On the night of 8 January 2015, shortly after voting ended in Sri Lanka’s seventh presidential election, the streets of Colombo and suburbs were unusually calm. There was no curfew, but people stayed indoors and watched results unfold on television.

In contrast, the country’s social media was on fire. On Facebook, Twitter, popular blogs and elsewhere, Lankans were discussing and debating the election outcome and likely scenarios. Parallel to this, plenty of bilateral chats flowed through mobile messaging apps like WhatsApp ad Viber.

It was a long night for political players and spectators alike.

The frenzy intensified on the Day After. When the incumbent President – who had looked invincible just days earlier –conceded defeat even before all results were announced, Lankan cyberspace went into overdrive.

By mid-day, the Elections Commissioner announced the vote tally and the clear winner: Maithripala Sirisena, who polled 51.28% of votes. But as we now hear, there was much intrigue and drama during the election night. Let’s hope full details would soon emerge…

Right now, what matters is that the majority choice of 12,264,377 citizens has prevailed. Equally impressive is the fact that 81.52% of registered voters took part in choosing the next head of state – the highest ever at such an election.

That outcome was no fluke. It was the product of various factors that shaped public perceptions and opinions during the highly contentious election campaign period. The usual dynamics of political ideologies, money politics and clan rivalries played their part. Additionally, the information society dimension was prominent this time around — thanks to 25 years of mobile telephony and nearly 20 years of commercial Internet connectivity in Sri Lanka.

Here is what we do know. During weeks preceding the election, hundreds of thousands of Lankans from all walks of life used social media to vent their frustrations, lampoon politicians, demand clarity on election manifestos, or simply share hopes for a better future.

Beyond this, we have more questions than answers.

Did inter-personal communications and myriads of open, public conversations raise the level of public awareness of key political and policy issues relevant to this election? How much of this citizen awakening can be attributed to the fast spread of smartphones and broadband?

More important, could such fleeting communications really have influenced how people voted? Even if so, did cyber-savvy Lankans – who now make up a quarter of the total population – play a decisive role in the peaceful regime change?

Online, Offline

Such questions should be debated for weeks to come, and hopefully inspire rigorous academic study. For now, in the immediate aftermath, I can discern some broad trends. (Disclosure: I was no detached observer and was actively engaged in some of these processes.)

- Social media platforms, typically used for everyday chatter or digital content swapping, provided a vital space for opinion leaders such as activists, artistes, university dons and public intellectuals to network, collaborate, and disseminate political information.

- Easy-to-use digital tools – especially smartphones, coupled with some of the world’s cheapest call charges and data transfer costs – allowed citizens to engage in many public conversations on burning issues like racial harmony, militarization, large scale corruption, declining rule of law, lack of media freedom and state of the economy.

- Orthodoxy, sycophancy and gross misinformation in sections of the mainstream media were countered by bloggers, tweeps and other social media users. Such counterpoints were sometimes biased or bombastic, but on the whole they made our media experiences more pluralistic.

- Many social media interactions used the common hashtag #PresPollSL, enabling easy aggregating which, in turn, enhanced the breadth and diversity of interactions. In the aftermath, it also helps in the digital archiving for trend analysis.

- The clear nexus between the mainstream media and political campaigns – which paid hundreds of millions of rupees to buy media space or time – dented public trust in conventional news sources. Part of that trust deficit was bridged by online content.

- While mainstream and web-based media both covered the same news of political speeches, crossovers and election related violence, there was a marked difference in commentary and opinion. The Lankan blogosphere accommodated a much wider range of opinions and nurtured infinitely more discussion. I found some of the most cogent opinions and analysis online, and not in newspapers. (Some local language bloggers now command larger readerships than certain well-established newspapers.)

- Many social media interactions went beyond text. Politically charged citizens generated or shared ‘web memes’ and viral videos in larger numbers and volumes than at any previous elections. Ubiquitous mobile phones helped capture gaffes in political speeches and blatant violations of election laws. Lankan wit, sarcasm and satirical talent were evident in full force. Significantly, these irreverent smart mobs had no sacred cows; they spared no one.

- Bright and mischievous ideas, hastily executed, were shared widely in social media. Such memes often trumped the more sleek and sophisticated campaign materials produced by advertising agencies or PR companies. This questions the value-for-money proposition of high cost marketing and PR professionals in political campaigning.

- Imaginative civil society and advocacy groups, with better access to skills and resources, tapped into other digital tools. Resulting products like infographics, word-clouds (e.g. visualizing manifestos) and interactive maps (e.g. geo-referencing election violence) all enriched conversations.

Most of these trends were not purely digital or entirely web-based. In fact, it was the confluence of various online and offline factors that amplified social media’s outreach – and societal influence – beyond those directly using them.

Online campaigning?

The real game-changer has been the spread of smartphones — an estimated 3 million are being used in Sri Lanka (and rising), all capable of web browsing from anywhere with mobile signals. Some users of these mass digital tools are ‘multipliers’ with various online and/or offline audiences of their own.

Cyber sceptics who insist that new media reach is limited to cities or English language speakers miss out on such extended shadows, called penumbra in eclipses.

