Photo by Carolyn Kaster/AP, courtesy Christian Science Monitor

“They were striking at royalty, tyranny, reaction and oppression of all types, and with these they included slavery. The prejudice of race is superficially the most irrational of all prejudices . . . ” C.L.R. James

Implicit in Mitt Romney’s claim that President Obama won the election with “gifts” to people of color, women, and youth is the idea that these groups were bribed whereas people who voted for Romney did so freely out of a sense of responsibility, foresight, and concern for the future of the country. Rather than reach out to people of color by addressing their feelings of disenfranchisement and deprivation, Romney not only continues to insult and upset these groups but also fuel the highly racialized fears of the white community. He widens the gulf between social conservatives and people of color sympathetic to Republican ideals (who ended up voting for Obama) and the white women and low-income groups who voted for Romney motivated by race.

During the presidential debates, no one challenged the fact that Romney’s disdain for minorities (with their “gimme gimme” attitude) and his advocacy of “self deportation” sharply contrasted with his position on corporate handouts. Nor did the Republican Party censure Romney for his comments. For many, corporate handouts are a form of support for institutional racism, which the social safety net undermines. Perhaps Republicans mistakenly hoped that Romney’s Mexican mother would compensate for his anti-minority comments and secure both the traditional Republican and minority vote.

White voters in every demographic voted for Romney, making the 2012 election the most racially polarized in recent American history. When demographic changes finally turn the white community into a minority, race will occupy an important place in future elections. If both progressives and conservatives find ways to ignore race, there will be no honest policy-oriented discussions on institutionalized racism, especially among those with an uneasy commitment to propping it up, even when racism conflicts with self-avowed progressive values. Part of the reason for this is that discussing race is not the same as discussing racism, and it is unlikely that any future presidential candidate will directly address the issue of institutionalized racism.

The unprecedented “new voter bloc” that brought Obama into power carries much promise as a way out of this predicament.

Fixating on race and on demographic, transition-based explanations for Obama’s victory could be simplistic and misleading, however, and could be dangerous for the future if they ignore the space that this new voter bloc “occupies” in American society, one whose values, concerns, and dreams are fundamentally different and cut across racial barriers. Some people of color and many whites feel insulted when they are told that they voted for Obama only because of their race, as if their political preferences were entirely circumscribed by their racial affinities and only people of color understand and fight against racism. Even more insulting is the implication that those who vote according to color are not doing what’s good for the country (people of color being defined as “outside” of the country) but selfishly doing what’s good for themselves.

Most traditional conservatives deny the existence of racism or at least hold that it has declined as an important determinant of discrimination and inequality, but new voters’ understanding of race is far more nuanced and transcends racial boundaries. They are self-critical of the privilege they enjoy vis-à-vis other groups and will not allow their politics to be hijacked by those who wish to ignore racism. They see a common responsibility to crusade against racism and its implications for economic and social inequality, race-biased incarceration, and profiling.

The values of this new voter bloc evolved organically and spring from a concern for social justice, equality and, collective responsibility, which transcend racial barriers. Focusing on values allows us to arrive at a far more nuanced understanding of the determinants of electoral politics and the change in US race relations that occurred between the slavery era and the day of election a person of color as the president, but we will also create opportunities to address racism far more effectively. These values are reflected in the way voters think about government, economic progress, freedom, foreign policy, race, and religion.

This new voter bloc is multicultural and diverse in every conceivable sense. Voters under 30 gave Obama a 60-37 margin. Latinos voted for Obama 21-27 nationally. Romney earned only 5% of the African American vote. Unmarried women voted Obama by a 67-31 margin nationally, and race and gender distribution was pronounced in most swing states. 60% of the college educated and the least educated voted overwhelmingly Obama, but Romney gained most of the MBA votes; while doctors voted more or less evenly, a majority of the legal community voted for Obama.

While Majority of the people of color overwhelm voted Obama, we need to acknowledge the existence of a hierarchy of races and racisms arising out of different historically and contextually specific, often uneven, social, material, and power relations. At the same time, Races are capable of thinking through and beyond their respective racial affinities in terms of how they respond to social, economic, and political processes. Statistics apart, they converged to demand a different social contract with the government, one that will allow them to live with dignity. Together, these new voters proved to be a group of powerful, dedicated volunteers who “rebuked the mendacious Romney and his villainous platform to lard the rich and destroy the social safety net,” as Tim Dickinson notes.

The new voter bloc is full of “dreamers of utopian ideals” informed by a much more nuanced understanding of social issues and political agendas. Though they have yet to become an ideologically coherent bloc in terms of offering a clear path(s) for change, they seek a social contract between them and the government other than that espoused by the Republicans.

