Download the report in full here, or view in inline here.

###

Introduction

Nearly four years since the end of the country’s civil war, Sri Lanka remains a divided, post-war society, as the ethnic conflict burns on. It has been fifteen months since the Final Report of the Lessons Learnt and Reconciliation Commission (LLRC) was made public. In July 2012, the GoSL released an Action Plan to implement the LLRC recommendations, yet little progress has been made on this front. Instead, a host of problems related to the judiciary, governance and militarization, among other issues continue to plague the island nation.

TSA’s third report, The Numbers Never Lie: A Comprehensive Assessment of Sri Lanka’s LLRC Progress, provides a detailed look at the Government of Sri Lanka’s LLRC progress that includes both quantitative and qualitative analysis. TSA surveyed 1,786 households across 208 GN divisions in nine districts throughout the North, East and Hill Country. In virtually all crucial areas, the GoSL has failed to implement the recommendations outlined in its own presidentially appointed commission. From questions related to disappearance, arbitrary detention and the rule of law to political rights, language policy, land, compensation and militarization, the GoSL continues to fall short of expectations. And, disappointingly, a proper recounting of the war’s final phases – a sine qua non of reconciliation – has not taken place. Sri Lanka’s grip on reconciliation is more tenuous than ever and significant changes are urgently needed in order to ensure that the island does not fall into a more pronounced period of ethnic strife. This article is intended to provide readers with a brief glimpse of TSA’s findings, the contents of the report and the urgent need for more resolute action at the HRC in Geneva.

Key Findings

TSA’s survey findings provide clear and convincing evidence that GoSL is not really implementing the LLRC recommendations. Some key survey findings:

Surrendees and Arrests

- 4% of survey respondents noted that they have surrendees in their family. Out of those, 86% of surrendees were apprehended from September 2008 to May 2009. Nearly all people surrendered to state security personnel.

- In addition 64% of surrendees were subsequently detained.

- Of those who were detained, 84.4% were sent to Protective Accommodation and Rehabilitation Centres (PARCs) and 15.6% were sent to detention facilities (both authorized and unauthorized).

