Featured image courtesy vivalanka.com

“My wish for 2015: To be a free citizen of Sri Lanka, not just a servile subject!”

I shared those words one year ago on Twitter and Facebook through a simple web meme. At the time, it was very much an aspiration, as we Lankans were still living under a regime that harboured monarchic delusions and had little regard for our rights as citizens.

And a week later, at Sri Lanka’s seventh presidential election, we citizens sent that regime home. Contrary to some assertions, it was an entirely a home-grown, non-violent and democratic process. An impressive 81.52% of registered voters (or 12.26 million persons) took part in choosing our next head of state and head of government: Maithripala Sirisena.

It was also Sri Lanka’s first national level election where smartphones and social media played a key role and probably made a difference in the outcome. During the weeks running up to 8 January 2015, hundreds of thousands of Lankans from all walks of life used social media to vent their frustrations, lampoon politicians, demand clarity on election manifestos, or simply share hopes for a better future.

As I documented shortly afterwards, most of us were not supporting any political party or candidate. We were just fed up with nearly a decade of mega-corruption, nepotism and malgovernance. Our scattered and disjointed protests – both online and offline – added up to just enough momentum to defeat the strongman Mahinda Rajapaksa. Just weeks earlier, he had appeared totally invincible.

Thus began the era of yaha-palanaya or good governance.

One Year of Breathing Easily

So did we the citizens live happily ever after?

No, that only happens in Disney movies and sycophantic Lankan media. In real life, democracy is a work in progress and good governance, an arduous journey.

One year on, Sirisena — and his motley collection of opposition parties – came together under the banner of enhancing governance and cleaning up politics – have fallen short on both counts.

Betrayal? Not necessarily. Our expectations were too high to begin with, and so looking back at the first year of yaha-palanaya, we can find many shortcomings and letdowns. Notwithstanding these, the past year has been a major improvement over the Decade of Darkness that preceded it.

In other words, the yaha-palanaya glass is only half (or quarter?) full; it’s easy for critics to focus on the remaining emptiness. But let’s not forget that there was no glass at all earlier – it had been smashed up by the Rajapaksas.

To the lasting credit of Sirisena and his Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe, the new government that took over on 9 January 2015 quickly and resolutely ended the militaristic repression and high levels of intolerance that characterised the Rajapaksa regime (especially after 2010). That made a huge difference.

No longer are we treated as disenfranchised subjects of an authoritarian ruler. No longer do we – journalists, activists or ordinary citizens — live in constant fear of violent reprisals for simply asking some inconvenient questions in the public interest. No longer must we take protective cover behind pseudonyms, satire or innuendo to criticise key figures or actions of the government.

And no longer do we hesitate before ridiculing and lampooning the top political leadership. I’ve been doing so for much of the year in public using social media — and never once been threatened.

We have not had such freedom of expression for decades. Even the seemingly liberal Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunge used to hit back at persistent critics, especially during her second term. Her successor took it to unprecedented depths.

Lofty ideals

Ok, so we can ‘bark’ more freely now — but does it change what really matters in democratic governance? That remains to be seen.

It is not yet clear how much — and how deeply – the promised political and democratic reforms will be institutionalised. The 100 Day programme was ill-conceived and over-ambitious. There is a big gap between campaign hype and governance realities, as the new government quickly realised. We citizens were reminded of the well know Lankan folk tale of how a supplier claimed and actually made jaggery (a sugar substitute) for his king…

Lofty ideals like judicial independence, media freedom and open government have been bandied around without adequate policy cohesion or even conceptual clarity. For example, it took a whole year to draft a law guaranteeing citizens’ right to information (and that too, amidst much opposition by sections of the bureaucracy).

But at least we have embarked on the right path by adopting the 19th Amendment to the Constitution that created independent Commissions. We are also having public discussions on what more needs to be done – including reconciliation and a new Constitution.

To be frank, yaha-palanaya’s meandering progress and its leaders’ rising expediency have repeatedly disappointed me during the past 12 months. But as I have tweeted, that is not a reason for looking back.

Indeed, voting in two key elections during 2015 was the easy part. We now have to be vigilant and stay engaged with the government to ensure that our politicians actually walk their talk. (Given half a chance, they won’t.)

Here, we can strategically use social media among other advocacy methods and tools.

