“I do not say you can attain purity by views, traditions, morality or conventions, nor will you gain purity without these. But by using them for abandonment rather than as positions to hold on to, you will come to be at peace without the need to be anything.” – Buddha

A way of non – judging

Since the Buddha taught a doctrine of non-self it would not be too difficult to reject the rigid Sinhala Buddhist viewpoint of race and religion as self as a perversion of the true dharma. However setting up such a clash between the ideal and actual does not help; something the western oriented proponents of human rights have yet to learn. To say ‘I am right and you are wrong’ is not effective communication.

There is NO ideal in this world where we are all fallible human beings. We must relate with actuality, keep our minds open and trust in the winds of change or impermanence. The middle way calls for principled engagement without judging – a point of tremendous importance. This is the spirit of this essay.

The Sasana in Lanka was preserved by holding on

Buddhism in Sri Lanka has become – in the eyes of many – a name without a corresponding reality. In popular imagination the sasana is largely associated with symbolic places, acts and rituals and their maintenance has been the maintenance of the sasana. The sasana here is not the creation of meditators on the esoteric fringe. It is a more participatory and collective exercise; and act of faith tied up with an ancient identity and sense of belonging. It has more to do with the form of Buddhism rather than its elusive substance. It is quintessentially an act of holding on; not an act of freedom and letting go. The Sinhala Buddhist knows one important truth. This sasana was not preserved by letting go but by tenaciously holding on.

This is the reality of Sinhala Buddhism and it is a reality that we must come to terms with as one that sits harmoniously with the temperament of compromise, moderation and complacency of the exemplary Sinhala Buddhist. At the same time this complacency can descend from a mere winking at lapses from the five precepts to active encouragement of their violation – especially in times of conflict and where the recipients of violations are ‘enemies.’ Right now we are facing such an extreme scenario. However dealing with mere manifestations is not the Buddhist way. We need to understand the causes, the historical roots.

Historic choices of a conservative Sangha

How was it possible to turn the Buddha’s doctrine on its head in this manner and use it for the purpose of worldly objectives, including exploitation? The old Brahmin – Kshatriya inter-dependence was replicated before and after the mahindagamanaya (the arrival of Arahat Mahinda with the formal Buddhist teaching to the island) and Buddhism pressed into service for strengthening the new political order. This perhaps was a natural development within a small island that sought to achieve an independent political existence within the South Asian world.

The period of 161 years from the enthronement of Devanampiyatissa (250 BC) to the restoration of Valagamba (89 BC) was a baptism of fire for the young island nation as it fought and struggled to stand on its own feet in the face of three foreign conquests by South Indian adventurers. From the horse traders Sena and Guttika through Elara to Pas Dravida the total period of alien rule amounted to 80 years within that period of 161 years. And while the war of liberation by Dutugemunu was a celebrated people’s war – backed totally by the monks of Mahavihara, Valagamba did not enjoy such unqualified backing – a circumstance that led to the emergence of Abhayagiriya as a rival monastic centre after the re-conquest.

Faced with a hostile and victorious monarch the Mahavihara monks adopted radical counter-measures codifying the Buddhist canon and establishing a hierarchy within the Sangha that favoured the Dhammakathika’s or preachers over the Pamsukulikas – the rag robe wearers and meditators. This division within the Sangha very early in the life of the Sasana in Lanka probably reflected a deep difference of opinion between monks who aligned themselves closely with society (Dhammakathikas) and those who sought a radically independent way of life following the tradition of renunciation in India (Pamsukulikas). The resolution of this power struggle by upholding the primacy of learning over practice led to a worldly Sasana – but one that endured over time with its fortunes linked directly with the monarchy and the people.

While the meditating forest monk who strives for enlightenment following the path of practice was venerated then and now the post Valagamba Sangha ensured that the spiritual leaders of society would always be those monks within the ‘establishment’ who fostered and maintained the interests of Buddhism as state religion. It would also be the same ‘establishment monks’ who would maintain and protect the authentic externals of the sasana, the relics, texts and ancient monuments (including the Atamasthana) that would be resorted to by the people for popular worship and pilgrimage. Once the needs of both state and society were ensured in this manner, mind cultivation or bhavana – as a spiritual technology of wandering mendicant monks was marginalized as an optional activity.

