Titus Thotawatte, 1929 – 2011

Emmanuel Titus de Silva, better known as Titus Thotawatte, was the finest editor in the six decades long history of the Lankan cinema. He was also a great assimilator and remixer – a veritable ‘builder of bridges’ across cultures, media genres and generations.

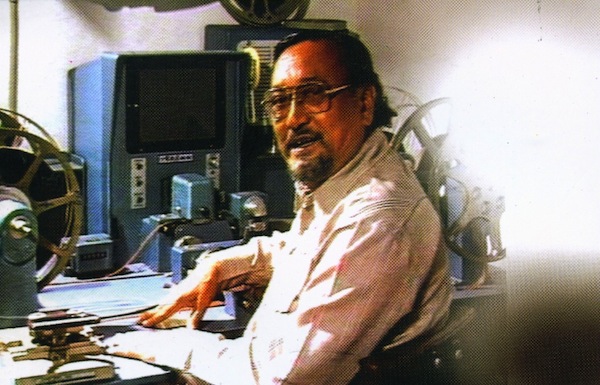

Titus straddled the distinctive spheres of cinema and television with a technical dexterity and creativity rarely seen in either one. Both spheres involve playing with sound and pictures, but at different levels of scale, texture and ambition. Having excelled in the craft of making movies in the 1960s and 1970s, Titus successfully switched to television in the 1980s and 1990s. There, he again blazed his own trail in Sri Lanka’s nascent television industry. As a result, my generation remembers him for his television legacy whereas my patents’ generation recall more of his cinematic accomplishments.

Titus left an indelible mark in the history of moving images. The unifying thread that continued from 16mm and 35mm formats in the cine world to U-matic and Betacam of the TV world was his formidable genius for story telling. He was a magician who played endless tricks with our eyes and mind. We encored for more.

Titus de Silva, as he was then known, was a member of the ‘three musketeers’ who left the Ceylon Government Film Unit (GFU) in the mid 1950s to take their chances in making their own films. The other two were director Lester James Peries and cinematographer Willie Blake. Lester recalls Titus as “an extraordinarily talented but refreshingly undisciplined character” who had been shunned from department to department at GFU “as he was by nature a somewhat disruptive force”.

The trio would go on to make Rekava (Line of Destiny, 1956) – and make history. In his biography by A J Gunawardana, Lester recalls how they were full of self-confidence — “cocky as hell” — and determined to overcome the artificiality of studio sets. “We were revolutionaries, shooting our enemies with the camera, and set on changing the course of Sinhala film. In our ignorance, we were blissfully unaware of the hazards ahead – seemingly insurmountable problems we had to face, problems that no book on film-making can ever tell you about!”

Titus Thotawatte – photo courtesy biography by Nuwan Nayanajith Kumara

In the star-obsessed world of cinema, the technical craftsmen who work the real magic rarely get the credit or popularity they deserve. Editors, in particular, must perform a delicate balancing task – between the director, who has his own vision of how a story should be told, and the audience that fully expects to be lulled into suspending their disbelief. Good editors distinguish themselves as much for what they include (and how) as for what they leave on the ‘cutting room floor’…

The tango between Lester and Titus worked well, both in the documentaries they made while at GFU, and the two feature films they did afterwards: Rekava was followed by Sandeshaya (The Message, 1960).

They also became close friends. At his own expense, Titus accompanied Lester to London where they re-edited and sub-titled Rekava (into French) for screening at the Cannes festival of 1957. As Lester recalls with gratitude, “Titus was a great source of moral and technical strength to me; his presence was invaluable during sub-titling of the film”.

In all, Titus edited a total of 25 feature films, nine of which he also directed. The cinematic trail that started with Rekava in 1956 continued till Handaya in 1979. While most were in black and white, typical of the era, Titus also edited the first full length colour feature film made in Sri Lanka: Ran Muthu Duwa (1962).

His dexterity and versatility in editing and making films were such that his creations are incomparable among themselves. In the popular consciousness, however, Titus will be remembered the most for his last feature film Handaya, which he both directed and edited. Ostensibly labelled as a children’s film, it reached out and touched the child in all of us (from 8 to 80, as the film’s promotional line said). It was an upbeat story of a group of children and a pony – powerful visual metaphors for the human spirit triumphing in a harsh urban reality that has only exacerbated in the three decades since the film’s creation.

Handaya swept the local film awards at the Saravaviya, OCIC and Presidential film awards for 1979/1980. It also won the Grand Prix at the International Children and Youth Film Festival in Giffoni, Italy, in 1980. That a black and white, low-budget film outcompeted colour films from around the world was impressive enough, but the festival jury had watched the film without English subtitles was testimony to Titus’s ability to create cine-magic that transcended language.

Despite the accolades from near and afar, a sequel to Handaya was scripted but never made: the award-winning director just couldn’t raise the money! This and other might-have-beens are revealed in the insightful biography written by journalist Nuwan Nayanajith Kumara. Had he been born in a country with a more advanced film industry with greater access to capital, the biographer speculates, Titus could have become another Steven Spielberg or Walt Disney.

Titus Thotawatte was indeed the closest we had to a Disney. As the pioneer in language versioning at Rupavahini from its early days in 1982, he not only voice dubbed some of the world’s most popular cartoon animations and classical dramas, but localised them so cleverly that some stories felt better than the originals! Working long hours with basic facilities but abundant talent, Titus once again sprinkled his ‘pixie dust’ on everything he came across in the formative years of national television.

In May 2002, when veteran broadcaster (and good friend) H M Gunasekera passed away, I called him the personification of the famous cartoon character Tintin. I never associated Titus personally, but having grown up in the indigenised cartoon universe that he created, I feel as if I have known him for long. Therefore, I hope Titus won’t mind my looking for a cartoon analogy for himself.

I don’t have to look very far. According to his loyal colleagues (and biographer), Titus was a good-hearted and jovial man with a quick temper and scathing vocabulary. It wasn’t easy working with him. That sounds a bit like the inimitable Captain Haddock, the retired merchant sailor who was Tintin’s most dependable human companion. Haddock had a unique collection of expletives and insults, providing some counterbalance to the exceedingly polite Tintin. Yet beneath the veneer of gruffness, Haddock was kind and generous. It was their complementarity that livened up the globally popular stories, now a Hollywood movie by Steven Spielberg awaiting December release.

Perhaps that’s too simplistic an analogy for Titus. From all accounts, he was a brilliantly creative and multi-layered personality who embodied parts of Dr Doolittle (Dosthara Honda Hitha), Top Cat (Pissu Poosa), Bugs Bunny (Haa Haa Hari Haawa) and a myriad other characters that he rendered so well into Sinhala that some of my peers in Sri Lanka’s first television generation had no idea of their ‘foreign’ origins…

Titus was also a ‘Gulliver’ whose restlessly imaginative mind traversed space and time, even when he was confined to one place during the last dozen years of his life.

A pity he spent too much time in Lilliput…

###

After years of cartoon watching, Nalaka Gunawardene is hopelessly confused about reality and make-belief. He blogs on moving images and popular culture at http://nalakagunawardene.com, where this tribute first appeared on the day of Thotawatte’s funeral.