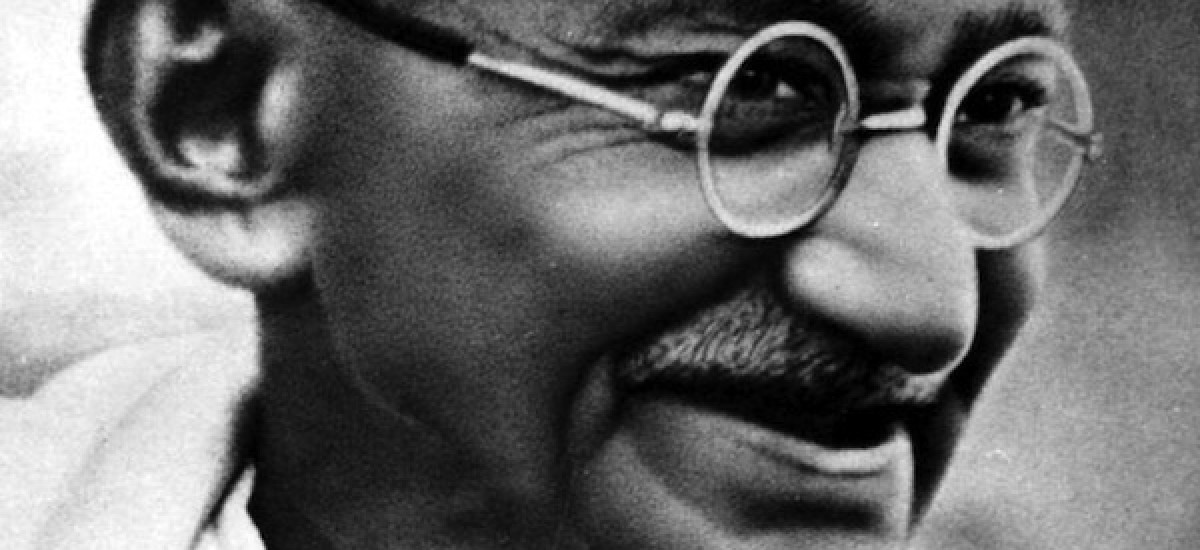

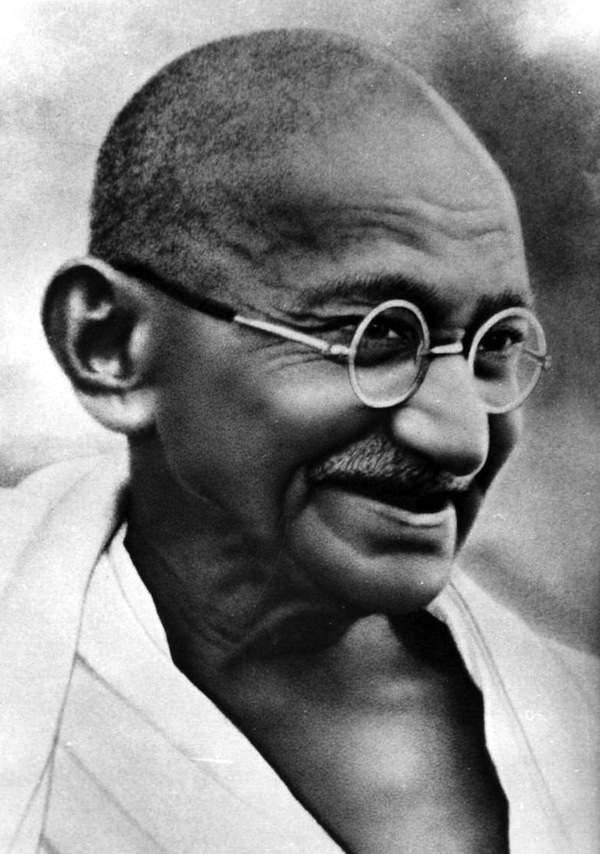

In November last year the New York Metropolitan Opera showcased its production of Gandhi- an opera by Philip Glass on Mahatma Gandhi’s struggle in South Africa. Though there were mixed reviews about Glass’s western classical rendition of the Bhaghavad Gita, the Met’s opera production was quite extraordinary. Every time the opera was performed, there was a small group of protestors from the Occupy Wall Street movement seated outside the Opera house repeating Gandhian slogans that they felt had relevance to their struggle. Since they were denied the use of loudspeakers, they just repeated what the main speaker had to say in a loud chorus. Even in those cold autumn days in a weary New York City, hard hit by the financial crisis, the Mahatma was remembered. His message will have a continuing relevance for all those who wish to change or transform society through the power of non violence.

In recent years the Mahatma has been receiving a bad press. Biographies and films have revealed that perhaps the Mahatma had a more unusual private life and a more complex family life than earlier imagined. These stories must come out and Gandhi must be judged only after we know the whole truth about him but his message to the world will continue to thrive despite his own personal shortcomings. This message which exalts non violence as a means as well as an end and which asks that politics be based on Sat or truth is a universal message that has found resonance in diverse cultures. His belief that sacrifice and moral action releases the forces of good, enabling transformation of self and society is summed up in the term satyagraha, a foundational belief of his political movement. It questioned the practice among politicians and government officials alike that politics is about manipulation and realist preoccupation with a balance of power. His ideas of non violence, of not humiliating the enemy, of social justice and of self sacrifice have inspired successive generations. It is a philosophy that values human beings and bases human interaction in a bond of mutual self respect.

My childhood was full of stories of the Mahatma, whether it was from a grand uncle who spent time in Shanthiniketan or a grandfather who was ambassador in India just after independence or from the countless intellectuals in India and Sri Lanka who were touched by the Indian National movement and came to dominate our national firmament. But it was only after I became Special Rapporteur on Violence Against Women and the UN Special Representative on Children and Armed Conflict that the words of the Mahatma, especially his intolerance for violence, have a special resonance for me. Having been to some of the major centres of conflict in the world one often yearns for the healing presence of the old man in a loin cloth walking with his staff where abuse and violence remain unchallenged.