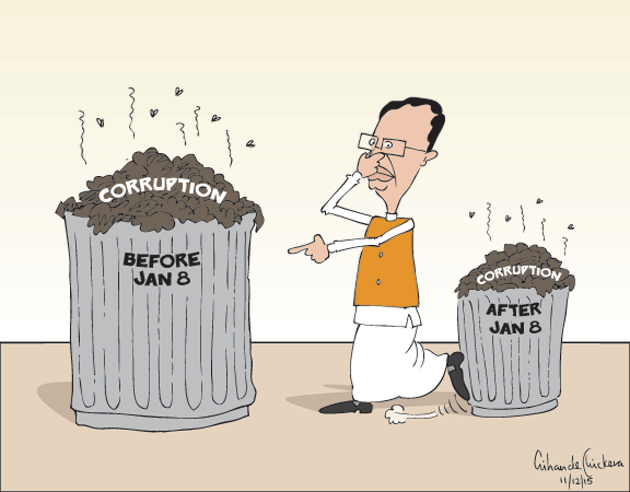

Gihan de Chickera cartoon, published in Daily Mirror, December 11

Presidential Aloofness?

Maithripala Sirisena’s election manifesto of December 2014 pledged to “enforce a media development policy for managing developing communication technology and the expansion of social media for the good of society”. Shortly after being elected, he acknowledged the substantial support he received via social media during his campaign (which was voluntary and spontaneous, not orchestrated by anyone).

Yet, if Sirisena was the first Lankan politician to have derived such electoral gains, he has since done little to engage voters and other citizens using the same social media.

Like other politicians in Sri Lanka, he uses key social media platforms like Facebook and Twitter to simply disseminate his speeches, messages and photos. His official website has no space for citizens to comment. That is old school broadcasting, not engaging.

True, Sirisena’s verified social media accounts have steadily increased in the number of fans/followers during the year – boosted in part by the benefit of incumbency. But he and his media team never join the conversations that unfold in social media, even when the mood is far from adversarial.

This apparent aloofness, and the fact that he has not done a single Twitter/Facebook Q&A session before or after the election, detracts from his image as a consultative political leader. Then again, that seems to be his communications style, to make a key policy statement once every few months, admirably with none of the pomp and bravado of his predecessor.

The interregnums have been characterised by long spells of silence, or filled with mundane postings on social media with hardly any policy or news value. This could well be due to the Presidential Media Division being stuck in 20th century’s media mindset.

Take for example, the presidential silence that preceded Sirisena’s televised address to the nation on 14 July 2015 where he clarified matters and tried to diffuse tension arisen over Mahinda Rajapaksa being given SLFP nomination for the Parliamentary Election.

As I wrote at the time in a commentary titled ‘The Price of Silence in the Social Media Age’, “If a week is a long time in politics, 10 days is close to an eon in today’s information society driven by 24/7 broadcast news and social media. An issue can evolve fast, and a person can get judged and written off in half that time.

“For sure, there is a time to keep silence, and a time to speak – and the President must have had some good reasons keep mum. But in this instance, he [Sirisena] paid a heavy price for it: he was questioned, ridiculed and maligned by many of us who had heartily cheered him only six months ago.”

I argued at the time that Sri Lanka’s democratic recovery simply could not afford such uncertainty and distraction created by Zen-like long pauses – they don’t sit well with impatient citizen expectations of today. This is not 1977 when President JR could say nothing in public for months and get away with it.

No Compassion for Maithri?

That does not mean we want a presidential comment on every news development on a regular basis. Moralistic posturing may work with a live audience in rural Sri Lanka, but as Sirisena and team discovered with his December 27 condemnation of the Enrique Iglesias Colombo concert, a local speech can quickly go global in the social media age.

As if that was not enough, he made a second blunder of attacking those who contested his point of view, evoking memories the utter intolerance under the Rajapaksas. Should he insist on continuing this self-righteous and pontificating path, Maithri won’t get any maithri (compassion) from freedom loving citizens…

On the whole, I would far prefer to see a more engaged (yet far less preachy!) presidency. It would be great to have our First Citizen using mainstream media as well as new media platforms to have regular conversations with the rest of us citizens on matters of public interest. A growing number of modern democratic rulers prefer informal citizen engagement without protocol or pomposity. President Sirisena is not yet among them.