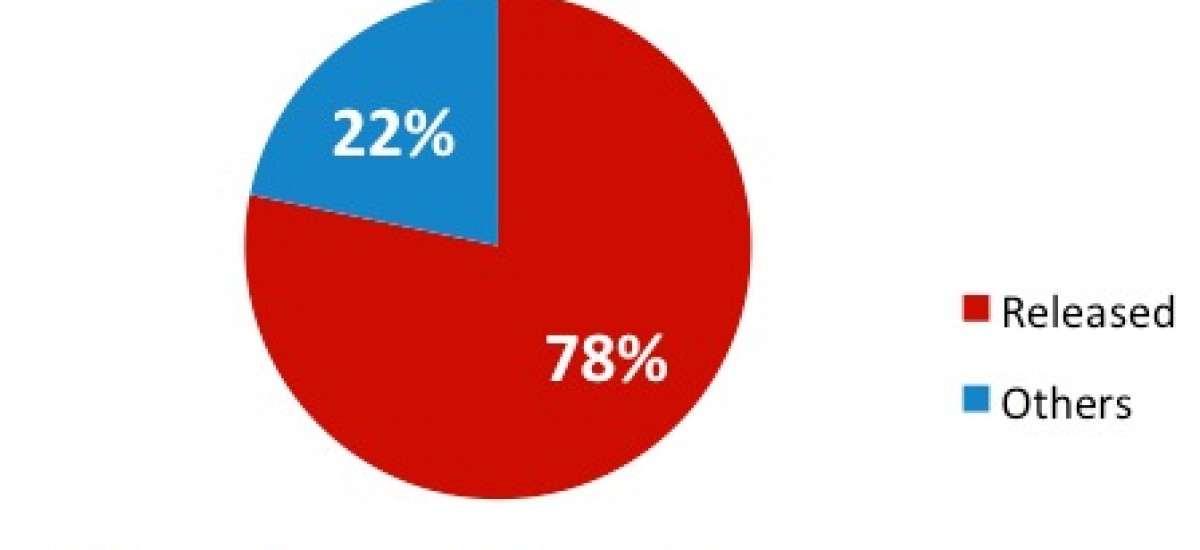

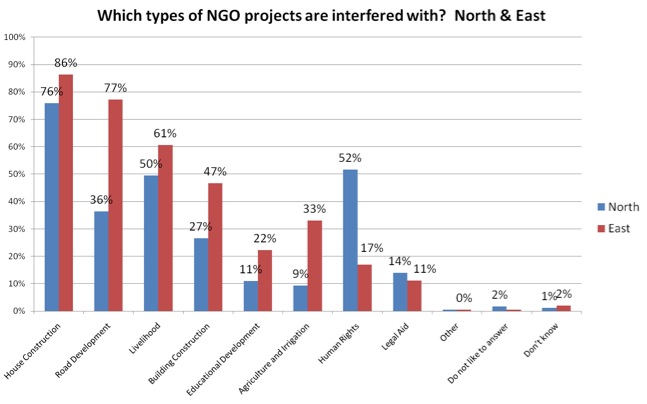

- According to TSA’s survey, more than 22% of surrendees have not been released are missing or disappeared.

Arrest and Detention

- According to TSA’s findings, 385 respondents have had a member of their family arrested. Perhaps more revealingly, an official arrest receipt – the vast majority of which (71%) were written in Sinhala – was given just over 9% of the time.

- Of those respondents who had family members who were arrested, 65% of arrestees had been the principal income earners of their respective families – which would have placed tremendous strains on an already (socially and economically) marginalized population. Regarding compensation for that arrest, only 5% of arrestees were compensated. Amongst the families of the arrestees, 3.5% received livelihood assistance.

- 43.5% of people who were arrested were forced to give confessions under duress. 53.5% people did not get legal assistance.

Detention

- 84% of survey respondents have a family member who was detained after having been arrested. Yet, out of those cases, 7% of respondents still have not been informed as to the place that their family member was detained family member – implying that these individuals have either disappeared or are currently being detained in unauthorized detention centers.

- Of those individuals being held under the Prevention of Terrorism Act (PTA) or the Emergency Regulations (ER) – 26% were detained by the state for more than 21 months.

Missing and Disappearances

- A shocking 23% of survey respondents have had a member of their immediate family disappear. The district of Ampara had the highest number of disappearances – the peak period occurred from 1987-1995.

- Out of those respondents who have had a family member disappear, an incredible 45.5% of respondents had a relative disappear between September 2008 and May 2009, during the war’s final phases.

- State security personnel are perceived to be responsible for 77% of disappearances, but the accused were investigated a mere 2% of the time.

Compensation for Disappearances

- Amongst the relevant survey respondents, 13% said that they had received financial compensation for their disappeared family member.

- Of survey respondents who are still missing loved ones, 80% have not applied for death certificates.

Political Rights

- 64% of respondents revealed that they are unable to conduct political meetings where they live.

- 87% of those surveyed thought that member of the United People’s Freedom Alliance (the Sri Lanka Freedom Party – SLFP and its allies) were able to conduct political meetings freely, whereas a mere 10% of opposition parties were able to do so.

- When asked whether Tamil representatives not aligned with the UPFA were discriminated against by the security forces, 41% said that they were.

Language Rights

- When asked whether they were able to receive services in Tamil, 30% of survey respondents said that they were not. When asked whether circulars and other notifications were sent in Tamil, 33% of respondents answered that they were not.

- Overall trends regarding language policy are very negative, but 47% of respondents revealed that they are able to sing the national anthem in Tamil. Not surprisingly, this has become much more common since the war ended.

Other Key Findings

- TSA’s findings clearly show that community participation in decision-making processes on development is far from ordinary, with 38% of respondents not consulted on planned projects.

- In addition, development projects appear to be predominantly contracted out to Sinhalese companies based elsewhere in Sri Lanka (47%) and the military (12%), as opposed to 30% for Tamils and 11% for Muslims. This includes the issuance of permits.

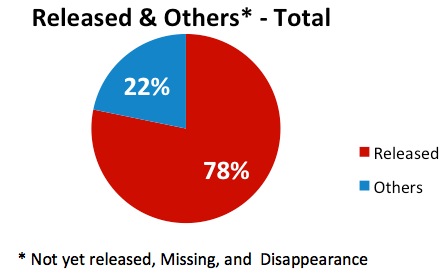

- Out of the respondents having answered that new places of worship had been constructed in their home areas, 67% indicated the new sites were perceived to be Buddhist temples, while only 20% declared new Hindu temples were perceived to have been built.

