The One-Hundred-Day Programme of President Maithripala Sirisena (MS) was launched last week with three good speeches, one of two promises largely kept and the third postponed, hopefully to be fulfilled sooner rather than later.

President Sirisena made three good speeches in the last seven days, the first at his swearing-in ceremony, the second in Kandy and the third when his Cabinet of ministers was sworn in. His continued emphasis on the principles of good governance, uncompromising opposition to corruption and to the cause of national unity is indeed heartening.

Sirisena promised to accomplish two major political goals in the first week of his new administration. One was the formation of an “all-party” Cabinet with UNP’s Ranil Wickremesinghe as Prime Minister. The other was the appointment of a national advisory council drawn from different poltical parties in parliament and representatives of “citizen groups.” The first was partially accomplished on Monday January 12th. Twenty-seven cabinet ministers, ten minsters of state and nine deputy ministers were appointed. It is not clear what the real distinction between the last two categories is but the title “Minister of State” sounds grander.

Twenty of the Cabinet ministers were drawn from the ranks of the UNP and the remaining seven including Sirisena himself represent seven other parties including the SLFP. The Tamil National Alliance (TNA) and the JVP did not join the Cabinet. This would doubtless have been a disappointment for Sirisena who wants to project himself as the leader that brings the nation together.

Sirisena’s manifesto promised that the “number, composition and nature of the Cabinet would be determined on a scientific basis” (p.14). Sirisena is committed to limiting the number of Cabinet ministers to 30. The “science” behind this number is not clear. But we do know that it is about half the size of the Rajapaksa cabinet that will help save some tax rupees.

The allocation of functions to the various ministries appears to be a little more “scientific” than in the last Rajapaksa administration which, on the one hand, had a large number of redundant ministries with little or nothing to do and, on the other, had three super-ministries, Finance, Defense and Urban Development and Economic Development, that concentrated power and resources in the hands of Rajapaksa and his siblings that held those offices. However, Sirisena’s Cabinet also has some odd combination of functions. For example Highways is combined with Investment Promotion. Estate Infrastructure Development is a ministry that perhaps is politically expedient to create but has little economic and functional rationality. Samurdhi, which is essentially a social welfare programme, is separated from the Ministry of Social Services and Welfare and attached to Housing.

Divided Sri Lanka?