“Views on the ‘bookie’ are far removed from those of our majority rural people,” claimed one sceptic a few days ago (‘bookie’ being a slightly derogatory Sinhala term for Facebook).

He maybe right – but only up to a point. In reality, the urban-rural information divide in Sri Lanka is not as sharp as many believe. Information and communications technologies (ICTs) are no longer the exclusive domain of a privileged class. Language barrier in the digital realm has also been reduced by new apps and other recent developments.

How well did political parties relate to these new and complex digital realities? Did candidates find a good mix and balance of these new tools alongside more traditional ones such as public rallies, displays and paid advertising on print and broadcast media? Researching these questions would give us an idea how close we are to a digital democracy.

“This election saw an unprecedented use of social media in Sri Lanka,” says Ajith Perakum Jayasingha (@ajithperakum), a leading blogger, and political commentator. “Over 80% of our youth is computer literate – many have smartphones and regularly log in to social media. Political content they absorb from online sources spreads fast to (offline) communities in villages.”

Ajith argues that this was also the Rajapaksa campaign’s blind spot, probably based on the notion that most rural people are unreachable via such media. Instead, the incumbent’s election propaganda efforts were concentrated on conventional media and outdoor campaigning, he says. In that process, there were gross abuses of state controlled newspapers, radio and television.

Media over-exposure of the incumbent certainly happened, but the campaign had a strong online presence as well. As found in an investigation by Groundviews, the Rajapaksa campaign seemed to have invested substantial skills and resources in social media outreach.

Groundviews noted in mid December 2014, “What we see here is a revealing glimpse into a Twitter network managed by the President’s election campaign, or allied groups under contract, to generate and disseminate content in favour of the incumbent.”

They added: “Based on a cursory analysis of these Twitter accounts alone (keeping in mind the President’s social media reach extends to a panoply of Facebook accounts, in addition to YouTube and even Instagram), it is extremely clear incumbent’s re-election campaign on web based social media is, by a long shot, far more sophisticated and carefully engineered than anything the Maithripala Sirisena coalition has, to date, even thought of.”

The Rajapaksa campaign reportedly engaged the services of Arvind Gupta (@buzzindelhi), a key architect of Narendra Modi’s social media campaign during the last Indian general election. Reports in The Hindu (26 Dec) and The Sunday Times (28 Dec) were never fully confirmed.

Despite this compelling evidence, the Sirisena campaign’s social media engagement did not improve in strategy or coherence. Was it a lack of vision, or capacity, or both?

For example, right up to the Election Day, the campaign did not clarify whether there was an official Twitter account for the candidate. In the absence of one, tweeps were left guessing which Twitter handle to engage (@MaithreepalaS, @MaithriNextPres or something else). On 9 January 2015, @MaithriNextPres account was changed to @SLPresMaithri, but as at this writing, remains unverified.

Not that there was much engagement by either campaign. Campaign related social media accounts were used mostly in the broadcast mode — for disseminating updates, statements and images, rather than for actually discussing any issues online. Despite persistent attempts, I failed to elicit any response from either campaign.

Volunteers and Critics

How to explain this mismatch between opportunity and deployment? My guess: the new media tools were being wielded by political party officials and/or their PR companies – all saddled with old-fashioned mindsets. In their reasoning, perhaps, citizen engagement was a luxury or nuisance…

Meanwhile, running up social media numbers – of followers or ‘friends’ – was given priority, at least by the Rajapaksa campaign. They had the incumbency advantage and an already well established brand name.

In contrast, the Sirisena ‘brand’ – as a distinctive candidate, not part of an XXL Cabinet of Ministers — had to be promoted within just a few weeks. That it happened fast and well enough to win the election was probably due to the web’s inherent bias towards the underdog.

The Sirisena campaign’s social media efforts seemed mostly voluntary. It was dominated by passionate — if not always well coordinated – individuals. This rebalanced, to some extent, the huge asymmetry of resources between the two campaigns.

Among these volunteers were cyber-savvy youth who were neither party loyalists nor ardent Sirisena fans. They were drawn to it more by the common opposition candidate’s pledges of political reform and good governance that resonated widely among this demographic. A decade of accumulated frustrations over the incumbent’s mal-governance probably enhanced that appeal.

Then there were others who – like myself — critiqued both campaigns, while advocating larger ideals than the promotion of any particular candidate. Many in this group are politically conscious and charged, but not aligned with any political party. Our political ideologies were different or incongruent. We were united by a common desire for clarity, discussion and debate. We didn’t wish to be mere recipients of large volumes of campaign-originated communications. Neither did we settle on just peddling weblinks from the mainstream media.

We asked inconvenient questions that ought to have been asked by the mainstream but were often left unasked — for example, on specific pledges in the manifestos, or on thorny issues like abuse of state media, government pressures exerted on telecom companies, and glaring self-contradictions of recent political turncoats.

When we did so on open, public platforms like Twitter, our fleeting messages became part of the common digital record. Candidates and campaign managers often chose not to respond to our pointed queries, but in many instances, their silence itself was telling.

Were we akin to annoying mosquitoes hovering around two large political animals engaged in an elaborate combat? Maybe, but again, our own role and its impact needs deeper appraisal.

