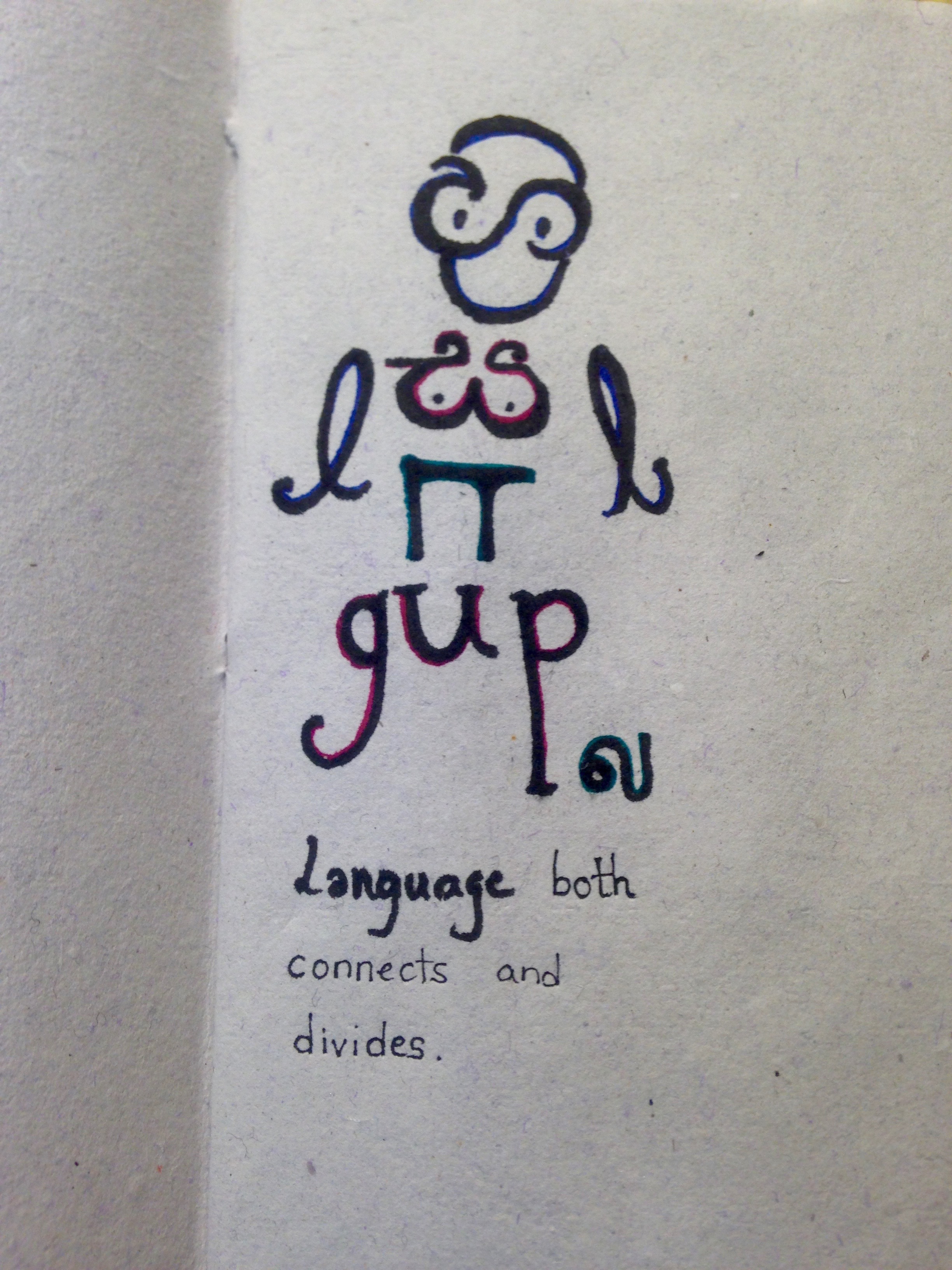

Language can simultaneously connect and divide, as Sri Lanka has learned to bitter effect in the past.

