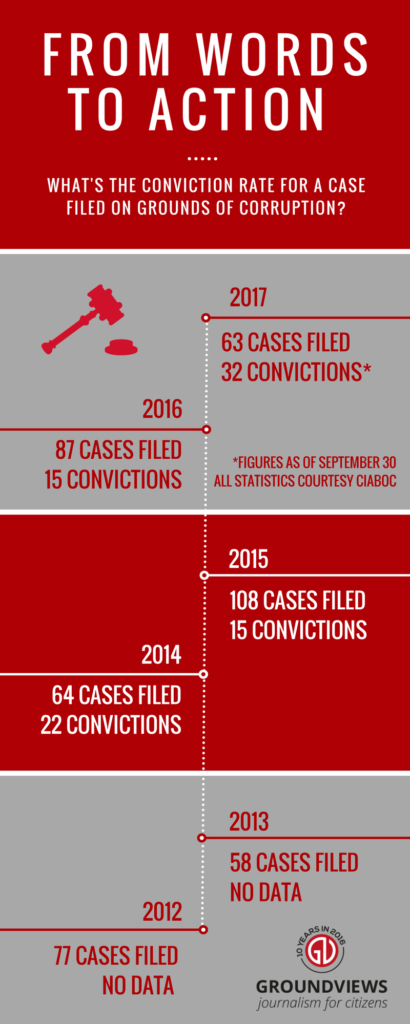

Only a fraction of the investigated cases end up in court. This year, for instance there were a total of 63 cases. Overall the CIABOC says that there are around 121 cases ongoing in the Magistrates Courts, and a further 289 cases in the High Courts.

32 cases were filed in the High Courts in 2017 – 30 of them bribery related. A further 31 were filed in the Magistrates Courts (19 of them related to corruption).

Despite all the obstacles in process, 2017 has seen more convictions compared to earlier years – 32 convictions in the Magistrates and High Courts. This is compared to just 14 convictions in both the Magistrate and High Courts in 2016.

It has to be noted that there has been progress made on investigating corruption in some high-profile cases, compared to the previous regime – most notable of which include Former Minister of Finance Ravi Karunanayake and former Central Bank Governor Arjuna Mahendran. Karunanayake stepped down from his post after allegations were made during his testimony to the Presidential Commission of Inquiry into the Bond issuance by Central Bank.

Former Minister of Justice, Law and Order and Buddha Sasana Affairs was also removed from his post by Sirisena, in part due to stonewalling cases of corruption. While this is laudable, the battle is far from over.

The activities of the CIABOC recently became a topic of discussion in Parliament, with both Government and Opposition MPs expressing dissatisfaction with the delay in taking action against corruption. For instance, MP Buddhika Pathirana said there had been no action taken with regards to two complaints made by him in 2015 and 2017, Chief Government Whip while JVP MP Bimal Rathnayake suggested setting up special courts to hear cases on corruption, in order to expedite the process.

When contacted, MP Ranjan Ramanayake said that he had heard from the Director General that they needed time to conduct proper investigations. However, Ramanayake said that there were clear issues especially when it came to accountability – for instance, former MP Sajin Vass Gunawardena was fined just Rs. 1000 for non-declaration of assets in the years 2011 and 2012, while former Director General, Telecommunications Regulatory Commission Anusha Palpita and former Presidential Secretary Lalith Weeratunge received a sentence of three years rigorous imprisonment (RI) and then were granted bail in the infamous “sil redi” case, which involved the misappropriation of Rs. 600 million of funds.

Beyond the points Ramanayake raised, there have also been questions around the Presidential Commission of Inquiry into the Central Bank bond issue, most recently because detailed information on phone and WhatsApp calls was leaked to the media. The subsequent protests on this score forced the Commission to release a statement noting that they had not tapped any MP’s phones in order to receive the call logs. An order was also reportedly sent out to arrest Former Defence Secretary Gotabhaya Rajapakse, for building a museum to his parents using public funds. President Sirisena blocked the arrest, claiming that the visit of a group of monks raising concerns around the order did not influence his decision. These incidents illustrate that high-level cases investigating corruption are led by party and political interests, rather than on the evidence presented.

The headlines keep coming. On October 11, Sri Lanka was implicated in a massive corruption scandal involving Airbus.

Regularly, news items surface of local government officials arrested for soliciting bribes, for the inclusion of a name in the voter register, to smooth the import of vehicle spare parts, or for a traffic offence. As cases pile up, the CIABOC appears to be struggling to keep up, with staff constraints and bureaucracy ensuring that cases proceed at a slow pace. Given these obstacles, it is laudable that the Commission has been making progress, slowly but surely. Over 1,000 complaints were concluded in 2017, 410 of them after investigation. A further 410 cases are currently being heard in the Magistrates and High Courts. Given more resources, the Commission could be empowered to do much to combat corruption. However, in the absence of political will to do so, the situation will remain as is – with an ever-growing pile of files.

Editor’s Note: Also read “Examining Facets of Corruption in Sri Lanka” and “The significance of Anika Wijesuriya’s evidence: What should we request from President Sirisena now?“