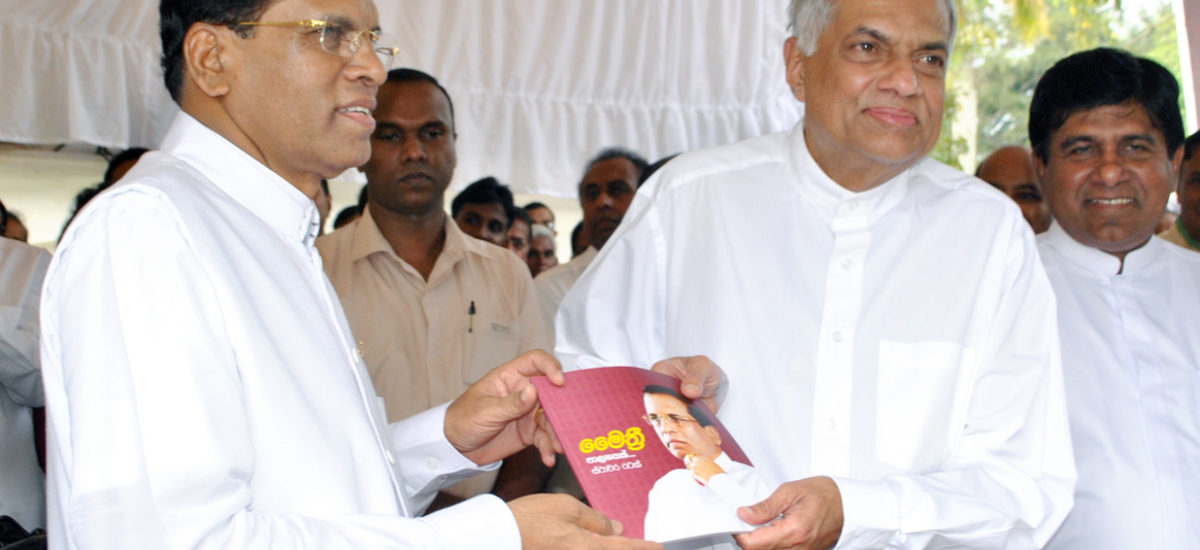

Groundviews is celebrating its tenth anniversary at a time when there is little else to celebrate in Sri Lanka. Particularly sad is the ways in which President Maithripala Sirisena and Prime Minister Ranil Wickremasinghe are ruining whatever little that remains in the political potential of their yahapalanaya (’good governance’) regime. President Sirisena is doing it with a little loyalty to the constituencies that enabled him to win the presidential election in January 2015. He has been going after the mirage of establishing his leadership over the SLFP, which fought tooth and nail to defeat him at the last presidential election. The Prime Minister is doing it by deploying a deadly combination of personal arrogance, managerial incompetence and school-boyish skills for trivialising crucial issues of governance.

Meanwhile, ever since the Sri Lankan voters toppled the Rajapaska regime January last year, the possibility of the autocratic, corrupt and unrepentant combination of Rajapaksa brothers defining again the path of the country’s politics as well as the terms of political discourse is now becoming real.

In parallel and certainly more seriously, less than two years in power, the dark side of the yahapalanaya regime is getting gradually institutionalised and also increasingly exposed.

Looking at Sri Lanka’s current politics with a definite sense of unease, I detect four disquieting trends in the country’s current politics.

The first is the regime’s unchecked alienation from its own constituencies. This process has been hastened by the continuing disregard that the government’s two leaders and their ministers – actual number of the latter is anybody’s guess – demonstrate towards the mandate of reform and good governance which the electorate gave them at the presidential and parliamentary elections, held last year. The shallowness of the regime’s commitment to its own promises can no longer be concealed.

The second is the lack of political direction for the regime which both the President and the Prime Minister have failed to provide. Judging by their regular public speeches, one can only conclude that these two gentlemen do not seem to have the political and intellectual capacity even to comprehend their own failures in power. Worst, they seem to be rejoicing over, and even proud of, their inability to be self-critical.

Third is the re-emergence of the defence establishment as a key and silent player in re-shaping and undermining some crucial public policy commitments which the yahapalanaya regime made last year. If the regime change last year re-calibrated the lopsided civil-military relations in Sri Lanka in favour of some measure of democratic equilibrium, that crucial good governance trend is now halted, largely, as it seems, at the behest of the presidential secretariat.

The fourth is the increasing possibility of the Rajapaksa brothers, backed by a remobilisation of Sinhalese nationalist constituencies within both the state and in society, pushing the regime to a state of paralysis and chaos. The yahapalanaya leadership does not show any capacity, or even willingness, to counter this threat.

Against this backdrop, I wish to discuss, in brief, two themes that can help us to analyse and respond to Sri Lanka’s emerging political crisis. The first is the fate of reformist regimes in the aftermath of authoritarian regimes. The second is the alternatives available to democratic and reformist constituencies.