The divisiveness could be said to have begun with the Official Language Act of 1956, which saw Sinhala replace English as the official language, and Tamil being shunted aside. This stemmed mostly from the nationalist perspective that Sri Lankan Tamils had a disproportionate share of power in terms of educational opportunities and positions in civic administration.

This, in turn, led to the Tamils feeling alienated. Though Tamil was reintroduced as an official language in a legal amendment in 1987, the damage was already done.

This division has been identified as one of the root causes of Sri Lanka’s ethnic conflict.

Six years after the war ended, language continues to be a burning issue.

As Sunday (February 21) is International Mother Language Day, Groundviews features the work of artists and performers who have incorporated the issue of language, and Sri Lanka’s struggle with it, into their work.

Imaad is a writer, poet and musician who curates events like Kacha Kacha, which brings together performers in a variety of languages. It is quite normal for performances to segue between English, Sinhala and Tamil within the space of a short hour.

In 2014, Imaad wrote AntiPoem, which made him want to take a closer look at the Official Language Bill.

The result is a work-in-progress he initially called ‘1956’

As Imaad explained, the first, 9th, 5th and sixth words were collected in a spreadsheet, which were then fed into a Dadaist poem generator. The result – a series of phrases of four words each, which he then edited for coherence.

The process itself was painstaking and raised many conundrums.

It also revealed many interesting coincidences: not just the words that were eventually chosen, but also those that were left out:

Imaad went on to create a different poem using the words excluded by his method:

To sotto to Ponnambalam (A Paraphrase)

prescribe the Sinhala

the one of Ceylon

and transitory provision

made, presented by

S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike,

and Minister of

External Affairs.

2.49 P.M.

Before the Bill

just been the

Hon. Prime put down

Reading, I propose a

question propriety.

In my proposed Bill

violation of Article the

Constitution Council of 1946.

S.W.R.D. Bandara-

naike the appropriate

moment that question?

The Hon.

Prime a question,

to me, namely,

is the appropriate time to

raise Indeed, I

my mind to

and I of a more

to raise when

the Bill and placed

Table of this have

looked precedents

where the raised not

Standing Orders of but

in constitutional propriety

in Bill should present-

ed at all violation of

In my submission the

most and that is

am raising

was going to the Consti-

tution

“This work came about as I was coming to terms with being stronger in English than in Sinhala and Tamil, and observing how it affected my interactions with other people. Language does come into play, along with social class and privilege,” Imaad said. “I felt quite disconnected with my mother tongue. Given the conflict, we had to study in Sinhala medium as I was Muslim, and people were afraid to speak Tamil in public. So this conflict was something I understood very well.”

Imaad plans to continue the project, using a different method for each page of the Hansard.