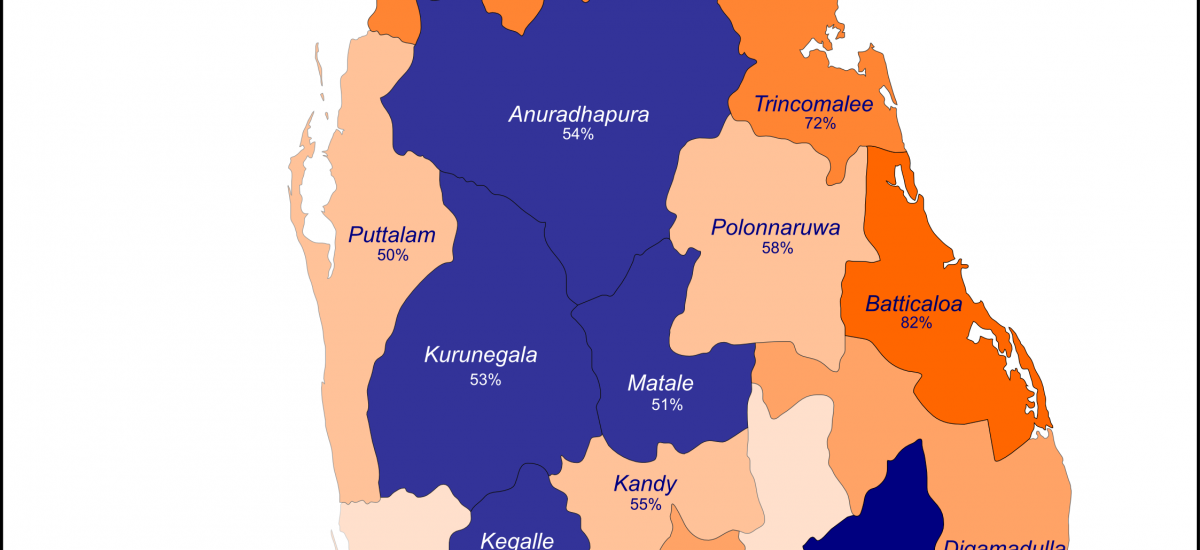

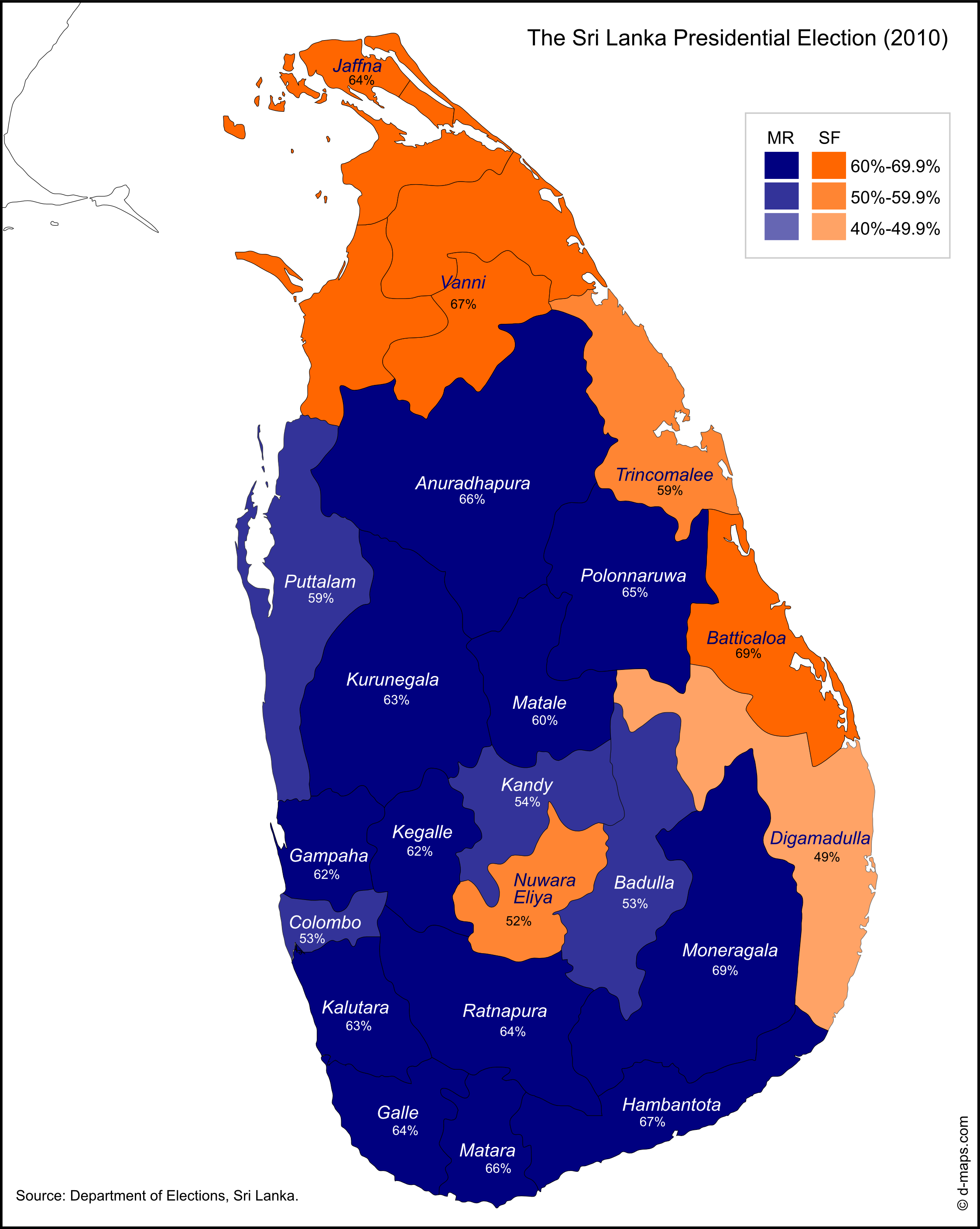

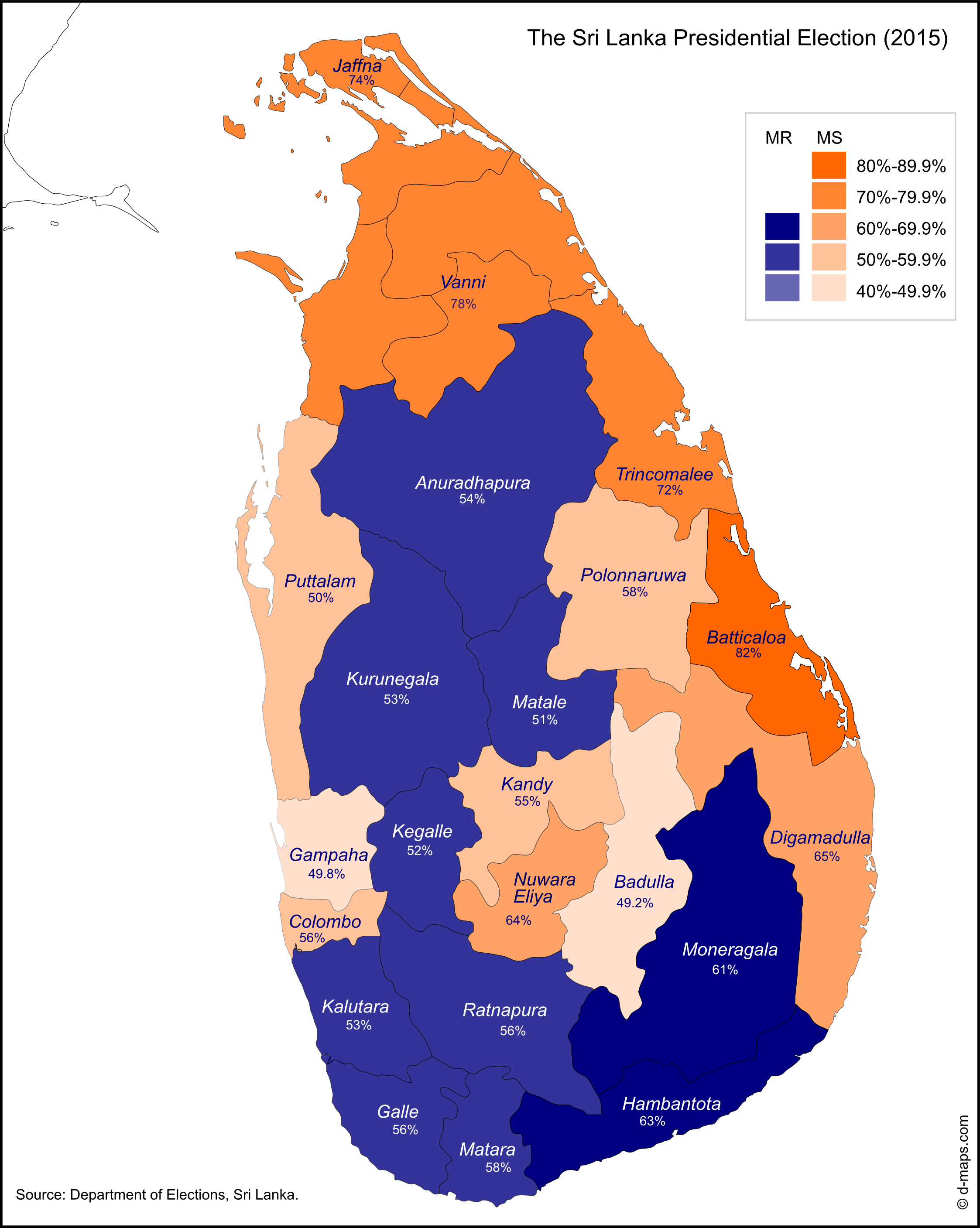

Some of Sirisena’s critics, especially those JHU leaders who have remained outside the Sirisena coalition, have questioned his right to represent the Sinhala majority who constitute 75% of the population. President Mahinda Rajapaksa in his post-poll address to his supporters at his Medamulana residence also deviously posed the same question and suggested that it is the non-Sinhala citizens that had elected Sirisena as president. Simplistic and inaccurate maps published widely showing the districts of the north, east, the central highlands and the Colombo district as Sirisena territory and the rest as MR territory have given some credence to this otherwise spurious argument. The facts indicate otherwise.

The national electorate consisted of 75% Sinhalese, 12% Sri Lanka Tamils, 4% Up-country Tamils and 9% Muslims. The “minorities” or the non-Sinhala segment that voted (2.6 million or 22% of the valid votes cast) split roughly 80% for MS and 20% for MR. The Sinhalese majority vote was about 10.6m. It split 5.5m (52%) in favor of MR and 5.1m. (48%) in favour of MS. The latter split does not constitute a plurality either way. However, as the two maps accompanying this essay show MS had made huge gains in the Sinhala majority rural districts in 2015 as compared to Fonseka in 2010. On average, the Sinhala voter swing against MR was about 10 percentage points.

The result can be interpreted in many ways. MS certainly would not have won without the overwhelming support of the “minorities”. But that does not make him a president representing only minority interests because he polled a very respectable 48% of the Sinhala vote. If the most pressing need is national reconciliation after a three-decade-old civil war, Sirisena’s mandate is the best to start that process because he has the support of all communities including nearly half of the Sinhala segment of the national voter base.

