Last week, I attended a seminar conducted by the Colombo-based Marga Institute, a think tank devoted to studying and influencing human development in Sri Lanka. Marga is in the process of putting together a review of the UN Secretary General’s advisory panel report on Sri Lanka (the well-known Darusman Report), which will analyze several aspects of this document, including its legal credibility; the manner in which it makes its allegations and narrates the series of events that made up the final stages of the war; the recommendations of the report; and, very importantly, the impact all of this will have on the reconciliation process in Sri Lanka, via accountability and restorative justice. The seminar itself was to elaborate on the thinking behind the review, discuss the draft, and possibly include the conclusions of such discussions in the final review.

The seminar was therefore conducted in a series of panel discussions, each looking at a different aspect of the Darusman Report, and each made up of experts in that area. I was there mostly because I was part of the panel looking at the allegations made against the Sri Lankan Armed Forces in their conduct of the final operations to defeat the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam. With me was Arjuna Gunawardene, a defence analyst, writer, and expert in suicide terrorism, and the session was moderated by Asoka Gunawardene of the Marga Institute. While this session began with presentations by both Arjuna and I, it focused around a series of key questions that we had been asked to examine. What I’m now going to do in this blog post is present our view in the form of a Q&A that will include our presentations and the questions that were subsequently put to us by the moderator and the other participants.

In the Darusman Panel’s account of the last stages of the war, and the events that lead to the allegations of war crimes, is the panel’s account complete, or if not complete, adequate, and has it been able to access all sources of information that are essential for coming to fair and just conclusions concerning the events and actions?

The account is certainly not complete, nor adequate, if it is taken as an objective narration of the events. But I believe it isn’t meant to be so, and is a document comparable to a policeman’s request for a search warrant, which sets out to show sufficient suspicion of guilt. However, since the report has been released to the public and is being treated and used as a historical account, its biases and subjectivity must be brought into account.

To be fair and objective, the panel would have needed to interview combatants as well as eyewitnesses to ascertain motive for some of the acts which are alleged to be criminal. It would need to examine the actual scenes of the crimes instead of merely examining photographs. Therefore, in Part I of the report (Mandate, Composition, & Programme of Work), Section D (Interaction with the GoSL), paragraph 22, the panel says that visiting Sri Lanka “was not essential to its work”, thereby confirming that an actual investigation was never its intention.

In spite of this statement, the laying out of the events takes the form of a narrative or historical account, suggesting that it is fact rather than allegation. Footnotes are given to previously documented statements or reports, but there isn’t any indication of where the other information came from. It is, of course, understandable that witnesses cannot be named at this stage, but it is still necessary to indicate what the capacity of an eyewitness was. Was he or she a civilian IDP, an NGO worker, or a journalist? Often, allegations of the use of artillery, cluster munitions, white phosphorous, etc are made without any indication of the source, or what expertise that source may or may not have in determining whether these were indeed the weapons and munitions used.

This is compounded further in the Executive Summary of the report which, for example says in the section Allegations Found Credible by the Panel, “Some of those who were separated were summarily executed, and some of the women may have been raped. Others disappeared, as recounted by their wives and relatives during the LLRC hearings.” By lumping together the unattributed allegations of rape and execution with those made by identified witnesses before the LLRC, the report gives the rape and execution allegations a higher credence which they may not deserve. There are many such similar examples, and it is a strategy subsequently used by the Channel 4 “documentary” Sri Lanka’s Killing Fields, in which footage of identifiable Sri Lankan soldiers committing shocking but non-criminal activities is shown alongside footage of unidentified persons committing obviously criminal acts, thereby implying that all the acts shown are criminal ones committed by identifiable SL Army personnel.

Has the panel examined all possible explanations and interpretations of the events and actions before coming to its conclusions?

The report analyzes certain events and draws conclusions which often do not take into account factors that the report itself acknowledges elsewhere. While legally, the actions of the Tigers may not have any effect on the culpability of the Government of Sri Lanka or the SL Army, in a report which must examine motive, this refusal to examine the impact of Tiger actions on those of the GoSL and the SL Army is indicative of an unwillingness to acknowledge the possibility that there might be motives other than those alleged by the report.

For instance, in the Executive Summary’s conclusion to the allegations, it says, “the Panel found credible allegations that comprise five core categories of potential serious violations committed by the Government of Sri Lanka: (i) killing of civilians through widespread shelling; (ii) shelling of hospitals and humanitarian objects; (iii)denial of humanitarian assistance; (iv) human rights violations suffered by victims and survivors of the conflict, including both IDPs and suspected LTTE cadre; and (v) human rights violations outside the conflict zone, including against the media and other critics of the Government.”