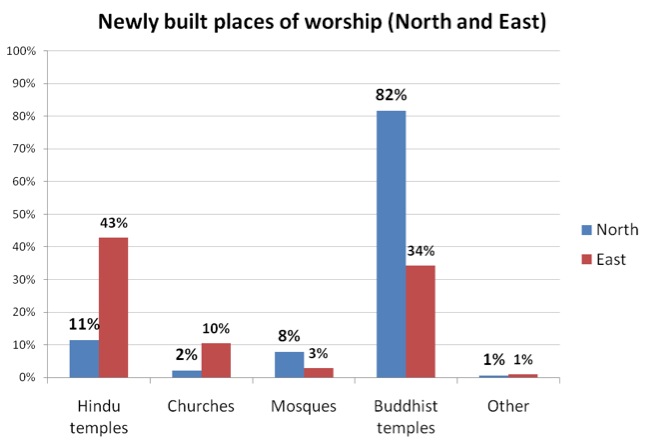

- Nearly half (43.5%) of respondents indicated that NGO projects had been interfered with. The main interfering actor was, again, the military according to 48% of respondents.

- A further 47% responded legal aid and human rights programming was being obstructed (34% for human rights work and 12.5% for legal aid).

Restrictions on Fundamental Freedoms

- 29% of respondents stated they could not meet freely in public spaces. Threats from the military were indicated as the major reason for being unable to meet for 90% of respondents.

- 21% of respondents also indicated not being able to practice their religious traditions freely. Out of these, 74% indicated special remembrance days are the most restricted events.

- According to 79% of respondents, the military is engaged in civilian socio-cultural events. Out of these, 76% mentioned their participation in temple festivals, 85% in school sports events, and 2.3% in private events such as birthday and wedding parties.

Military Occupation of Public Spaces and Private Lands

- Besides involvement in civilian activities, the survey clearly confirms the military’s consistent use of community resources, as stated by 29% of respondents. Out of these respondents, 27% indicated hospitals were being occupied by military personnel.

- Educational facilities are also being occupied, including playgrounds and schools, as indicated by 42% and 23% of those who answered.

- 10% indicated religious sites were being occupied by military personnel.

- 76% of respondents in the North and 62% in the East stated having military personnel residing close to their residential areas. Out of these respondents, 75% indicated they are situated within 5 km of their home in the North, as opposed to 55% in the East.

- 59% of respondents mentioned that security forces had patrolled their area between March and December 2012.

- On a more positive note, however, the majority of High Security Zones (HSZs) in Jaffna have been released. As of the writing of this report, 52/69 HSZs had been released.

Land Rights and Expropriation

- A significant number of families were unable to return home after displacement, as stated by 8% of respondents. Among these, 74% could not return due to a lack of basic facilities, 32% because of insecurity, 34% because of unemployment and 19% due to their lands not yet being released for return.

- 13% of respondents indicated that people of other ethnic/religious groups had recently settled in their area. Out of these, in the North, 54% of respondents indicated that new settlers were Muslim, while 28% mentioned the arrival of settlers of Sinhalese origin. 31% stated new settlers arrived between June 2009 and June 2012, and 41% mentioned they came after July 2012.

- 33% of those who stated new groups had arrived indicated these were Sinhalese, while 28% specified Muslim settlers had come or returned to claim their land, mostly between September 2008 and April 2009.

- 4% of respondents reported their private land was expropriated, 72% of whom indicated the military as the expropriating actor.

Challenges Faced by Female-Headed Households

- only 1.5% of female-headed households having had their land expropriated received alternate land (as opposed to 9% for households headed by a male). No female-headed households had received compensation.

- Only 18% of female-headed households said they will accept compensation if they receive it, suggesting that the majority still hope for their land to be returned to them.

Deaths Due to War

- 9.37a – “The Commission therefore recommends that action be taken to; a. Investigate the specific instances referred to in observation 4.359 vi. (a) and (b) and any reported cases of deliberate attacks on civilians. If investigations disclose the commission of any offenses, appropriate legal action should be taken to prosecute/punish the offenders.”

- 9.52 – “Issue death certificates and monetary compensation where appropriate.”

A proper examination of what transpired during the war’s final phases has not happened. However, there’s no question that tens of thousands of civilians perished during that time. A thorough accounting of the past is a sine qua non of reconciliation. The UN Panel of Experts report indicated that approximately 40,000 were killed during the final stages of the conflict. However, others have voiced suspicions that the figure is much higher than that – perhaps as high as 146,679 casualties.[1] Since May 2009, an enormous amount of information – ranging from documentaries to articles to books and reports – has been released which suggests that civilians were deliberately targeted during the end of the war.