One fear on his part, I suspect, is the lack of control in social media engagement. Anyone from anywhere can pose a question during a Twitter or Facebook Q&A session – and not always using their real identity. Politicians like Mahinda Rajapaksa and Champika Ranawaka periodically take that chance. Sure, they deftly ignore tricky questions posed by the likes of myself, but at least they engage selectively. Sirisena is missing in this conversational space.

When to say nothing

Of course, there are certain times when not reacting at all is the best response, e.g. when situations can become public relations disasters. Here too, Sirisena & Co. have yet to learn their lessons.

A case in point was when the presidential offspring Daham Sirisena accompanied his father to the UN General Assembly in New York last September and occupied one of six seats allocated to Sri Lanka in the main hall (thus edging out Sri Lanka’s Permanent Representative to the UN, who had every business to be there).

Splashing photos of that occasion was ill-advised. Then someone in the team made matters worse by trying to digitally edit out the young man.

Lankan social media erupted with charges of nepotism and misdemeanour. Soon afterwards, Daham scored an own-goal by trying to defend it all in his own Facebook, reminding us definitions of nepotism in the process. Bad move.

A diehard supporter might ask: was that such a big deal when Rajapaksa used to regularly take planeloads of family members and cronies around the world at colossal expense of public funds? Yes, it was — because the yaha-palana president is held to a much higher standard. Get used to it.

Commenting at the time, I wrote: “Optics or appearances do matter. They are especially important in this social media age when every action of the government and its top leadership is closely monitored and commented upon by many citizens.”

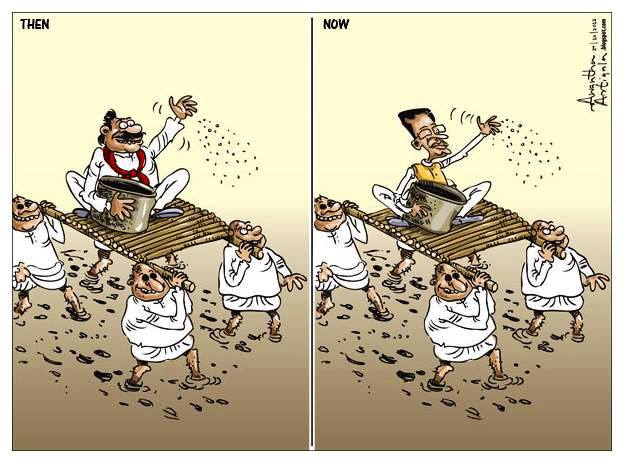

Spot the difference! Cartoon courtesy Awantha Artigala

Sirisena’s Choices

By end 2014, when Sirisena rode the popular and digital wave to high office, a quarter of Lankans were regularly using the Internet. The technology is actually casting a wider shadow on Lankan society beyond the direct users. Becoming head of state in such a society naturally places Sirisena under much greater scrutiny than any previous leader. He still can turn this challenge into an opportunity.

For that, he must first shed his perpetual siege mentality. We netizens are not out to topple him (oh, we sure like to kick him around irreverently, but hey, that’s our birthright!). On more than one occasion, he has publicly wondered if resistance to him is due to him “not hailing from an aristocratic family”.

In fact, Sirisena’s humble origins and grassroots level political experiences were clear electoral advantages one year ago. But now as elected leader of an open society, he will be watched, criticised and judged, sometimes even unfairly. That has nothing to do with his origins. Welcome to the Global Glasshouse!

If President Sirisena is pragmatic, he must now come to terms with being critiqued as no Lankan leader has ever been. And if he is also visionary, he can take advantage of today’s digital realities to become the most consultative head of state we have ever had.

After a year of hesitation and some mistakes, will he choose the path of true citizen engagement? We can only hope so – for his sake, and ours.

[Full disclosure: In early November 2015, I gave a talk on social media challenges and opportunities to the staff of Presidential Media Division, and then engaged them in a lively Q&A. Such an interaction was unimaginable under the previous regime.]

Science writer Nalaka Gunawardene explores the nexus between new media, society and governance. Tweeting from @NalakaG, he was among Sri Lanka’s top 10 most influential social media voices during both Presidential and Parliamentary elections in 2015.