It then goes on to say, “The Panel’s determination of credible allegations against the LTTE associated with the final stages of the war reveal six core categories of potential serious violations: (i) using civilians as a human buffer; (ii) killing civilians attempting to flee LTTE control; (iii)using military equipment in the proximity of civilians; (iv) forced recruitment of children; (v)forced labour; and (vi) killing of civilians through suicide attacks.”

However, there is no attempt to acknowledge the fact that allegations against the Tiger such as “(i) using civilians as a human buffer” and “(iii) using military equipment in the proximity of civilians” would contribute hugely to “(i) killing of civilians through widespread shelling” and “(ii) shelling of hospitals and humanitarian objects”, as the SL Army is alleged to have done.

It is on very rare occasions that the Tiger actions are specifically mentioned in relation to SL Army action. For instance in paragraph 79 of the report it says, “During the ninth and tenth convoys, shells fell 200 metres from the road, and both the SLA and LTTE were using the cover of the convoys to advance their military positions,” and then goes on to say in paragraph 86, “The LTTE did fire artillery from approximately 500 metres away as well as from further back in the NFZ,” without acknowledging that it was this very tendency of the Tigers to fire artillery and other weapons from close proximity to the civilians that was bringing in counter-battery fire 200 metres away.

500 metres is not a huge distance in such a restricted battle space, and it is very possible for even a single shell, or two or three, that could have devastating effect on concentrated civilians, to fall 500 metres off target. One or two shells could kill and injure a hundred civilians, and seem to indicate deliberate intent even when it isn’t so intended.

The strategies and actions of the LTTE – doesn’t the Panel’s account cover most of the LTTE’s actions which were observed during the war – use of civilians as a buffer, shooting of civilians who were escaping, conscription of civilians and pushing them to the front lines as cannon fodder, fortifying the no-fire zones, using mobile artillery shooting from proximity of hospitals?

It does, but not in a manner that indicates cause and effect. Again, we can assume that the Secretary General, for whom the report is said to be intended, is intelligent and experienced enough to draw the appropriate conclusions. However, it comes across as quite strange that a panel that allows itself to make the most tenuous of conclusions in certain areas, does not think it equally fitting to point out this factor even in passing. It is quite clear that the only reason there is even this solitary description of the Tiger artillery in action 500 metres from the civilians is because it was observed by a senior UN military officer, and that similar observations by IDPs and other less expert witnesses have been ignored. In contrast, the number of detailed descriptions of SL Army activities indicates that there was no such restriction in culling statements of non-expert witnesses.

Why does the report ignore its own evidence of the LTTE’s actions in integrating the civilians into the battlefield and its consequences for the options available to the SL Army?

In looking at the specific dismissal of Tiger military action in close proximity to hospitals and civilians, this must be viewed in the same way as the entire report. Its purpose is to show the UNSG that the GoSL and the SL military look guilty enough for further in-depth investigation. So to therefore create doubt about that guilt by pointing to Tiger violations as a probable cause that might have directly contributed to the civilian casualties would be counterproductive.

It is for that reason that the report refers to the SL Army’s attempts to help civilians escape as actions by “individuals”, rather than as part of a plan, suggesting that these “individuals” were acting alone and in contravention of the actual policy, which was to kill as many civilians as possible. Similarly, using phrases like “human buffers” instead of “human shields” reduces the perceived severity of the Tiger violations, thereby keeping the focus on allegations against the SL Army.

The Panel had no access to the Sri Lankan Government’s account of events, but does not openly admit the lacuna and state its implications. In the absence of a full account from the GOSL it falls back on a few statements of the Government which claimed that the war was a humanitarian operation directed at rescuing the Vanni population from the control of the LTTE with zero civilian casualties and dismisses these claims.

If the report is taken merely as an advisory to the UNSG, it is probably fair to say that the panel felt it didn’t have to elaborate on the implications of the GoSL’s non-cooperation, as the UNSG would be quite aware of these. However, as I earlier said, as a public statement, these need to be explained.

The few statements from the GoSL that the report quotes (none of which are addressed to the panel, and most of which were made during the war and in its immediate aftermath) have also been taken as statements of fact, and not looked at in the context of political rhetoric and propaganda. The “humanitarian operation” and “hostage rescue operation” claims, which the report tries to use to invalidate the actions taken by the SL military have as much credence as the United States calling the invasion of Iraq “Operation Iraqi Freedom”. To take these literally would be to display incredible naivete at best, or a intent to use things out of context to prove a point. Actions must be compared against an objective model, and not the claims of one party or another.

How should the Panel have dealt with its inability to gain access to the GOSL’s full account of what happened?

A: The panel could also have corresponded with the GoSL in a more detailed manner and asked specific questions pertaining to specific incidents. If these had been ignored by the GoSL, it would have been possible for the panel to at least claim to have attempted to get the full picture. But as I said before, such an advisory report, which isn’t supposed to be an investigation has no obligation to be that fair.