In reading the Sri Lankan newspapers I am often struck by the casual attitude with which our commentators deal with violence. The abstract theorizing, the focus on concepts over actual suffering, the debates over technical numbers over the pain of individuals, these are disturbing trends, symbolic of a community that may have lost its sensitivity to the suffering of people.

I have seen first hand what violence during war does to women and children. There was a young boy named Moi whom I met in Northern Uganda. He was playing with his friend when the Lords Resistance Army came into his village and kidnapped both of them, while making them carry looted goods on their heads. His friend tripped and fell and was shot on the spot. Moi was beaten into submission, given drugs, trained to kill and taken to attack the very villages where his family and friends lived. He finally escaped. He was a broken boy of fifteen when I met him, awaiting a father who was scared of a combatant son and was hesitant to bring him back home. He began his conversation with me like a hard warrior but at the end he looked down and wept like the child he was.

I can tell you about Eva, a young girl of thirteen whom I met in the Democratic Republic of Congo, who was walking to school when the FDLR kidnapped her. The Hutu warriors thought she was a Tutsi child. She was kept in a state of forced nudity,, made to do to domestic work and be a sex slave to the combatants. She also escaped and was taken to the famous Panzi hospital by a kind truck driver. They found she was pregnant and when I met her she was carrying her baby who was nearly half her size. I will never forget her eyes.

We don’t have to go to Africa- here in Asia- I met Aisha in Afghanistan- a young girl whose house was bombed as part of aerial bombardment- the so called collateral damage we read about- where she lost family members. After that her school was attacked by the Taliban and some of her teachers were killed. But like Malala, from Pakistan this young girl was not giving up. She was determined to go back to school and become a teacher. I can also tell stories of young boys in internally displaced camps in Dafur who at the age of ten or twelve are recruited to be child soldiers because they are hungry and have nothing to do, or the countless numbers of children I have met who have lost an arm or a leg because they have stepped on or picked up landmines. When nations, groups and politicians decide to go to war, this is the kind of suffering that may be unleashed on the most vulnerable. These are the faces behind collateral damage, the victims of the end justifies the means, and the sticking point for the argument that we should focus on the greater good.