End of War

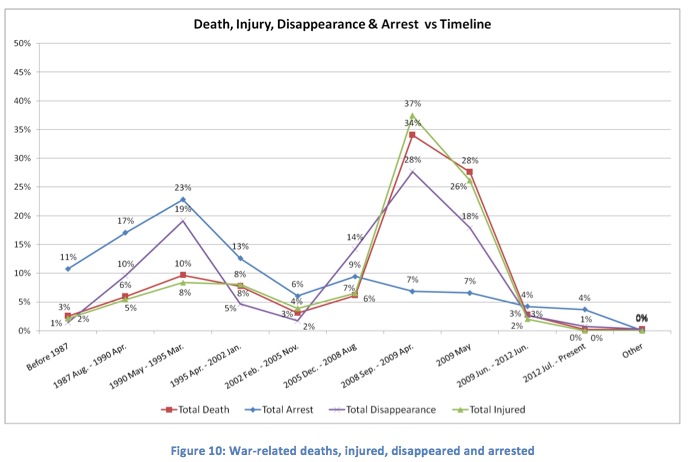

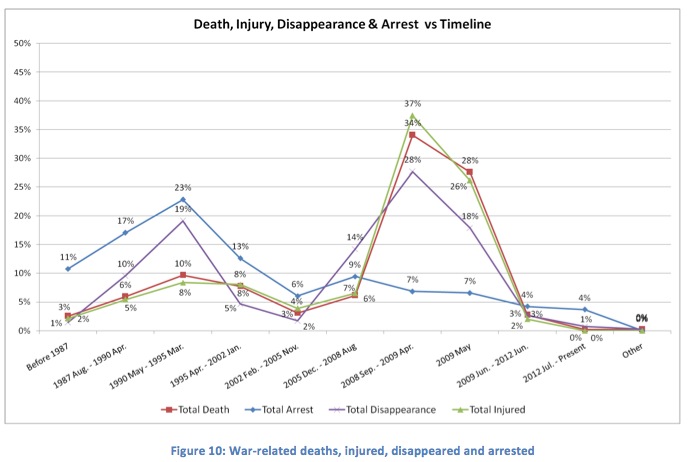

TSA findings about deaths between September 2008 and May 2009 are revealing and disconcerting.

To be clear, TSA’s death toll of 118,036 people for the final phase[2] of fighting probably underestimates the actual casualty figure because TSA has aggregated deaths from all eight districts in the North and East during that time. (This figure could also include LTTE cadres killed in battle).

For 75% of deaths, state security personnel are perceived to be responsible for the death. According to TSA’s survey, the LTTE is perceived to be responsible for 22.5% of deaths. The Indian Peace Keeping Force is perceived to be responsible for .4% of deaths. And the Karuna Group is perceived to be responsible for .2% of deaths.

Of the survey respondents who engaged with the survey question on complaining about the death(s) of a family member, 28.5% of respondents complained to the police. Out of those people, 28% had their complaint acknowledged by the police. Also, 2% of respondents complained to the Grama Sevaka. And 13.5% complained to state security forces (other than the police). Only 2% of respondents said that police initiated an inquiry into the deaths which they had complained about.

Here, the same amount of people had received acknowledgment for their complaint from the police. The police were responsive on death certificates; this is a positive thing But why would police be giving quick responses for death and not for other matters? Once someone is issued a death certificate, they are no longer able to make inquiries into the matter. This could explain why government officials are more amenable to requests for a death certificates compared to other requests. In addition, during TSA’s focus group discussions, many community members that they were encouraged to give a different (inaccurate) date on which their loved one died.

When survey respondents were asked whether they had approached any state institutions for judicial remedy, only 8.5% of respondents said that approach such institutions – in spite of the fact that the majority knew who the perpetrators were. Out of the respondents who did approach state institutions seeking judicial remedy, 1% of people had their cases filed. The country’s domestic complaint mechanism is inadequate. Sri Lanka’s institutions, its “homegrown” solutions are failing. These statistics are another sign that a Commission of Inquiry (CoI) – one that is impartial and independent from the executive – is needed.

Moreover, the lack of legal aid is again an issue, as only 3% of those people were could have received legal aid (for the death of a family member) actually got it.

