In the post-war phase, discourse around women and their rights remains extremely weak. As such, attention must be paid to the day-to-day increase of violence against women and girls across the country. The continuing ethnic issues and insecurity together with other socio-economic factors, including the rising cost of living, have placed a great burden upon the women in the North and East as well as women island-wide who have faced the consequences of the war. Systematic steps have been taken to dismantle democracy in Sri Lanka. The judiciary, which was once considered an independent institution that had a few women holding top positions including that of Chief Justice, has since been entirely compromised. In 2012, the impeachment of Chief Justice Shirani Bandaranayake in an unconstitutional manner provided us further insight in to what has become a increasingly totalitarian State.

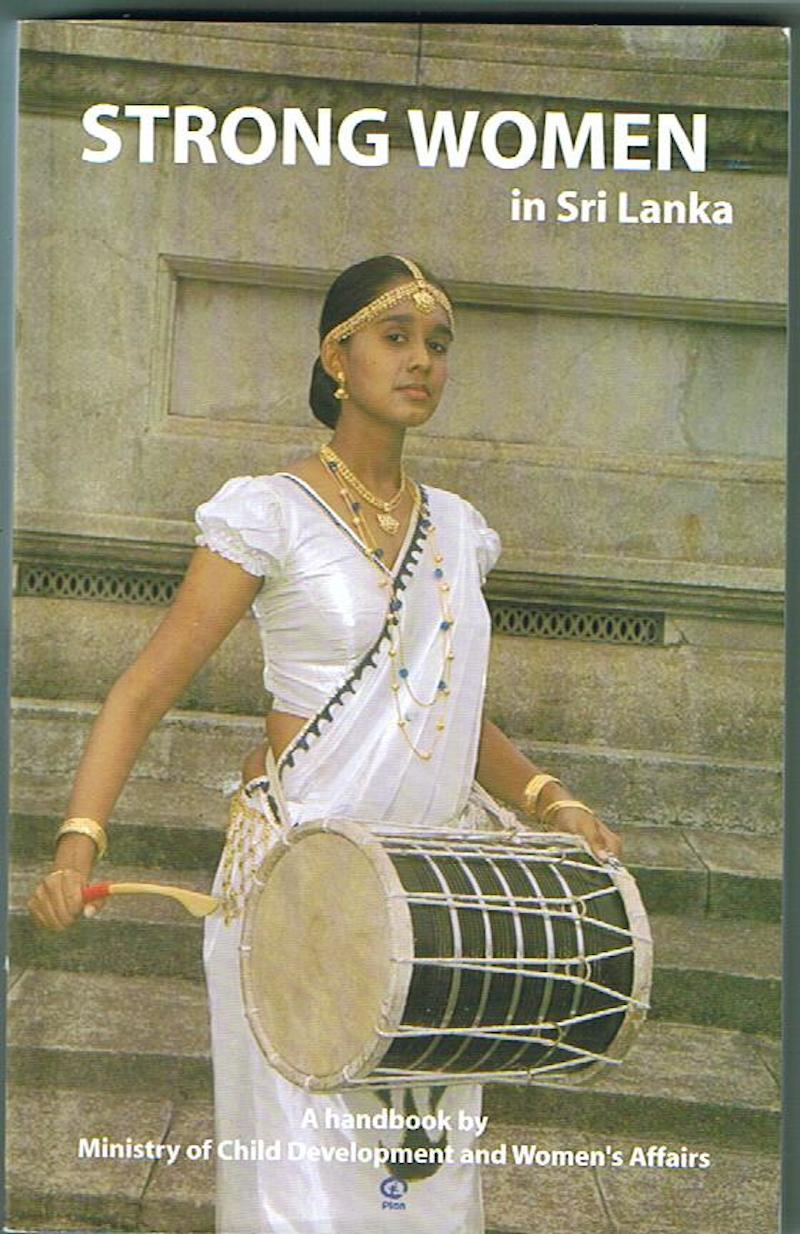

Recently at the “Deyata Kirula” event that was held in Kurunagala, the Minister for Women and Children’s Affairs presented a book titled “Strong Women in Sri Lanka” to the public. This English language book listed 47 women in various fields in 2012 as “strong women”.

The term strong women connotes women who have posed a challenge to patriarchal norms and have been able to rise above the various strictures placed on them by society and family. While the women in these books are indeed women who have made some impact in politics, education, the public sector and culture, many of them are women from the ruling party and women holding strong political positions within the party. It is therefore important to question this and force a look at the real women leaders in society. Furthermore, it must be noted that this publication focuses on women primarily from a singular ethnic, class, language and political background. Thus, for a book titled “Strong Women in Sri Lanka” it appears that little attention has in fact be paid to the word ‘strong’.

In this day and age women play an important role and are leaders in numerous and varied fields. The exclusion of women from the North and the East and other grassroots women therefore reflect the level of discrimination women face as a direct result of their gender, ethnicity, class, caste and religion. This book further reflects the limited knowledge and understanding that the Ministry of Women and Children’s Affairs has on rural women their achievements and their contributions towards Sri Lankan society.

If we look at the political arena in our country, the women in politics have typically been women who have filled gaps left by male family members or women who have achieved success and popularity in other fields. Ideally women who enter the field of politics should be those who challenge the male dominated space and fulfill their duties as representatives of their constituencies. In this regard, we also note that UNP Member of Parliament Rosy Senanayake, who has raised several women’s issues has not been included in this book.

Thangesvari Kathirgamam who was elected following the Parliamentarian Elections in 2004 and who is from Kannankuda in Batticaloa; Saraswathi Thevanthirum who won elections held in 2011 in Mullaiteevu after three decades; Jensila Majeed, who was evicted from the North by the LTTE and has challenged social and cultural norms through her work on women rights and equality for 22 years and was awarded the US State Department’s International Women of Courage Award in 2010 and Shila Irudayaraj from Jaffna, who was nominated in 2005 for a Nobel prize with 1000 other women from 150 countries for her work on women who have lost their husbands; all these women find no mention in this book.

The Ministry of Women and Children’s Affairs also does not consider Chandiraka Kumaratunga who was the 5thPresident of Sri Lanka for two consecutive terms and was also the 1st woman President of Sri Lanka as a strong woman. Furthermore, women such as the former Chief Justice of Sri Lanka, Shirani Bandaranayake or internationally acclaimed human rights and women’s rights activist Sunila Abeyasekera who established several organisations for human rights and for women’s rights, Radhika Coomaraswamy who was the Under Secretary General of the United Nations; scholar and academic Kumari Jayawardena, who’s contribution to political science and women’s histories, have all excluded in this book. Women who have earned space and acclaim in fields that historically excluded women, women writers, artists, dramatists and journalists who have courageously written and expressed dissenting views and raised important issues, all find no mention. It is clear therefore, that human rights and women’s rights activists, women from other political parties, critics of the current repressive government have been consciously excluded.

Thus, it appears that pleasing the political party in power and maintaining the status quo has been the sole aim of the publishers of this book.

The Ministry of Women’s and Children’s affairs is mandated to work towards women’s empowerment and equality. However once again it has failed to do so, instead exposing its ethnic, religious and class bias. The Ministry’s opinion that only women working in the field of politics and that too mostly in the ruling party, and government sector are to be considered ‘strong women’ is in line with the overall regressive attitude of the Sri Lankan government towards women and women’s rights.

Women’s Action Network is a collective of eleven women’s group from the North and the East.