This ‘pragmatic’ formula worked to maintain the balance of power and 518 years of peace ensued before the next foreign invasion of Buddhist Khalabras in 429 AD. The hela text was converted to Pali by the Indian Monk Buddhagosha before the Kahalabra occupation and the hela original was destroyed. This moved the written teachings away from the ordinary Sinhalese further consolidating the position of monks as interpreters of the Buddha dhamma.

When the liberator Dhatusena (455-473 AD) commissioned his uncle the monk Mahanama to compose a politico-religious history of the island a clear need was perceived to develop a unique identity that went beyond a shared Buddhist identity with mainland India. This was a creative and empowering act for a people who originally united around the sasana but then came to develop a distinct linguistic and cultural identity.

The Mahavamsa was a historical first in the pan Indian cultural area as it was the first time a history was constructed from external events. The great Indian epics like Mahabharatha and Ramayana spoke of an inner world, what Kathleen Raine called ‘soul’s country.’ With the earlier demotion of forest monks within the ecclesiastical hierarchy in the first century BC followed by a western style history in the 5th century AD the Sinhalese were fashioning their own unique philosophy of life under Lankan skies. These were unmistakable signs of an early western orientation.

Disappearance of self within the collective

These were historic choices that sought to ‘hold on’ and strengthen a vulnerable polity on the edge of a massive sub-continent. The Buddha, the dharma and the Sangha were all appropriated quite decisively by orthodoxy and the establishment in this country. On the other hand Buddhist thought and action in India has always been independent of conventional society as its most powerful critique. This is how the Dalits or untouchables flocked to its standard under Ambedkar during the Indian Freedom Movement.

Dhatusena was a monk who disrobed to liberate the country. The Buddha as we know renounced kingship to liberate himself. It is well known that Buddha’s own clan was annihilated by a neighbouring kingdom during His lifetime.

However such Himalayan heights of detachment find no place within this island where the Sinhala Buddhist must fight to ensure that this piece of real estate remains the property of the Sasana for its prophesied period of 5000 years. It is the same logic that was used effectively by the Dhammakathikas after the restoration of Valagamba. ‘if the teachings themselves vanish, what will we practice?’ Likewise the argument goes that without the land the Sasana will disappear.

Of course from a classical Buddhist perspective the end does not justify the means. In any discussion of means and ends comes the most critical third factor – the individual human being who makes the choice and his or her spiritual development. When this is sacrificed for a concept like the ‘security of the state’ or ‘maintenance of the sasana’ we must ask the questions for whom is the state being secured and for whom is the sasana being maintained? Any Buddhist society must guarantee this freedom for the individual to think and decide without imposing a collective choice. Ultimately for the Sinhala Buddhist the sole refuge is practice and everything else (helping others, society and country) must be an extension of that practice. To forsake the practice for worldly goals is an act of a worldling or puthujjana and such persons cannot advance either themselves or others.

What is the purpose of building a Buddhist house if we are not going to live in it? Why develop Buddhist symbols and spaces unless we are going to put the teachings into practice? As Shantideva once asked ‘will the sick become well merely by reading the medical texts?’ These are the questions that come to mind when we look at successive efforts of the Sinhala Buddhists to revive the Sasana after British colonization in 1815. The answer probably lies in the use of Buddhism to strengthen a collective identity and strengthen the establishment without using it in the manner intended by the Thathagatha – to strengthen and enlighten the individual.

Maintenance of elitism

The hierarchical position of monks within the sasana and their hallowed role as ‘guardians of the doctrine’ have made them authorities as to what the doctrine states and means in popular understanding. The Buddhist layman today is probably better read and better informed about the dharma and its practice today than at any other time in the history of this country. However the weight of history remains heavy on society.

As Prof. Senaka Banadaranayake pointed out in his recent book Continuities and Transformations: Studies in Sri Lankan Archaeology and History:

The Sangha’s ideological position gave them considerable political and social influence, and they enjoyed in certain periods, varying degrees of immunity from the fiscal and judicial authority of the royal officials. Economically, as great land owning institutions, embodying a form of ‘private’ (i.e. corporate, non-state) ownership of land, they were directly involved in the generation and acquisition of surplus, and had therefore an independent economic existence. As for their connections with the secular elite, evidence from EHP-1 the MHP and LHP and other parallel situations elsewhere in Asia, indicates a close relationship between monastic order – especially its higher ranks – and the secular landowning nobility and gentry. It was exclusively from these latter social groups that the royal officials were drawn, and also at least a substantial section of the Sangha itself.