These stories of war make abstract theorizing about violence very difficult. When one focuses on the victim, there is almost a moral absolutism. But not everyone agrees. There have been many who feel that violence is often important and necessary. Gandhi himself was killed by one such individual. Nathiruman Godse who assassinated Gandhi was not a mad man. Ashis Nandy has written extensively on this. Godse had a different vision of India to Gandhi, a vision of an imperial India as a virile, powerful, masculine nation that would not hesitate to use force when needed or perhaps even when not needed. . Gandhi was subverting his ideal with what Asihs Nandy called his effeminate version of a non violent India. Gandhi’s model of the Indian ascetic, gentle, simple and righteous clashed with the warrior version of Godse’s India. The world is full of ideologies and individuals like Godse who value militarized societies and authoritarian leaders, who see repression as a necessary tool of governance.; who value a country’s worth by the size of its military arsenal and its people by the nature of their obedience. These states and leaders may use violence as a first resort even against their own population. Their actions are based on an image of masculinity that is at ease with the use of violence and a vision of a nation state that maximizes political and military power.

Besides ultra nationalists like Godse, there have been other leading theorists who have celebrated the use of violence. For Frantz Fanon one of Africa’s leading anti colonial thinkers, violence was an act of empowerment, of expiation and a rite of passage. In the struggle against an oppressor he felt violence was the only way to gain self respect and to fight psychological repression. Violence as a character building exercise is present in many warrior epics. The notion that violence is a rite of passage, that which makes children into adults, is present in the rituals and practices of many of our societies. These ideas may have served us well in the era of dynastic and warring societies and some may argue in early colonial struggles but do they have any relevance for building modern democracies in the age of the internet. These left over values that bring suffering to civilian populations everywhere still condition our responses to many situations. Fanon is particularly attractive to the type of young men in Sri Lanka who waged an insurrection in the north as well as two insurrections in the South of the country. They found resonance in his teachings about self respect. Yet the theorists who celebrate violence rarely think of the consequences. They often believe that violence used according to their theory will be a surgical strike. Violence never is. It is messy, often killing and destroying the most unintended victims. Those who implement these theories quickly become immune to the brutality.

When you speak to civilian victims of violence the first thing you notice is that they prefer silence. I have encountered this often- they are speechless and even if they speak they usually only narrate the before and the after. As Valentine Daniel has written in Charred Lullabies the experience of violence can never really be communicated. It is so intense that no matter how you write it up the survivor is never satisfied. The silence is also the reason why there is such a high suicide rate among some victims of violence. Veena Das’ touching portrayal of Shanthi who took her life after the Delhi riots gives you a sense of the pain that civilian victims of violence suffer.

Harvard University has also done a lot of research in post war Sierra Leone among women and children including child soldiers. Ten years after the war, there is a great deal of resilience and many people are getting on with their lives. But those who were victims of terrible violence or those who have had to perpetrate terrible acts of violence still suffer crippling symptoms and many continue to need medical intervention.

It is not only the victim who is transformed by violence it is also the perpetrator. Valentine Daniel quotes a trainer in one of the Tamil militant camps, “you can tell a new recruit from his eyes. Once he kills his eyes change. There is an innocence that is gone. They become, focused, intense, like in a trance.” That trance like state often leads to excess and if not strictly controlled by military discipline can lead to terrible acts of violence against the civilian population especially women.

These studies on violence that I have spoken about focusing on the victims make the use of force seem like an unthinkable option. But we also live in a morally complex world. There is one argument that even the greatest defenders of non violence find difficult to answer. What do you do about Adolph Hitler.? If a monster appears on the horizon, is bullying and killing those around you and is refusing to compromise- what do you do? Gandhi’s initial response would have been to deal with the root causes that created the monster in the first place. He always listened to find the reason for the violence. He would have tried to begin a dialogue, make moral appeals through fasts and other acts of civil disobedience. But what if all these attempts fail?