The above said, it is our contention that the more we refrain from identifying the Sri Lankan electorate in terms of its different ethnic groups the better it would be if we are serious about the promised attempt to create national unity and a more inclusive Sri Lanka in the foreseeable future. We would rather characterize those who voted for President Sirisena as Sri Lankans who desired a change in our political culture. To segregate them into the different ethnic groups, in our opinion, would be to devalue Sirisena’s victory. Until our inter-ethnic relations deteriorated precipitously especially in the post- 1970s, our political parties were not divided or identified on ethnic lines. All our major political parties consisted of all Sri Lankans who form our social mosaic. It is true that the Federal Party was made up of Tamil members but it had not yet become the Tamil United Front (TUF) or the Tamil United Liberation Front(TULF) until the 1970s. There were Muslim candidates in all of our political parties until the late M.H. M. Ashraff, much against the thinking of most sensible citizens, inaugurated the Sri Lanka Muslim Congress (SLMC) as a political party having established the SLMC as a political formation in 1981. Earlier in 1977, Ashraff and certain other Muslims formed the Muslim United Liberation Front in 1977 which collaborated with the TULF in that year.

Poltical Realignment

Ranil Wickremesinghe is struggling to ensure that he has the support of a minimum 113 members in a Parliament of 225. Having secured the support of over 25 UPFA government members in the last several weeks he was yet short of about one dozen by the beginning of last week. He is likely to reach the target before Parliament reconvenes later this week. However, the poltical realignments that are taking place both in Colombo at the national level as well as at the provincial government and local government level make for a great deal of confusion.

Wickremesinghe’s UNP has a majority in the Cabinet. But his position as leader of the UNP is much weaker in Parliament and more generally in the country. The 47% that Rajapaksa secured in the presidential election is largely hard core SLFP. That is discounting the minority of SLFP voters that deserted Rajapaksa on January 8th to vote for Sirisena. It is reasonable thus to assume that the SLFP today has a firm 35% base vote nationally and its share would be in the lower to mid 40s in the predominantly “Sinhalese-Buddhist” areas. The evidence that is available from recent opinion polls and elections including the presidential election held this month suggest that the UNP base vote is smaller, perhaps no more than 25% to 30% in the “Sinhalese-Buddhist” rural areas and suburbs and a littler higher in the 35% to 40% range in the Colombo district and a few other main towns outside.

The Sirisena vote would have been largely UNP. However, it also includes, besides the SLFP voters that deserted Rajapaksa, a small percentage of JVP and JHU voters plus the Tamil and Muslim voters who will likely vote for their ethnic parties in a parliamentary election. In such a context, Rajapaksa’s decision to handover the leadership of the SLFP to Sirisena makes the situation for the UNP even more difficult because now, in theory at least, there is a united SLFP in Parliament owing allegiance to Sirisena and they could claim a majority.

The unification of the SLFP also has significant but unpredictable implications for the next parliamentary elections that are due soon after April this year. Will the UNP and SLFP contest each other? What will be the stand of Sirisena who currently symbolizes national unity as head of a multi-party coalition? In the current volatile poltical situation it is hard to predict what would happen in the coming few weeks, let alone in the coming four to six months.

There is also an upside to this confused state of politics in the South. That is because the next parliamentary election is likely to be contested on certain significant political issues which will determine whether or not Sri Lanka marches into the future as a more inclusive democratic society. These issues include primarily, good governance, social justice and national unity, also known as “majority-minority” relations.

Sirisena’s Manifesto

Sirisena’s presidential election manifesto “A Compassionate Maithri Governance, – A Stable Country,” written as a common manifesto of Sirisena and the UNP-led coalition of parties addresses all three issues. The manifesto was presented as a long-term programme for a new government of national unity to be elected when fresh parliamentary elections are called.

In our view, the proposals in the manifesto are broadly good for the country. The UNP led coalition formulated it with the approval of Sirisena. Sirisena based his campaign on the foundation of this manifesto and won. Thus the manifesto has common ownership. Now Sirisena is to assume the leadership of the SLFP. It follows that both the major parties UNP and SLFP now subscribe to the same vision and set of policies. That means even if the two parties put forward candidates in the next general election to compete against each other it cannot be on the basis of different or alternative sets of policies. What then would really matter to the voters is the quality of the candidate and his/her suitability to represent them in Parliament and govern the country. In our view this is a positive development with the potential to produce a better quality Member of Parliament.

The One-Hundred-Day Programme promises to abolish the district-wide preferential voting system that favours candidates and parties with greater material resources and to replace it with the single member constituency system. The latter system gives candidates with modest means a reasonable chance to win a seat. Such a scenario hopefully would encourage candidates of better (human) quality to come forward to contest the forthcoming parliamentary election, a consummation devoutly to be wished, given the lack of basic decency that we noticed in a majority of the members of our Parliament in the last 10 years.

By S.W.R. de A. Samarasinghe and Tissa Jayatilaka