[EHP – Early Historical Period from 3rd Century BC to 6th Century AD

MHP – Middle Historical Period from 6th Century AD to 13th Century AD

LHP – Late Historical Period from 13th to the 19th Century AD]

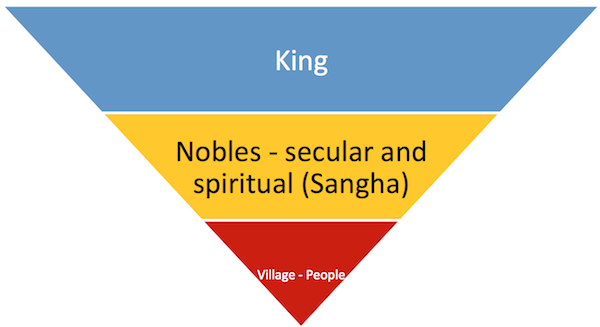

The following inverted pyramid showing the hierarchical power relations in Sinhala Buddhist society illustrates the strength of this top down cultural ideology – an ancient symbolism that continues to sway the masses in this land. It is a power that is overwhelming in terms of the strength of the ideas, concepts and myths which have been appropriated by those in power in Sinhala Buddhist society.

[Keerthi Sri Rajasinghe’s image is positioned close to the Buddha at the Dambulla Cave Temple. The message is crystal clear. The King as protector of the Sasana stands close to the Buddha within the spiritual hierarchy. Those who worship the Buddha do in fact worship the king by implication. This is secular colonization of the image of Buddha.]

Loss of culture, civilization and morality

Maintaining inequalities became more and more important to the Sinhalese elite as our society stumbled from crisis to crisis with the displacement from a strong irrigation culture that held the people together for one and a half millennia. Thus the ‘collective good’ became increasingly identified with what was good for the elite.

Displacement from Rajarata with the invasion of Kalinga Magha in 1215 was the loss of the heart and soul of Sinhalese culture. The forced drift to the south west entailed multiple losses – to spirituality, autonomy, social cohesion and national unity. These losses were never confronted with honesty and resolved. Instead the Sinhalese retreated into an ethnic and caste consciousness that simply blamed ‘others’ for all ills. We got stuck in the denial mode and held on to the myth of continuity.

The period that began with the Dambadeniya Kings can properly be termed a ‘civilization’ that succeeds a culture that has died. (This is an application of Oswald Spengler’s distinction between culture and civilization in his famous work Decline of the West.) Once the period of internal, spiritual and creative growth has ended the civilized man lives externally by imitating the old cultural symbols. Of course this period had its share of good kings, scholars, artisans and craftsmen – some of whom continued to develop the earlier art forms. But these individuals could not define their era in the way those who live within a living culture do. The fundamental character of society from Dambadeniya to Kandy was stagnation. Spiritually, the self reliant Sinhalese regressed to place their faith in protector Gods while maintaining a formal adherence to Buddha dharma.

Even this period of external preservation ended with the Colebrooke-Cameron Reforms of 1833 which dismantled the political and socio-economic forms of the Sinhalese to replace them with western forms. As Prof. Banadaranayake observes we thus became the only Asian country (with the exception of Philippines) to be most heavily impacted by European colonial penetration.

Early British policies included the brutal suppression of the 1818 rebellion and the killing or deportation of all anti – British Kandyan leaders. This left the society orphaned and at the mercy of a clique of local collaborators – the Mudaliyar class. The new political, administrative and legal forms and the new economy introduced after 1833 had no visible relation to what the Sinhalese were familiar with for 2000 years. Local society and culture simply followed suit aping a dominant English language and western culture. Although the Anuradhapura man was creative and eclectic to go beyond Indian cultural forms when the occasion demanded the colonized natives were not free to look beyond slavish imitation of the powerful white man and the self interest that lay in servility and conformity.

Together the Kalinga Magha invasion and Colebrooke Cameron Reforms were responsible for the eradication of local culture and civilization respectively. They were both acts of violence that deprived the people of this country of their identity and autonomy. Of course there is a very important local share of responsibility for the subsequent failure to re-establish democratic governance on a foundation of true consent and non-violence.