It is interesting to note that Gandhi never went against the British war effort in World War II. He did not support it but he did not vehemently oppose it like Subhas Chandra Bose and others. Gandhi may have argued that there is never a case for war but he did highlight Yuddhishthra’s words in the Mahabharata. After losing game after game because of loaded dice Yuddhishthra replied to the entreaties from his brothers by saying- before I put my people through a terrible war I must make sure that I have exhausted every opportunity to make peace.

I had occasion to contemplate the moral dilemmas associated with the legitimate use of force recently. Joseph Kony of the Lords Resistance Army was the one who abducted Moi and countless other children. He kidnapped children, beat them, gang raped the girls, terrorized them, injected them with drugs and sent them to kill family and friends. I was asked if I would join a campaign to request military action by the African Union against him and his commanders in Oboe in the jungles of the Central African Republic. All attempts of bringing him to a negotiating table had failed and all moral appeals had fallen on deaf ears. I was disturbed because I did not want to support military action and many of the soldiers of the LRA were children. I was also aware that countless more children in the Central African Republic, the Democratic Republic of Congo and South Sudan would be abducted and raped unless action was taken. Grace a young girl who was abducted from her high school in Northern Uganda, who had been gang raped by the LRA commanders and made to fight but who escaped, went back to school and graduated from university had become one of my closest advisors. She urged the UN to support such action to spare the children and save her friends.

Finally after hours of discussion with Ugandan military leaders who were spearheading this pan African effort we agreed to support military action. I had to compromise my Gandhian principles but the priority seemed the need to save the children. We agreed that any military action must have as its centerpiece the protection of civilians and the rescue of children. Was this a slippery slope- once we agree to military action is there no turning back? I hope not. Kony was so horrendous and so uncompromising that there was no option. Perhaps we cannot be Gandhian absolutists in practice but his spirit should guide us and I felt the emphasis on the protection of civilians could be a compromise with the Gandhian legacy. Such an emphasis would minimize the costs so evocatively portrayed by those who work with victims of violence.

I think, as more fanatical leaders emerge in different parts of the world preying on vulnerable populations, the work of the International Committee of the Red Cross, the Geneva Conventions and the ICC acquire more and more significance. Any military action no matter how justified must respect the principle of distinction- civilians must be protected and only combatants attacked and civilian objects especially schools and hospitals must be spared- and we must respect the principle of proportionality- only proportional, reasonable force should be used. We can debate the how when and why of individual cases but these principles must remain cast in stone,. If non violence is not an option, then the protection of civilians must be our guide.

With all this talk of violence and non violence- what is the relevance of the Gandhian message for us today in South Asia and Sri Lanka.. Let me begin with Indian foreign policy- now that I have the ear of the High Commissioner. For years on the global stage India has followed a low key foreign policy keeping in line with non alignment. However, I realized in recent years, that as India emerges as a global power there are great expectations. The time is opportune for India to rethink its global role, to accept its new found prominence and define a vision of the world as it would like to see the future. In crafting this vision, its Gandhian antecedents should play a prominent part. India like South Africa is well placed to combine a struggle for global equality and fair play with a struggle for human rights. At the moment we have a division of the world between the west who, despite a colonial past, see themselves as custodians of human rights even though it often smacks of double standards and others who try to combine fierce anti colonial rhetoric with the most Machiavellian of global strategies. The triumph of Gandhi was that he combined anti colonialism with a honest critique of Indian rituals and practices that debased his religion whether it was caste or child widows. The world is waiting for a leader of opinion from the third world to fight against global inequalities but who will also not tolerate human rights abuses within the third world. India, along with South Africa, is well placed to be that leader. South Block must reinvent itself and go back to reading Gandhi. It will result in the true transformation of the global polity if India is true to the vision of its founding father.