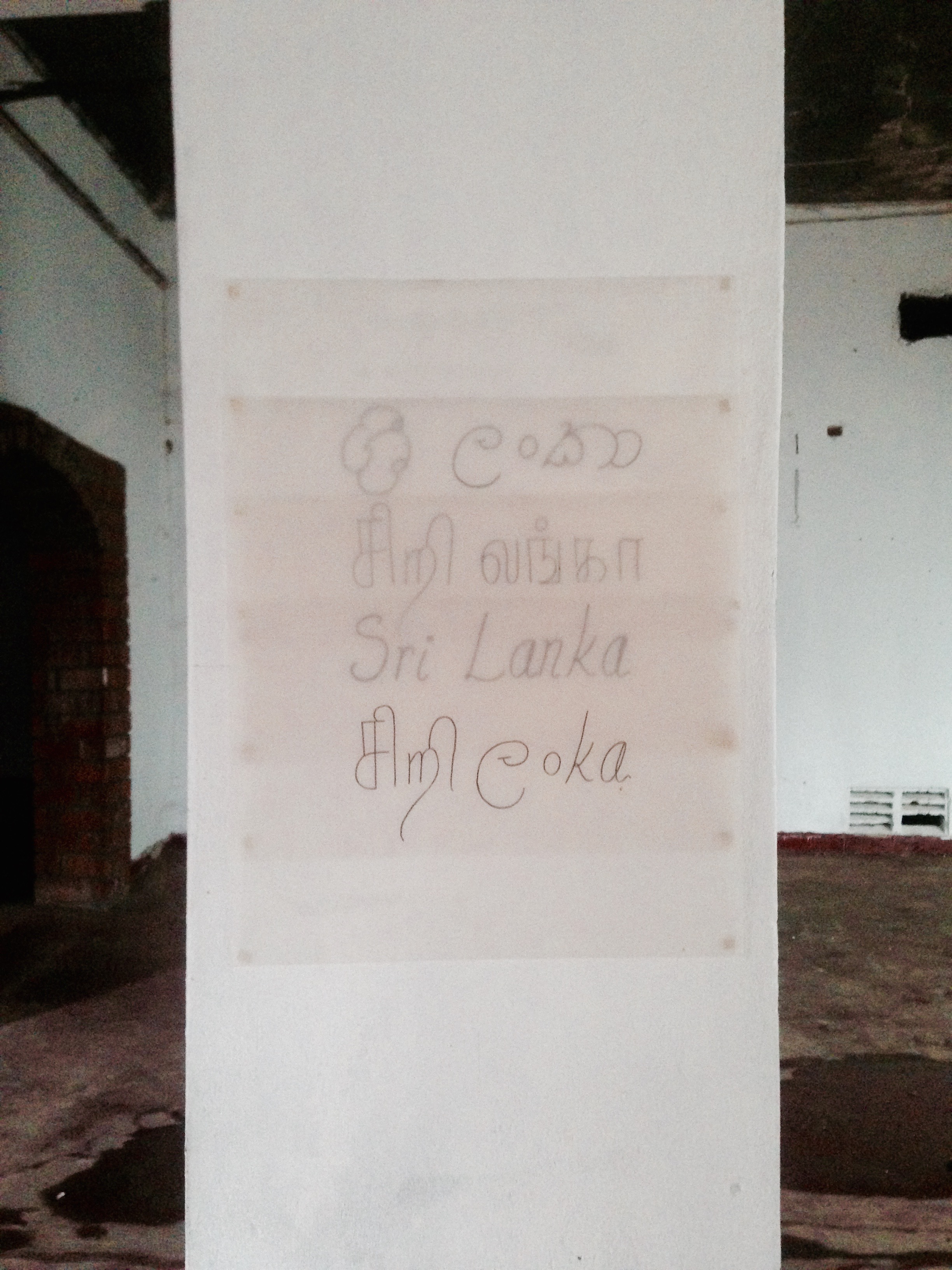

Pathum is a graphic designer with an interest in how culture shapes design, focusing on vernacular design in particular.

“I always loved letters, and everything about them,” Pathum explains about his motivation to be a typography designer.

Rather than simply focusing on creating aesthetically pleasing typography, however, Pathum decided to use his talent to try and solve the resentment generated by conflict through his project, Amma.

Amma is a hybrid font merging elements of Sinhala and Tamil script, in a way that is understandable to both communities. In the video, Pathum explains the process that went into creating his font:

His unique project, which is on github, attempts to solve the divisiveness created by conflict, and could be used on signboards and food packets in conflict-affected areas, he points out.

Amma drew much attention – Pathum was chosen as a speaker for designer showcase Pecha Kucha Colombo, as well as for the annual Typography Day.

KingSouth Krishan

Krishan Mahesan, (aka KingSouth Krishan) could be called a pioneer in the Tamil rap scene. Apart from his quickfire performance, though, he is also unique in that he has attempted to bridge language divides through his work.

In 2001, Krishan teamed up with Iraj to produce ‘J Town Story’ a hip hop song with conflict as its subject matter. The track featured Yaluwanan Wigneswaran and Infaas Noordeen.