There was a local failure to face facts – learn from past mistakes and move on. There were no spiritual leaders to guide the people out of darkness after both debacles. When education itself was taken over by the British Colonial Government and precedence given to Christian Missionary education the seeds of future conflict and violence were sown. The Buddhists, Hindus and Muslims formed their own denominational schools in an act of opposition to safeguard their own threatened identities. My suggestion is that a civilization ends when cultural symbols cease to be used for rightful purposes but are actively abused for egoistic, sectarian or private ends. Unlike in India there were no enlightened leaders who could develop a common and shared spirituality that would transcend the divisions of class, caste, race and narrow religion that the people were being boxed into within a colonial culture.

The religious leaders held on to old forms but were unable to draw the links between the timeless universal values that bound the people together in their day to day lives. They were also unable to draw the links between the values inherent in western norms like equality, rule of law, human rights and democracy and the indigenous norms of a culture and civilization that had endured for two millennia. The religious revivals of the British period became a victory for communal identities without laying the foundation for nation building. We turn specifically to the Buddhist revival of the late 19th century.

Three giants who met and parted

The three main aspects of Buddhism in Sri Lanka can be set out as follows:

- Buddhism as state religion;

- Buddhism as communal religion; and

- Buddhism as spiritual technology

Each one of these three aspects became the primary focus of each one of the three giants of the Buddhist revival of the late nineteenth century – Ven. Hikkaduwe Sumangala, Anagarika Dharmapala and Col. Olcott. Ven. Sumangala was concerned about the well being of Buddhism as a state religion. As an instinctive royalist he even sought to link the local sasana to a pan Asian sasana that would be presided over by the Thai royalty. This failed but the quest for preferential state patronage continued to find expression in Article 6 of the 1972 Constitution.

Anagarika Dharmapala became a pioneering lay activist in a field dominated by monks but most of his energies were expended in securing ancient sites in Lanka and abroad (notably Buddhagaya) for communal worship.

Col. Olcott combined with Dharmapala to build a system of Buddhist education and the local Theosophical Society did not venture much into the spiritual side the way the Indian Society did. Olcott’s eclecticism in spiritual technology remained in abeyance here and his outspoken views on the worship of the tooth relic led to a serious fall out between the three collaborators.

Their ultimate falling apart represented an inability to integrate these broad strands as a harmonious whole. Both then and now the third tip of this triangle (Buddhism as spiritual technology) remains largely invisible – following its own rhythm and harmony without running with the crowd as its more visible and ostentatious partners are wont to do. Both then and now spirituality remains weak and true to itself biding its time until it is strong enough to challenge the first two. Sinhala Buddhism has generally held up the unique political and social context of Sri Lanka to resist a full application of the Buddha Dharma branding the eclectic and experiential versions of Buddhist practice as ‘Olcott Buddhism.’ While Buddhism in Sri Lanka has amassed a host of authentic externals (including the tooth relic) that are visited by the devout from within and without the island we cannot postpone the urgent need to realize the dharma as an authentic internal experience. Clashes relating to external physical sites will be inevitable so long as our sole focus remains on transient matter – however hallowed in popular imagination.

The crisis of the British period had clear spiritual implications – especially when the old social and economic structures were dismantled after 1833. But this spiritual crisis – the battle within, became secondary to external battles that had to be fought.

No refuge but practice

As we held on to old forms we ignored the cardinal point that knowledge of methodologies to control consciousness must be practiced and reformulated when the cultural context changes. This is what did not happen after 1215 and after 1833. It is widely accepted that Sri Lanka does not have an unbroken tradition of meditation practice unlike younger Buddhist countries like Japan, Thailand, Burma and Tibet. We may have everything in writing but we have to return to our practice to regain our place within the Buddhist world. The following Zen proverb distils and summarizes everything I have struggled to express here:

“If you have no feelings about worldly things, they are all Buddhism; if you have feelings about Buddhism, it is a worldly thing.”

The challenge of the present

There is no merit in living in a dead past; and no virtue in the unnecessary suffering created by this stubborn act of ‘holding on’ to narrow identities of class, caste, party, family, race and religion. Under the cover of these convenient umbrellas we are seeing the final devastation of the free and sovereign individual self and witnessing the emergence of a stupid, shameless arrogant ego. This is the same for all communities and all religions and right now both Buddhists and Muslims must take heed that the fundamental issue is much larger than their narrow adversarial concerns. The war was the result of an empty, heartless self. Post war reconstruction is the spiritual reconstruction of this same self – a transformation of our collective shadow into a shining spirit.