For us Sri Lankans, after a protracted north east war and two southern insurrections the words of Gandhi may seem faint and even irrelevant. All the more important that we relearn his message. Both those insurrections as violent as they were had root causes and the Sri Lankan state has to take some responsibility for not dealing with these causes and for the direct and indirect violence that resulted. During the 1990s I was a member of the Youth Commission that went around the country interviewing young people during the second JVP insurrection. The word we kept hearing was “Asardhanaya” loosely translated as unfairness, discrimination or abuse. Northern youth spoke similarly though their perceptions of what constituted injustice was different and based on their experience. And yet, those presently in control of the state do not seem to have learnt the lesson- that discrimination, abuse of power, arbitrary use of force and blatant thuggery have consequences, that violence begets violence- as Gandhi would have said. If rulers ruled in an inclusive way, stating they will govern in a manner so that no-one would feel so excluded as to want to take up arms, then we may indeed escape the cycle of violence. That would be the real path way to reconciliation. A situation where everyone feels ownership of the state that represents them. A lack of respect for diversity, impunity for grave crimes, tolerance of violence and triumphantalism will only polarize an already deeply divided polity. Generosity toward minorities and dedication to the rule of law is the need of the hour. Our present leaders may wish to look to Gandhi and other such leaders on how we can establish a society based on mutual self respect in the aftermath of a terrible war. But my sense is that we are not there yet and that we have not learnt the bitter lessons of the past.

It is not only the state that must turn inward. Even if there is discrimination, repression and abuse in a society, the nature of the resistance is often as important as the cause itself. When violence began to dominate Sri Lankan Tamil politics, we lost our way and the path to Mullaivaikkal was inevitable. And what did we gain? Jaffna that once had the highest physical quality of life index after Colombo now has one of the worst. More than half the population has fled to other parts of the country or gone overseas. A large part of the population is psychologically traumatized by what they have seen over the period of the war. Large plots of land have been occupied by the state or the military. I hope at least the leaders of the Tamil community and Tamil politicians have learnt this lesson. When they turned their backs on Gandhi, they brought untold suffering to their people. Tamil grievances are still to be addressed but the politics of gaining recognition must be inspired by leaders such as Gandhi. Tamil political leaders often used non violence to generate support in their areas but when it came to the Sinhalese they only dealt with the main politicians. The time may be ripe for them to reach out to the Sinhalese people themselves as well as their social and religious leaders to forge an inclusive politics that is based on a moral vision of what is right and just. I have great faith in the young people of Sri Lanka who have been spared the baggage that many of us carry. It is time to reach out to them and hope that they will lead the way to a better future.

Finally I will confess that supporting the Mahatma at all times is not easy. I went to Gaza right after Operation Cast Lead by the Israeli Defense Forces. The destruction was monumental. Children kept drawing helicopters and tanks attacking houses and people. I was with a Palestinian youth group where with rhetorical flourish after rhetorical flourish they spoke of vengeance, of becoming martyrs for the cause of vindicating what was done to them. I asked them whether they ever thought of non violence. They were incredulous. I told them the story of Mahatma Gandhi. They shouted me down. They would have none of it. Some even left the room saying I was insulting the martyrs that had died for the cause. In a post September 11th world the teachings of the Mahatma sometime seem quaint and out of place.

Then I think of the old monk I met at the Schwedegon Buddhist Pagoda in Myanmar some years ago. Being Sri Lankan he took me into a special private room to worship the emerald Buddha. I was honoured by that privilege. He told me that he was brought up in India and that he was a follower of Mahatma Gandhi and that he often took part in civil disobedience and protests against the government at great risk to himself and his fellow priests. He then complained that the UN was doing nothing for Myanmar. I gave him a bureaucratic response not knowing what to say. Then he said “even if you do not help us we will be free, Burma will be free…non violence will prevail…” I thought he was a dreamer then but now often wonder what he must be doing and feeling.

Thank you.

###

Speech delivered at the Mahatma Gandhi Oration, 30 October 2012, at the Indian Cultural Centre, Colombo.