How did this new bloc arrive at this new social contract?

Further reductions in taxes and government budget surpluses will not increase production or employment, nor will economic growth automatically trickle down to the middle class. Those in lower-income brackets believe that increased taxes on the rich to maintain social safety nets is fair, because taxes are levied on the wealth low-income groups generate. Their support for big government is not hypothetical. It is born of governments as far back as the 1860s who invested in the transcontinental railway and land grant universities and passed the Homestead Act as part of the anti-slavery movement (ironically, these were early Republican Party initiatives and were opposed by the Democratic Party).

This voting majority sees that it is not “big government” but big corporations that are responsible for the decline of small businesses and that further tax reductions will not help small businesses cope with rising education and health-care costs or compete with imports.

This new voter bloc recognizes that access to health care, education, housing, and water should be made available irrespective of capacity to pay; these are basic human rights. According to the rights-based approach, the commons own all natural resources, that wealth is socially produced, and that the government must ensure the rights of the commons as well as social and environmental justice. The old right-wing dismissal of these demands as “communism” no longer carries much power because new voters consider these demands human rights and social responsibility issues rather than exclusively communist.

These new voters hold that so-called “small governments,” in collaboration with big corporations, have stolen their basic freedoms, because the corporate culture has penetrated the social fabric of their lives. They want a government that would enable them to reclaim political power from corporations, lobbyists, and the media that patronize them.

The new bloc rejects a corporate culture that values unfettered consumption despite its inequalities, injustices, and environmental degradation of global proportions. Nor do voters favor a foreign policy driven by “empire building” purely for the sake of consolidating American economic and political interests. They are opposed to war and detest its use to extend the economic and geopolitical interests of the United States. These voters are not only critical of the ideology of progress that has shaped the conventional American Dream but now dream about an America that is more responsible for universally shared values of equality and justice. Those who still hold to the conventional American Dream have become more inclusive and sober

Though new voters are also cognizant of the limits of narrow identity politics and its exploitation by some in their communities, they have not succumbed to the excesses of post-modern and post-colonial identity politics that continue to haunt society. Nor do they believe in the “clash of civilizations.” Rather, they are determined to fight against those forces that racialize civilizations to promote jingoistic nationalism and neoliberal capitalism. Over the years, these citizens have seen that access to education, health care, and housing is critical for eradicating racial inequality and they have no reason believe that corporations will provide these services..

The ideological orientation of this new political bloc is not entirely secular but is deeply influenced by a more subtle understanding of religious theologies from the perspectives of justice and responsibility. Secular vs. religious values are not helpful indicators for an understanding of voter behavior. Regardless of their faith, members of this new political bloc reject the theology of prosperity and empire building that for decades legitimized unimpeded consumption and American global hegemony.

These see serious drawbacks to the current United Nations system that consistently fails to safeguard rights, being beholden to the principle of national sovereignty, and that advocates the right to intervene in states that use state terrorism and violate the fundamental rights of their citizens. For them, the “true friends” of the United States should be judged on the basis of justice rather than on their importance to parochial American interests.

Their idea of a good society is driven by collective rather than individualistic values. They prefer an economic system than distributes resources according to people’s needs, not solely their abilities. They are wary of the private ownership of property and value a stewardship of property that allows them to care for their neighbor and the environment as they care for themselves. Their pro-life position extends beyond opposition to abortion to include access to everything people need for a better life. The inclusiveness of their theology does not leave much room for nationalism, patriotism, sexism, classism, or capitalism, because these conditions undermine the perfect equality between men and women established at Creation.

The notion of the “Kingdom of God,” evident in the theologies of this new voting bloc, suggests that those included are informed by the perspectives of justice and equality rather than those of patriotism and capitalism and are happy to subject their handed-down theologies to critical scrutiny. In other words, they detest the Americanization, racialization, and neoliberalization of theology. This is precisely why they detested Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s racist and genocidal approach to Israel and Billy Graham’s son’s support for the war in Iraq. They are vehemently opposed to Christian Zionism’s failure to recognize the oppression of Palestinians and are at the forefront of protests against the application of Sharia law to persecute Christians and violate the fundamental rights of women.