Krishan has worked with musicians like Ashanthi and Randhir as well, with the idea of bringing people together through music.

The popular ‘Ran ran’ in particular saw all three languages being represented in one song.

“We bridged ethnicities by coming together to produce music. What we wanted to do is merge the Sinhalese and Tamil culture, through music,” Krishan explained – and it worked.

“The songs went commercial. Even though Sinhalese didn’t understand the music, they would sing along with the Tamil rap verses,” Krishan said. “Tamil people too started listening to Sinhala songs.”

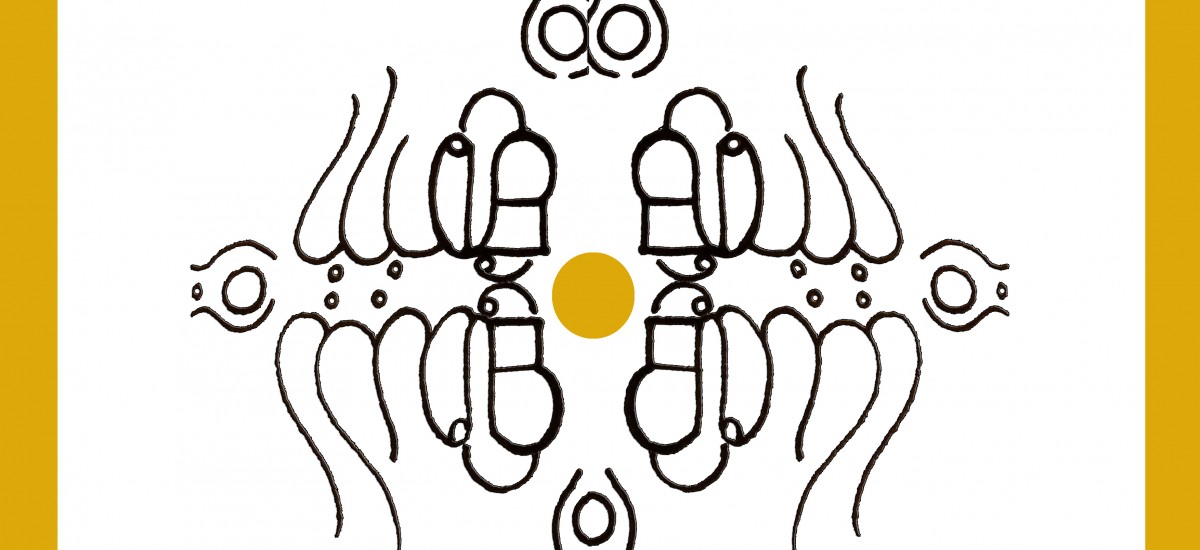

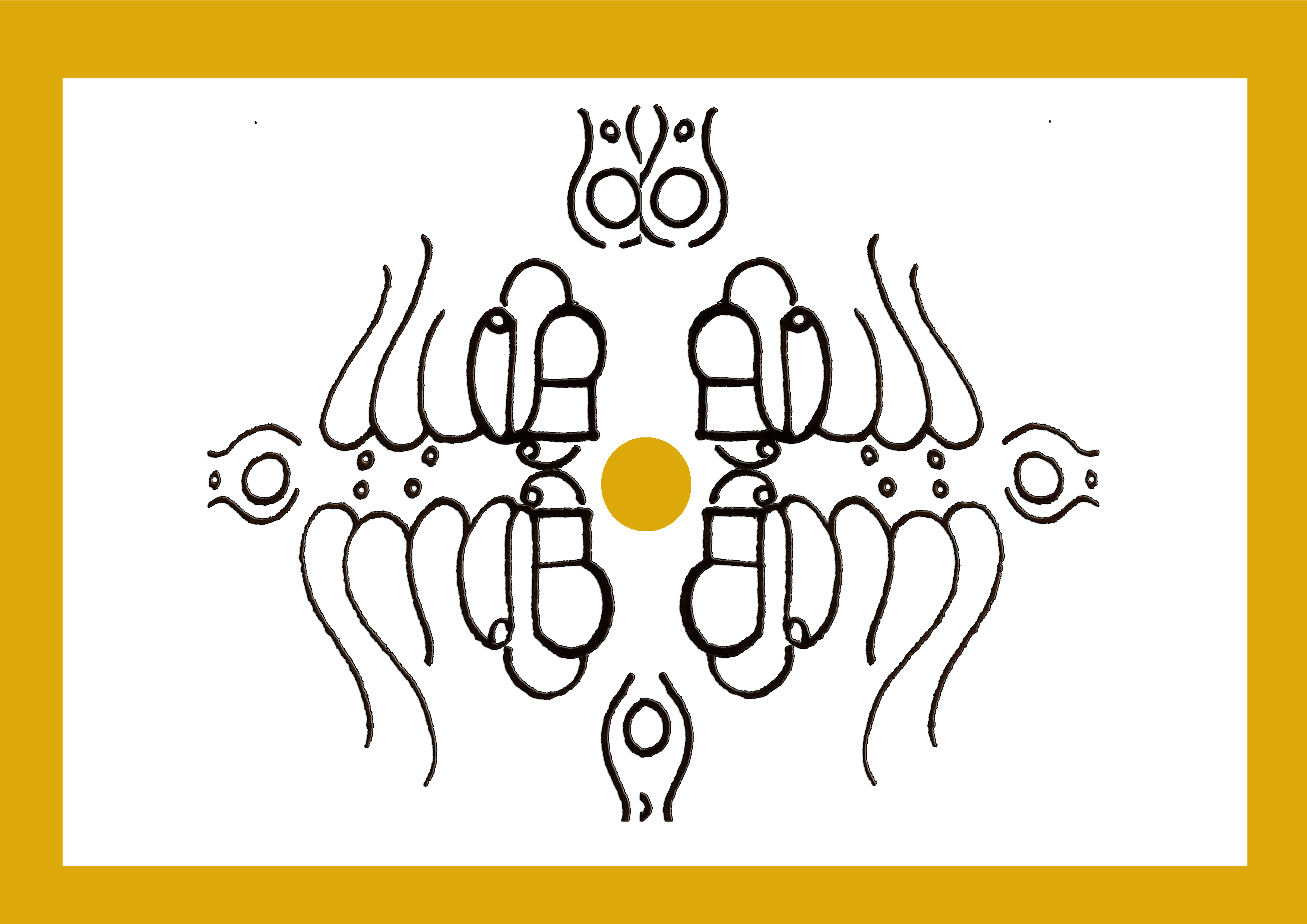

An interior design student and artist, much of Minal Naomi’s work explores themes of identity. She recently became fascinated with the double-edged sword that is language.

This exploration, which started out from doodles, has led to artwork displayed at the recently held Colomboscope, and has also formed an essential component of her final year project.

“My study of language stems from the exploration of my own identity, as a person of mixed ethnicity. I identify equally as Sinhalese, Tamil and Burgher. However it was interesting to me to note how people interacted with me on the issue of language – with most expecting me to be more conversant in, and identify more with, one language in particular. I tried to find the commonalities in both languages in the work that I do in order to communicate that language should be used as a tool to connect, not promote divisiveness.”

For the first time since 1949, this year the national anthem was sung in both Sinhala and Tamil. This was celebrated by some, but raised outcry from others, leading to lengthy debate on the history of the national anthem, and whether or not it should be sung in one language.

There is also the pervasive spread of slogans promoting the Sinhalese and their interests – which in itself are ominous signs of things to come.

It is an encouraging sign, however, that so many have come forward calling for unity, even in this unsettled environment.

If Sri Lanka is to avoid future conflict, there is a need to put aside the divisive thinking and insecurities that have led national discourse in the past. Whether this will actually be achieved, however, is yet to be seen.