A few weeks ago, in the town of Kilinochchi in the North of Sri Lanka, I visited a large factory. An exciting visit to Kilinochchi, because just six years ago, the likes of you and I would have felt that this town was on a different planet. It was not accessible to us, being under control of a determined rebel, who, generously endowed with brutality and stupidity in equal measures, put tens of thousands of innocent people to be massacred on the firing line between him and his equally callous foe. Today, to our delight, Kilinochchi is just one hour drive from Jaffna and six hours and ten minutes by train from Colombo.

Observe from the North: a friend from the newly established Faculty of Engineering of the University of Jaffna was able to greet me at the Kilinochchi railway station at 1:00 PM, then drive to Thirunelvely for a meeting, and be back at 5:30 PM to join me at dinner. He could do that because the highway is in good shape. His Faculty that wasn’t there last year is up and running, though in temporary buildings, with a few dozen students and about ten bright young lecturers. The potential of the place and the people I met was impressive. That there was much hard work to be done, and that there was the space to do it in, was striking.

Observe from the South: if you take a train ride to Kilinochchi, you can still see Station Masters using Victorian signalling systems, passing bronze tablets through engine drivers — a secure system ensuring only one train is on the track between any two stations. Seated on comfy seats of air-conditioned carriages, you will notice two step changes when you pass Vavuniya: (a) the journey becomes suddenly very comfortable – the railway tracks being brand new to the north of Omanthai, the train travels primarily in one direction, rather than the usual six degrees of freedom it enjoys on tracks laid during Suddha (white man) times in much of the rest of our country; and (b) density of army personnel you come across suddenly increases – stationed there due to a security necessity of avoiding our country go down the war path once again, and the social and political necessity of demonstrating who the real boss is. Real or imagined my inferences are, you judge.

At the factory in Kilinochchi, I observed two men in conversation. One was a manager of the factory. The other, to my pleasant surprise, was the Sri Lankan Tamil fellow Sivapuranam Thevaram, my drinking partner in Bridgetown pubs. They were speaking in English, despite having two other languages — Sinhala and Tamil — in common between them. That should not be surprising as command of the English language opens many doors which otherwise remain closed. Even better, English has its own beauty. For example I can’t think of another language in which you can insult someone by saying “with all due respect!”

Now Sinhala and Tamil are, according to some scholars, very different. The former is derived primarily from Sanskrit, an ancient language at the root of the Indo-European family, and has evolved substantially over several millennia. Tamil, on the other hand, is from the Dravidian family, with origins in South India, and has stayed fairly constant, over an equally large timescale. They certainly differ a lot in phonetics. For example, Sinhala diphones /ga/, /ha/, / ka/ are represented by the same character in Tamil, and though in wide use, they are absent in classic Tamil. Similarly, you won’t find the same sharp distinction between /la/, /La/ and the retroflex /zha/ in Sinhala.

What a good starting point to define the differences between us, and fight it out?

But if you go slightly deeper into the languages, as Thevaram’s good friend Brave Lion (not his real name) — an expert in the field of Computational Linguistics — had explained, the morphological and grammatical structures of Sinhala and Tamil are almost identical. Compare the way you modify words: /amma/ (mother), /ammage/ (mother’s) and /ammata/ (to mother) with similar morphological changes in Tamil /amma/, /ammavin/, and /ammavukku/. Do you see similar structures?

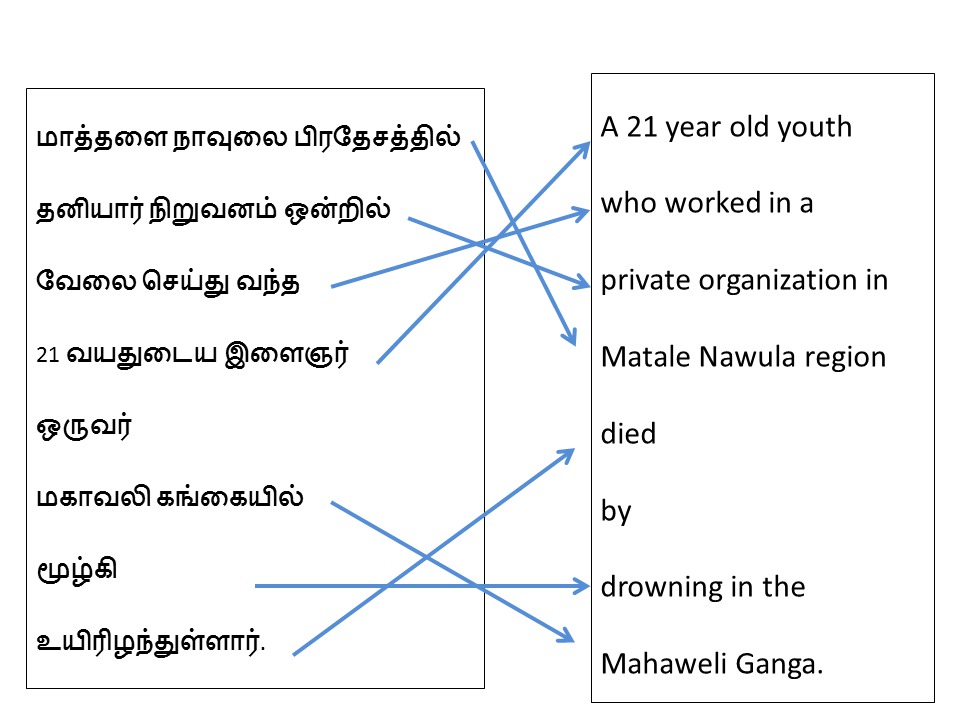

Go even deeper, and consider phrase movements shown in the figures below. Do you see the one-to-one mapping between Sinhala and Tamil, both of which differ so much from English?