Reflection Needed

Let’s not get carried away, though. There was no master plan let alone any hidden agenda a la Arab Spring. (Careless speculations on this were rampant during the campaign that I dedicated an entire weekly column in Ravaya newspaper to explain why an Arab Spring style uprising was very unlikely to happen in Sri Lanka.)

What just happened in Sri Lanka is not a revolution in its conventional sense (because, after everything was said and done, the transition was orderly). A well-oiled administrative system that has been holding elections since 1931 proved its efficacy again. And if the integrity of that system came under pressure even momentarily, the formidable Commissioner of Elections stood up for the due process. My tweet calling him ‘Man of the Match’ was among the most widely shared in recent days.

At the same time, some technology-related factors observed during #PresPollSL are indeed transformative if not revolutionary. Many of these are still nascent and will gain in maturity and momentum in the coming years. That is why we must study and understand them, so that we can exploit the inevitable march of digits – and not be intimidated or overwhelmed by it.

Sadly, Sri Lanka’s university-based media researchers have been blindsided by their own prejudices to realise and analyse what is going on in cyberspace. Market researchers are more aware, even if their focus is often determined by the specific needs of clients. Meanwhile, a vocal minority keeps implicating social media as a threat to our culture, public morals and even national security.

The net result: there is little evidence-based, dispassionate discussion on this emergent new reality. From advertisers and mainstream media to social activists and political parties, everyone seems to be guessing, hyping or panicking.

“Elections are unwieldy affairs, and we tend to forget that there are many moving parts: from the campaigning, and the publishing of ideas, to the listening, and responding,” says Angelo Fernando (@heyangelo), a technology columnist and author of Chat Republic (2013). “Politicians are very good at the first two areas, and in fact get over-confident because they have the ‘machinery’ to manage the campaigns and the publishing. Unfortunately, these change faster than the candidate can keep up with.”

Angelo — who has been following social media at work during several US elections – points out that even the social media we think we know and understand is changing rapidly. “It makes politicians complacent to think that they have a Twitter account and a Facebook page, that must make them seem in touch and accessible.”

In his view, tactics such as owning, controlling and displaying media (e.g. posters and large cutouts) that would have worked six years ago, don’t seem to work anymore.

Urgent challenges

Besides deeper reflection of digital and cyber dimensions of #PresPollSL 2015, we also face some on-going, urgent challenges.

The same social media platforms that helped promote democratic discussion and debate are being used by some as forums for spreading misleading and inaccurate interpretations of the result. This sophisticated form of hate speech illustrates the downside of digital tools and social media, which needs debunking.

Commenting on the under/over valuation of ethnic composition with respect to the result of the Presidential election, journalist Malinda Seneviratne wrote in his blog: “Not surprisingly these are exercises indulged in by those fixated by identity politics. They assume, erroneously, that people are essentially one dimensional and they make choices based solely on notions of identity, ethnic or religious.”

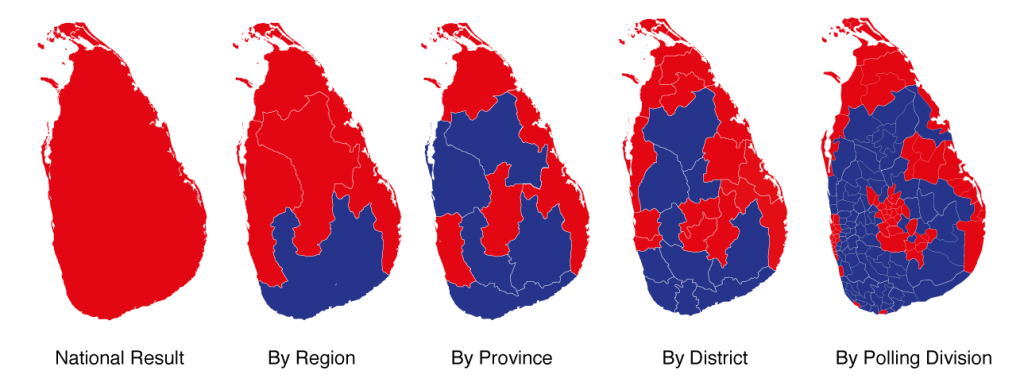

Such ethnically-charged claims are based largely on infographic maps projecting election results by electoral district or electorate. Depending on the geographical unit used, the picture on the map changes considerably. In all cases, the visual depictions are conceptually flawed.

In a timely critique, public intellectual and policy analyst Rohan Samarajiva (@samarajiva) urged: “Do not produce, publish or take seriously any infographic that shows majorities in any unit smaller than that of the entire country.

And as blogger Indi Samarajiva (@indica) shows convincingly in a blogpost, the only graph that matters is one that depicts the national result on the map of Sri Lanka. US-styled red and blue maps don’t work here because our electoral system is very different.

Suddenly, it seems we have miles to go before we can sleep.

###

Science writer Nalaka Gunawardene has been chronicling the rise of information society in Sri Lanka since the early 1990s. He is active on Twitter (@NalakaG) and blogs at http://nalakagunawardene.com.