We are discussing a photograph. It was taken by the camera of a smartphone. It has been viewed by thousands, engaged with by hundreds, and is now being exhibited at the Saskia Fernando Gallery. @colombedouin is Abdul-Halik Azeez. Colombedouin is the title of the exhibition that is ongoing at the time of conducting this interview. It is a strange place to be.

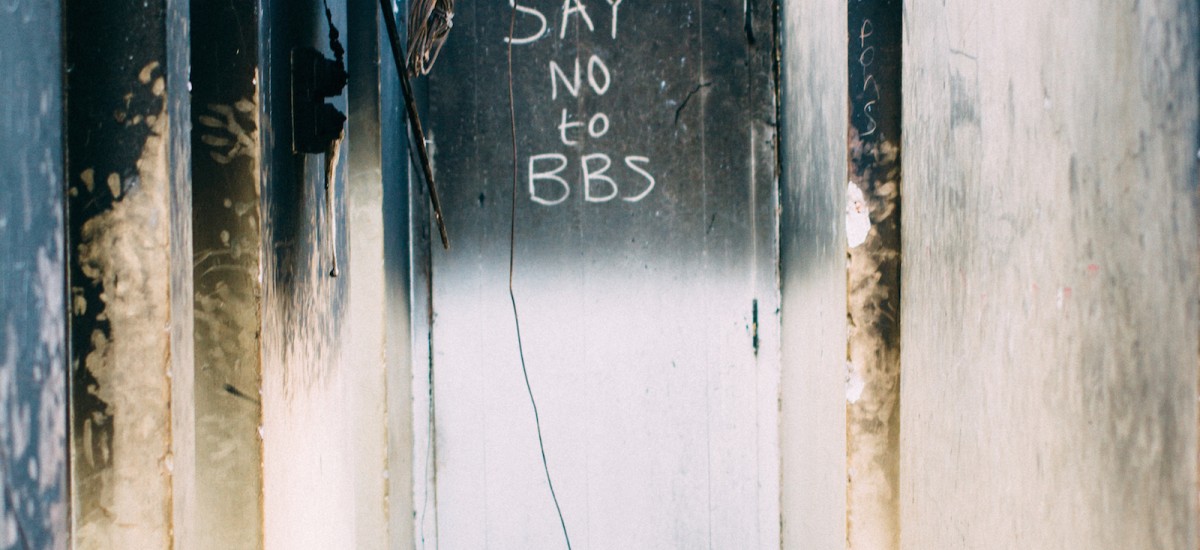

“Blowing up your Instagrams and putting them up on a wall gives you a different perspective of what was captured,” says Abdul-Halik, as I point out to him that this photograph we are discussing reads ‘BBS pons’. He had not noticed this when he snapped this photograph among the 200 or so he took when he visited Aluthgama, this year, a week after the riots.

“I couldn’t stay away from it,” Abdul-Halik explains, “My excuse was that I was going there to help in some way. Which, anyway, I was.”

The photograph that we are discussing is, in his words, “just another broken down expensive house. It was one of the most sprawling in the neighbourhood. I could tell that it belonged to one of those big, established families from the way it was annexed with rooms in unexpected places. It had grown over generations with no method to the madness.”

I ask, then, of his observations on the manner in which these attacks took place.

“Well, there was definitely a method to the madness that destroyed the houses – to know where they were located, and to have the courage and arrogance to ignore the curfew.”

Why take pictures of graffiti in a scene of destruction? Isn’t graffiti considered, by a majority mentality, to be vandalism – another form of destruction?

“I look for the intention behind graffiti. It is my representation that counts, though I try to be objective. I knew I wouldn’t be able to not document the aftermath. It was not only an attack on the Muslim community, but also, it had taken place in a country just emerging from 30 years of conflict.”

I then ask whether he practices discretion when documenting violence, to which he responds that location and context are what need to be considered.

“In Hyderabad, I witnessed a Shia Muslim tradition where the streets were full of bloody men as they flagellating themselves. When their palms struck their chest, water would mix with blood, spraying into the air like a Kill Bill movie.”

Abdul-Halik did not post any of those photographs onto Instagram. Instead, he chose to post a photograph of a child, after the event was over, bandaged, with traces of blood still on him.

“Here, I tried to practice subtlety.”

Our conversation tails back to a lecture he delivered at the American Center, where he quoted Nathan Jurgenson’s take on Instagram as Decay Porn: a fetishization of the offline, characterized by the affectations of nostalgia inducing faux-vintage filters. Abdul-Halik admits that his work does consist of this genre.

“I am fascinated by things that are old. It is part of my world view. We glorify the present and denigrate the past – which is where the present is heading. This brand new thing, today, is transient.”

In this modern age, where human movement is fluid from A to B, people do not interact with each other on the streets. They are glued to their smartphone, flicking through Instagram to consume “culture” and “reality”. I am referring to the developed world, and ask him if he feels that it is the direction in which the developing world is headed, too.

“We are boxed in by the vocabulary of progress. Have you seen rich kids on Instagram?” he asks, “A lot of Instagram is full of selfies and self-indulgence.”

According to Abdul-Halik, in order to document life and be able to observe phenomena meaningfully, you have to be ‘unplugged’.

“Such Instagrammers tend to be in a socio-economic status in which they are self-actualized. That is why we see meaning in what other people pass by,” he explains, “Instagram allows you to rebel against the status quo that Instagram both represents and is.”

This status quo, however, is coming into its own on Instagram, as Abdul-Halik observes, “When I joined, Instagram was much more fluid. You could carve out a niche and get noticed much easier. You could rebel all you wanted, but, now, that dynamism is becoming more rigid. There are archetypes like the #selfie, #foodporn and #puddlegram that are defining a way of being and a way of seeing on Instagram.”

Then, there are hashtags, which, we agree, are sometimes a sell-out thing to do.

“If you’re in it simply for the ‘likes’, you are undermining your own integrity. It’s a balance. You need an audience. You have to reach out. Hashtags are simply a very blatant way of doing so. But hashtags also serve the function of making your content searchable. I have used them in the past and continue to use them in a way I see is appropriate.”

Halik’s journey has seen him go from a few followers, starting with his friends and the old blogging community, to organizing an InstaMeet where several Instagrammers congregrate at one location and do what they do, then delivering a lecture on Instagram and the sub-culture associated with it, to being recognized by Instagram as a “featured user”, enabling him to gain over 20,000 followers, to where he is today – exhibiting his work, curated by Saskia Fernando.

“I took a step aside and did not intervene in the process of curating the exhibition,” Abdul-Halik explains, as the process of curating work is not just relevant to a gallery, but also to Instagram, as he has always consciously curated his Instagram feed.

“With low followers, you have nothing to lose. Your feed is curated by instinct. With many followers comes a satisfaction and a reluctance to post anything that might harm that.” “

This is where integrity is questioned, again.

“This runs the danger of affecting the purpose of getting onto Instagram in the first place.”

I ask him what he makes of the idea that form outlives content, and he adds that, in this case, it is the “medium” that is the content.

“The content is moving from my Instagram feed to the gallery to people’s walls in their homes. I find this journey of the content through each medium intriguing to observe”