Romney’s accusations that Obama associated with world leaders who are critical of the United States reminded this new voting bloc of the biblical parables of Jesus’ friendship with those condemned by Jesus’ society. Perhaps, when Romney berated Obama for criticizing the United States in a foreign land, the new voting bloc recalled the parable where Jesus asks, “Why do you see the speck that is in your brother’s eye, but do not notice the log that is in your own eye?” The new bloc’s idea of citizenship extends beyond national boundaries, where no land is holy or enjoys privileged status unless its conduct is just and fair within and beyond its borders. Even religious progressives of good will can be color blind, because their good will does not equal anti-racism or is at least not an effective kind of anti-racism. Anti-racism requires a particular commitment to dismantling *racist* structures. It requires a conscious effort to acknowledge and come to terms with racism.

The evolution of this new political bloc is not an accident or anomaly in American society but the result of a space for critical thinking and innovation in American society made possible by decades of pedagogical endeavors of an American liberal arts education and by the ongoing renewal of religious theologies that espouse inclusive justice and responsibility beyond racial, gender, and national boundaries.

The failure by mainstream analysts of the presidential election results to consider the value orientations of this new voter bloc risks racializing society and reinforcing prejudice, stigma, and the paranoia of minority groups while sowing the seeds of future racialized conflict. People’s awareness, preferences, and struggles cannot be entirely determined by their ethnic identities; rather, these transcend racial boundaries. People have come to consider the fight against racism a common struggle rather than the sole prerogative of victims of racism.

The continuing obsession with race is not entirely about race or racism. It is often about class. It is about protecting ideology and using race as a means of deflecting antagonism away from the elite minority who control economic and political power and sustain the corporate media. This is precisely why the mainstream media spend enormous amounts of time and resources exploring the race factor in voter behavior.

I shall make a few cautionary remarks about the difficulties of dealing with the politics of identity and the politics of class to preempt circular arguments about class, race, and gender or the engagement with one at the expense of the others.

We must be cautious about the claims of “reverse racism” made under the guise of “fairness,” which are no different from those made by right-wingers through their racial politics, however much lip service they give to “inclusion.” Attitudes like this among white progressives explain why “MoveOn” wasn’t acceptable to black progressives and why Rucker had to form “Color of Change.” This situation exists because liberals and progressives have never directly addressed institutional racism and instead keep trying to talk about race as an issue of individual rights and opportunities. At times professional of color who come from privilege classes in their respective countries also contribute to such racism by blaming the “ illegal immigrants’ are unlike them as lazy and living on handouts and failing to make use of the opportunities available in the United states.

Equally important is the need to be vigilant about attempts to dismiss race- and sexuality-based inequality by saying that “identity politics” is what’s holding progressivism back and that, if only black and brown people, the GLBT community, and those pesky feminists would just focus on CLASS, all other problems would magically be solved. The “class pushers” were utterly ruthless and used the most vile language imaginable (on a progressive website!) to make personal attacks and endlessly harass people engaged in identity-based activism. The evidence shows that, all things (*including* class) being equal, the determining factor in social status, economic benefits, and political representation is race, where black and brown people are at the bottom, followed by women. We must not forget that the expanding new voter bloc owes much to the feminist movement and that those social movements work on identity-related issues. At the same time, their limitation is their failure to address class issues.

As the white American population declines and the superior status it once enjoyed erodes, some white Americans believe that they are the group that suffers the *most* racial prejudice. Loss of privilege feels like a loss of rights to those experiencing it. The conflation of lost privilege with racial marginalization gives rise to the notion of “reverse racism,” then to a feeling of persecution. Those who subscribe to such thinking see equalization as a loss of status and power and as the onset of persecution; the rebound effects are formidable, especially when checks are non-existent or powerless. Republican rhetoric has already enshrined the idea that “real” Americans are white, “others” being interlopers and parasites on the body politic. This rhetoric moves from the racist right into the progressive wing pretty quickly, which is why it’s hard to find a so-called “progressive” who actually fully supports a social welfare state or espouses an economic plan radically different from the Republicans’. Here, race meets class, each of which reproduces and entrenches the other.

The new voter bloc needs to give up its preoccupation with blue states vs. red states and flock to the red states, where they need to set up education and self-help programs for lower-class whites to raise poor-white consciousness about their own oppression and counter white racism with anti-racist education. It’s a process of de-bamboozling, as E. Franklin Frazier might say. We can’t ignore or write off those angry white people; that would make them Tea Party fodder. They are natural progressivism allies. For example, Kansans used to be at the forefront of populist organizing. Kansas didn’t go Republican until the Reagan era, but now it’s a solid red state with a growing head of racist steam.