And, in only 2% of cases was respondents’ evidence used in the investigation of the accused. In other areas, GoSL behavior during the end of the war was – to say the least – highly questionable. According to the MoD, between 75-100,000 people were trapped in the LTTE-controlled Vanni in January 2009.[3] Yet other sources have placed the figure as much higher. Some have argued that GoSL deliberately underestimated these numbers in order deny adequate food and medical supplies to (at least tens of thousands), while also glossing over the massive civilian casualties which occurred during the war’s final months.

The GoSL is also falling short of expectations when it comes to the provision of death certificates and compensation. Only 64% of respondents were able to receive death certificates for their loved ones. Of the respondents who noted that someone had been killed in their family, 39% lost more than one family member. In some TSA focus group discussions, it was revealed there were instances when someone applying for a death certificate was asked to predate the date of death.

When survey respondents were asked whether the correct cause of death was listed on their family member’s death certificates, 63% or respondents stated that the correct cause of death had been denoted on the death certificate. 20% of the relevant survey respondents said that the real cause of death was not listed on the death certificate.

Regarding redress, 87% of the people chose not to approach the government for any remedy. However, amongst the 8.5% of the people that sought domestic legal remedies, 34% secured legal aid. Only 14% of the accused were subsequently interrogated. Only 10% of cases were actually filed. In this instance, the prosecution rate is 6%. Perpetrators were charged only 4% of the time. Again, the findings from TSA’s survey underscore the weaknesses and inefficiencies of the country’s institutions. Community members do not believe that the country’s institutions – as they exist today – are capable of resolving some of their most pressing concerns.

When respondents were asked if they had been given supportive counseling (if they needed it), only 13% answered positively. And, in 78% of the cases, the deceased was the principal income earner of the family. Yet, when asked about compensation, only 22% of respondents received any. Only 14% of respondents said that the assistance provided was appropriate and on a long-term basis.

These astounding numbers are a clarion call for action.

Without knowing what actually happened during those last months of fighting, true reconciliation will remain beyond Sri Lanka’s reach. The GoSL has shown little interest in uncovering all the facts about late 2008 and early 2009. The Army’s Court of Inquiry (CoI) cannot be trusted as a truly impartial investigation. After all, it is a body tasked with investigating allegations where military personnel are the alleged offenders. The LLRC’s complete exoneration of the military is also unhelpful. Besides, in its most recent progress report, the GoSL mentions that the LLRC recommendation (9.52) pertaining to death certificates and monetary compensation is “ongoing,” but this is a misleading oversimplification. Much more needs to be done.

As long as recommendations regarding wartime deaths and accountability remain incomplete, an impartial examination of past events will be urgently needed. As long as accountability is anathema to the present administration, the country’s citizens will be unable to move forward and heal as a nation.

Transitional Justice and Conclusion

The brutal end of the war in Sri Lanka gave way to the institutionalization of a “winner takes all” policy at all levels: in the government, private and non-profit sectors. Can “transitional justice” – how it is generally interpreted – apply here? Should a country simply draw a line between a brutal past and a more peaceful, democratic future? – Or should it bravely confront the past by convening a truth commission, providing reparations to survivors and victims’ relatives, or putting those responsible for human rights abuses on trial? As the Commander in Chief of the Security Forces of Sri Lanka, the President will have to investigate into how 118036 died. The Sri Lankan military, believed to be responsible for 75% of the deaths during the war’s final phases, spanning from Sept. 2008 – May 2009, are enjoying absolute impunity (if one supports the ruling family) and virtually unlimited perks under the Rajapaksa regime – are not concerned about any prosecution for most of the alleged war crimes and crimes against humanity carried out against the mostly innocent Tamil population.

Past Disappointments: Symbolic Justice is Not Justice

In many other cases around the world, a Commission of Inquiry (CoI) has been seen as one of the best way to end impunity. However in Sri Lanka, most of the presidentially-appointed CoI have often operated at the margin of the law because of a lack of political will.

A closer look into two specific CoIs in recent history the Commission of Inquiry into the Bindunuwewa Massacre and the Commission of Inquiry into 16 cases of human rights violations and killings, painfully illustrate this reality. One is entirely domestic while the other is a hybrid model.

In the case of the CoI into the Bindunuwewa Massacre, none the Commission’s findings went as far the High Court, but were turned down at the Supreme Court level. The findings of the CoI were never made public. In addition, one of the accused was rewarded with a Senior Police Officer post.