‘Normalisation’

The regime change of 2015 occurred at a very crucial conjuncture Sri Lanka’s contemporary political change. It was the moment in which the UPFA regime headed by President Mahinda Rajapaksa, was ready to take Sri Lankan authoritarian politics into a new phase, making a transition from soft authoritarianism to hard authoritarianism. Soft authoritarianism refers to authoritarianism practiced by governments in power, within a general, albeit weakened, framework of democracy. It is usually confined to the authoritarian behaviour of government leaders and officials, without overthrowing the democratic foundations of the state. In short, it refers to regime authoritarianism.

Hard authoritarianism in contrast comes into being with the authoritarian transformation of the state. Soft authoritarian regimes can be dislodged from power and replaced by democratic, and electoral means. Hard authoritarianism of the state requires heavy political costs for its change – often violence, bloodbath and sometimes, political revolution. It is to the credit of all those democratic forces and the politically mature Sri Lankan electorate that they put a halt to such a fatal political transition to hard authoritarianism in our country. If he won a third term in January 2015, Mahinda Rajapaksa would have transformed Sri Lanka into South Asia’s Turkey, turning himself into another Tayyip Erdogan. A regime under such a ruler would have required for its replacement much more than an electoral challenge – really a protracted blood bath.

The real historical task before the yahapalanaya leadership, since January last year, has been to institutionalise the political change that pushed them into power and prevent any recurrence and return of authoritarian, soft or hard. This is precisely where the Sirisena-Wickremasinghe leadership has, in the final analysis, failed, and failed dismally. Recognizing, grudgingly though, their own failure, they seem to be all out now to enter into surreptitious alliances with the Rajapaksa forces. The halting and undermining of the inquiries and judicial processes in the very serious cases of human rights violations, war crimes and corruption has no other credible explanation. When the two power centres of the regime and their paid employees make mutual accusations against each other of indulging in the politics of deal making with the Rajapaksa camp, the real truth becomes easily visible: Both camps, obviously, are guilty of resorting to the politics of ‘deal making’ (deal demeema).

The latest episode is the one in which the Inspector General of Police is allegedly giving an undertaking, in the glare of TV cameras of the media, to the Minister of Law and Order that an accused of corruption, linked to the Rajapaksa camp, would not be arrested. The court jester mannerism of the IGP and the Minister’s totally unacceptable behaviour in that video, which have gone viral across social media in particular, tells us volumes about the degree of political, ethical and institutional degeneration into which the yahapalanaya regime has fallen. What makes the matters worse is the fact that this minister in question is a close confidante, a member of the inner circle, of Prime Minister Wickremasinghe. Perhaps, for this particular minister, kinship links sigh some Rajapaksa cohorts have greater salience than good governance.

When a regime which comes into power with a reformist agenda and fails to deliver on its promises, it then suffers a process which may be called ‘regime normalisation.’ A reformist regime becomes ‘normal’ when it begins to turn its back on the promises of democracy, human rights, and ethical governance and in turn becomes like the one it replaced. Regime normalization is a process that erases the distinction between the previous regime and the new one, because corruption, abuse of power, and human rights violations are the norm, rather than exception, in politics. Sri Lanka is not alone in this predicament. This has happened in many Asian countries in recent years, in Pakistan, Nepal, Bangladesh, Thailand, and Indonesia. Burma probably is on a slow path to ‘normalization.’ A serious theoretical analysis of this phenomenon requires another essay.

Democratic Defences

What options available for the democratic and reformist constituencies that have brought the yahapalanaya regime into power last year? The first answer to this question is simple: there is no point in maintaining any positive hope about a regime which now can show only its dark side. As they say it in India, the yahapalanaya regime has now crossed the Lakshmana Rekha of its ethicality and legitimacy through a series of actions and inactions that has drawn severe public criticism with little repentance from the government. The regime shows no capacity, will or intellectual preparedness to reform itself. It is sad that the government leaders, as President and Prime Minister often do, trivialise and dismiss public criticism, except when it serves their narrowly individual agendas.

If the recession of democracy is a regular and recurring reality in politics, is there any point in pinning our hopes on positive political change? My answer is ‘yes, there is,’ as long as our society has the capacity and will to re-build and reinforce its democratic defences. One extremely positive sign I notice amidst the sense of despair prevalent in Sri Lanka is the social resistance to, and the relentless exposure of, the regime misbehaviour. Some of the social media and the alternative press are channelling this critique in a direction that prevents the Rajapaksa camp from exploiting the failures of the yahapalanaya experiment. The fact that the Rajapaksa camp does not show any signs or even capacity to challenge the yahapalanaya regime through a democratic reform agenda paradoxically has a good side as well. It does not, and cannot, use the democratic aspirations of the people to prop up the Rajapaksa family’s bid to return.

Re-build, reinforce and sustain the Sri Lankan society’s democratic defences. That is the best strategy for us to see positive and more concrete changes in a post-yahapalanaya phase of Sri Lankan politics. Regimes come and go; but democratic defences should stay strong in order to protect the kind of political goals that are worth fighting for.