Superficial differences in phonetics disappear when we dig deep down into grammatical structures, don’t they?

Is that not a good metaphor to ask the question that, if genetically similar people dress and eat slightly differently, and cling on to slightly different sets of superstitious beliefs glorified as their age old cultures, should we work towards building a political future based on their similarities, or insist on exaggerating their differences?

Let us return to the factory in Kilinochchi.

The manager was explaining the set up in the factory. They had over a thousand employees, mostly women. A clever young engineer explained how efficiency in production was optimized. She had done extensive work study calculations: how long does it take to move a small object from one place to the other, to cut the object into the right shape, to fix the pieces together, to fold it into the right shape for packing, to stich the correct label in and put the finished product into the box for export. She can then measure how efficient each worker is. There is a target to be met and there is bonus payment to be gained for doing better than the target. “Their basic salary is about Rs. 10,000 per month,” the Manager said in response to Thevaram’s query, “and I have a highly efficient and motivated workforce here,” he said with a sense of pride.

Being bombarded with terms like “efficiency,” “work study,” “productivity,” and “bonus payments,” — notions that form the foundations of capitalism – made my friend rather uncomfortable. Thevaram is from the Left of politics. Though he has never read Marx, associations on the left bank of LongRiver (not the real name of the river) at HillTop University (again, not the real name), had cultivated in him a deep sense of suspicion about capitalism.

That discomfort Thevaram felt in the factory was, however, short-lived. As he looked across the factory floor, he made eye contact with one of the young women working there. Just a moment’s glance when she took her eyes off her much practiced routine. Her beautiful eyes pierced through him and jogged his memory. They told him a story. It was the painful story Thevaram’s wife’s cousin’s cousin had told him a few months back during a visit to Bridgetown.

This wife’s cousin’s cousin is from a farming family in Strawberrykulam (name changed to protect identity), of two boys and two girls. As the war intensified, the boys, considered to be of relatively higher risk were sent abroad by selling part of the land they owned. After rather perilous journeys, one through snow covered Serbian mountains and the other through the cargo holds of a container ship, they eventually settled in England. The young girls lived with the parents.

Then there was a day in 2008, a recruiting team of the striped ones arrived to take the older girl away. One member of each family was needed for the war effort. The girl was scared, ran away and hid somewhere. They searched all over the farm and couldn’t find her. So they took the younger girl. She was kicking and screaming. The parents were begging the little girl be spared. The recruiters had come well prepared with sticks and beat the parents who stood in their way. As they dragged the girl along the gravel road, the soles of her feet split and bled, the brother — the wife’s cousin’s cousin — had reported with tears in his eyes. Hearing her sister has been caught, the older girl surrendered. That did not mean the release of the younger one – the recruiters got two for the trouble of one.

Perhaps a bonus payment was received for their efficiency, who knows? After all, the rebellion was not against capitalism, was it?

Thevaram stood in silence on the factory floor, staring into the eyes of the young worker. What was her life six years ago? Could it have been what the wife’s cousin’s cousin reported? Would she have been dragged away from home, absorbed into the fighting force and sent to the front line with explosives strapped to her belly? Would that fight and the illusion of the “promised land” have been a better choice for her than being a factory worker now, whose efficiency at work was subject to meticulous analysis for the chance of a bonus payment – the essence of capitalism Thevaram dislikes?

The moment’s silence from Thevaram brought out an amazing reaction from the manager, who said “you are right.”

How very strange?

“Right about what,” I hear you ask. After all, during the preceding moment Thevaram had not spoken anything.

“Several of the girls here were ex-combatants,” the manager said, “they were held in Boosa and places like that.”

He certainly was thinking what Thevaram was thinking. There is no need for language when your thoughts are synchronized, is there? None of the three languages they had in common between them was needed.

You might ignore this as a minor detail, but the subsequent conversation of the two men was in a mixture of Tamil and English.  On his way back, at the Kilinochchi railway station, Thevaram photographed a plant – a tiny palm with fresh green shoots. He shared it with friends as the metaphor he so desperately wanted to see in Kilinochchi, reinforcing a sense of relief in him.

On his way back, at the Kilinochchi railway station, Thevaram photographed a plant – a tiny palm with fresh green shoots. He shared it with friends as the metaphor he so desperately wanted to see in Kilinochchi, reinforcing a sense of relief in him.

Yet the measures taken by the gardener who was claiming to protect the plant seemed totally disproportionate. As you see, a razor-sharp barbed-wire fence has been erected around the plant.

The gardener appears not to have read modern history books which record that the war in our country ended more than five years ago.

Are his intentions honourable?