The Commission of Inquiry into the 16 cases of human rights violations and killings, did not have the desired impact to challenge impunity in Sri Lanka either. In this case, the Attorney General’s Department took on multiple identities, inevitably resulting in a conflict of interest. The CoI, by using the AG’s department to lead the interrogation of witnesses (as in the case of 17 employees of Action Against Hunger staff murdered in 2006), predisposed itself to being partial to one party.

The inherent contradictions embedded in CoI processes have resulted in these commissions failing the victims and survivors to end impunity. At the same time, these CoIs have become apparatuses of appeasement which serve principally to circumvent international criticism.

In early 2009, the international community saw a crisis coming and decided to look the other way. The results were disastrous. Created in 2010, the LLRC – Sri Lanka’s domestic solution – was designed to deflect international pressure, not to instigate meaningful change. In fact, the GoSL has disregarded both the LLRC’s interim and final recommendations. It is just another Commission that has been disregarded by those in power.

As the GoSL continues to ignore the root causes of the conflict, international actors have been far too generous with their support of the administration of Mahinda Rajapaksa. This must change. The reality is that, nearly four years since the conclusion of the country’s civil war, Sri Lanka’s ethnic conflict rages on.

Resolution 19/2 – designed to promote reconciliation and accountability – has simply not effected change. On the contrary, authoritarian gains have been consolidated, as the situation here continues to deteriorate. The present administration has had more than enough time to prove that it is serious about justice, human rights, accountability, and the pursuit of a lasting peace.

Unfortunately, Mr. Rajapaksa and his allies are not up to these challenges because the GoSL has largely ignored the recommendations prescribed in the LLRC’s Final Report – even after the passage of the US resolution on Sri Lanka. This administration is not serious about reconciliation or addressing the long-term grievances of the Tamil people.

Present Reality

Sri Lanka has flirted with impunity throughout the ethnic conflict; the end of war hasn’t had an impact on this trend. The absolute disregard for accountability has resulted in the:

- Promotion of perpetrators;

- Destabilization of the judiciary and other national institutions;

- Removal of constitutional provisions which guarantee the independence of institutions;

- Consolidation of power by the defense establishment;

- Militarization of civilian tasks;

- Promotion of impunity through continued immunity.

Absent recourse to justice at home, activists and victims’ family members are turning to the international community for truth, justice and dignity.

The Way Forward

Sri Lanka’s most recent crisis – one of human rights – has already dawned; it presents a clear and present danger to all citizens. As a result, it is imperative that the international community seize this opportunity in Geneva – to show real leadership, the kind that Mr. Rajapaksa has been unwilling to provide.

Thus far, the GoSL has failed Sri Lankan citizens, but the international community has too. Without principled leadership, there will be no justice. Without some sort of global consciousness – recognizing that human rights are meant for everyone – there can be no lasting peace.

The LLRC implementation indicators are clear, but the benchmarks have not been met. The time has come for more robust action. TSA calls on the international community to pass a strong resolution at the HRC’s 22nd session, which includes the provision for an independent international investigation for wartime atrocities committed by government forces and the LTTE. The last time international action was so clearly needed in Sri Lanka, crucial stakeholders sat idly by while tens of thousands were slaughtered in Mullaitivu.

The events that transpired in early 2009 will never be forgotten – for they are an integral part of this nation’s complicated and turbulent history. But what continues to happen in Sri Lanka – including, abductions, extrajudicial killings, sexual violence, and the state’s systemic failure to protect the fundamental rights of all its citizens – is completely unacceptable.

An International Commission of Inquiry would also be a step toward sustainable reconciliation, which requires acknowledging the human rights violations that communities and individuals have suffered and making a strong commitment to end impunity for those violations. While most people calling for reconciliation in Sri Lanka are referring to political dialogue, more meaningful reconciliation is also needed among ethnic groups – as well as between civilians and the military.

It was not long ago that the international community found itself on the wrong side of history. TSA sincerely hopes that those currently making noise in Geneva – especially those who publicly champion the pursuit of individual liberty for everyone – will not make the same mistake twice.

[1] Brian Senewiratne, “The Life of a Sri Lankan Tamil Bishop (and others) in Danger,” Salem-News.com, 7 April, 2012<http://www.salem-news.com/articles/april072012/sri-lanka-priests-bs.php>.

[2] The final phase of war refers to September 2008-May 2009.

###