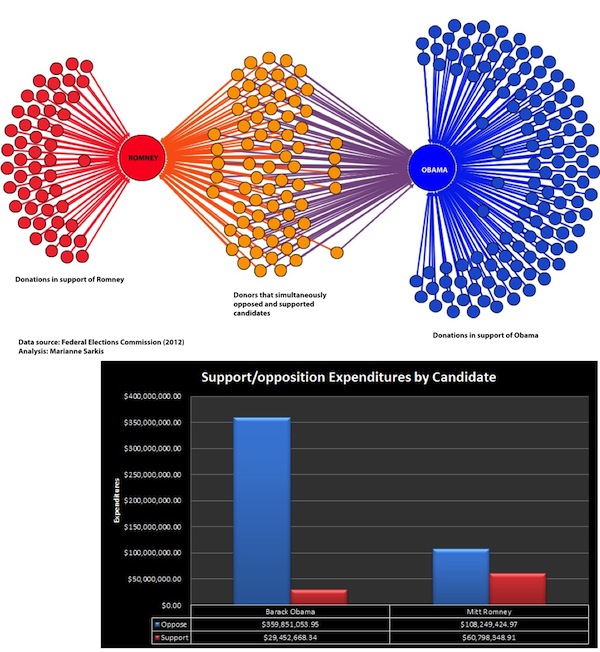

For larger image click here.

The new voter bloc is not without historical precedent. The United States is home to many social movements that transcend social, cultural, and economic differences, the most recent being the Occupy movement. Occupy attracted activists, Hispanic and Native American activists, early on. They arose spontaneously and organically, their membership springing from the communities who were most affected by the crash—black and brown communities where people were already hanging on by the skin of their teeth. The Occupy moment couldn’t sustain itself and its black activists faded from view partly because Occupy didn’t address racial issues—the ones that prevented poor black and brown people from dedicating themselves to political organizing while their white peers (with, on average, higher savings and family support) were able to continue to do so. The homeless colonized the occupiers’ physical spaces, much to the discomfort of many occupiers, because they were homeless, hungry, and no one donated food, clothing, restroom facilities, and sleeping bags as they had to the occupiers!

Despite these limitations, one cannot dismiss the Occupy movement because it embodied the normative idealism of the new voter bloc. Critics of Occupy often make the mistake of dismissing a movement that was still in its infancy and lacked the explicit support of Democrats or Republicans.

I am optimistic about the potential for these new voters to realize their dreams because their politics guided by shared values and moral convictions and on the conviction that humans, both the oppressed and the oppressors, are capable of thinking beyond, and transforming, their material and social conditions. These values are injunctions that help humans answer Tolstoy’s question, “What shall we do and how shall we live?” We must recognize the difficulties with the pluralism/relativism of values, however, because, as Seyla Benhabib suggests, the “discourse may begin with the presumption of respect, equality and reciprocity between participants,” but serious disagreements among discourse participants as to whether these attributes contribute to human dignity or to cultural imperialism can break out.

It is true that, as Sir Isaiah Berlin notes, there exists an “a priori guarantee which is the total harmony of values” because “values are an intrinsic, irremovable element of human life… and are therefore ordered in a timeless hierarchy” and are incapable of being judged “in terms of one absolute standard.” Value pluralism (and the apparent incommensurability between values) in no way means that, as Alan Bloom notes, “none is true or superior to others” or that there are no shared values or morals. The generation of new voters is not a victim of extreme notions of cultural relativism and is thus not hesitant to judge between right and wrong. Martha Nussbaum and Amartya Sen point out that even enjoying value pluralism requires a set of “core human entitlements that should be respected and implemented by the governments all nations, as bare minimum of what respect for human dignity requires.” Such a social contract is embodied in Obama’s belief “that while each of us will pursue our own individual dreams, we are an American family and we rise or fall together as one nation and as one people.”

Elections are times when the diversity of values is harmonized into a choice of the best person to guarantee core entitlements. Such harmony is informed by what Jürgen Harbamas refers to as the “discourse of morality,” which “defends a morality of equal respect and solidaristic responsibility for everybody, and such attributes are informed by a sense of equality, tolerance, inclusion, and sacrifice with respect to the fundamental necessaries for human wellbeing, and the world population that aspires to such harmony is gradually approaching 99% percent as symbolized by the new voter bloc.” The policies the new voter bloc voted for benefit all the American people, minus the 1%. People who “vote color” voted for a social contract that will bring greater good for the country, while the rest voted against the interests of the vast majority of Americans.

Whether Obama’s legacy will be the harnessing of the values of the new political bloc and helping the nation’s people to realize their dreams of a new social contract or compromise with the very forces that this new bloc is learning to resist remains to be seen. Perhaps, we could assist the process by making $5, 10, or $15 contributions towards a citizens’ movement to help the president leave the legacy he promised to leave.

(I am thankful to Dr. Kali Tal for her comments and contribution to the article)