The report concludes that the GoSL denied adequate supplies of food and medicine to the civilian population, there was deliberate shelling of hospitals and civilians and that there is a credible allegation that the GOSL committed a crime against humanity by actions calculated to bring about the destruction of a significant part of the civilian population.

I’ll not comment too much on the allegations about misrepresenting the number of civilians in the area, since I believe a separate panel will look into the IDP issues, but I think it’s fair to say that there was a lot of confusion and contradictory claims by various organizations. Coupled with the movement of large numbers of civilians right across the Wanni, I don’t think it’s hard to conclude that the GoSL simply got the numbers wrong.

On the subject of deliberate shelling of civilians and hospitals, again it is impossible from the report to ascertain how this conclusion of intent was arrived at. As I said earlier, the movement of Tiger units and artillery within the NFZs and in close proximity to the civilians would indicate that even with the civilians best interests in mind, it would be very hard to avoid casualties amongst them, simply because of the restricted battle space. The report focuses only on civilian casualties and gives no information of Tiger units coming under fire in close proximity to the civilians, something which many eyewitnesses have admitted to seeing themselves. Leaving that out of the narrative suggests that there was very little or no military activity in the areas around the civilians, and that therefore there was no reason for any shelling by the SL Army.

The facts however are different, and a lot of UAV footage as well as SL military statements point to the fact that the Tiger units were actively fortifying and defending terrain even in the NFZs, often relocating high value weapons and ordnance within the NFZs and in close proximity to the civilians, and that far from the civilians and hospitals being easily recognizable islands in a sea of calm, they were right in the middle of an intensely contested battlefield.

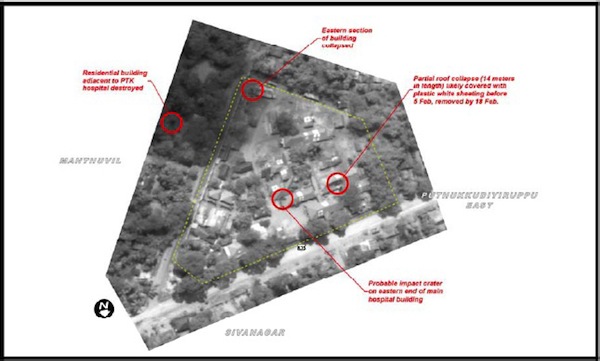

PTK Hospital (image 3.1 of Annex 3 of the Darusman Report)

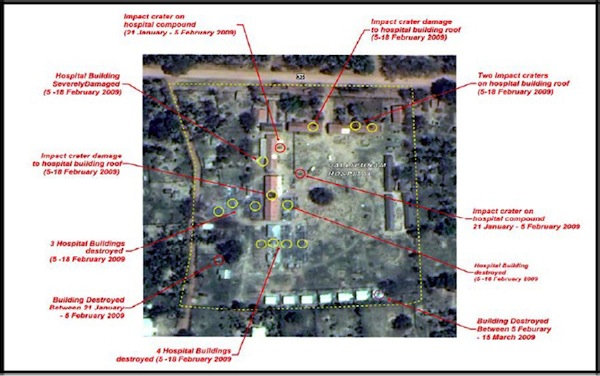

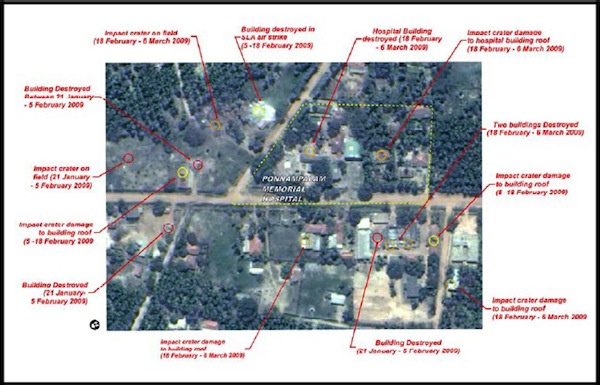

The report also carries a number of satellite images of some of the damaged hospitals, with individual holes marked as shell craters. The pictures themselves don’t indicate who fired the shells, what caliber they are, or which direction they came from; and it is left to the narrative to explain this. Several of these images have been cropped very tightly to show only the hospital grounds, and in the case of the PTK Hospital (Image 3.3 in Annex 3), it has been cropped to precisely follow the contours of the pentagon-shaped grounds. Such cropping makes it impossible to see what might have been in immediate proximity to the hospital, or to ascertain by counting shell craters, whether a larger percentage of the rounds were aimed at targets in the immediate vicinity, and not in fact at the hospital itself.

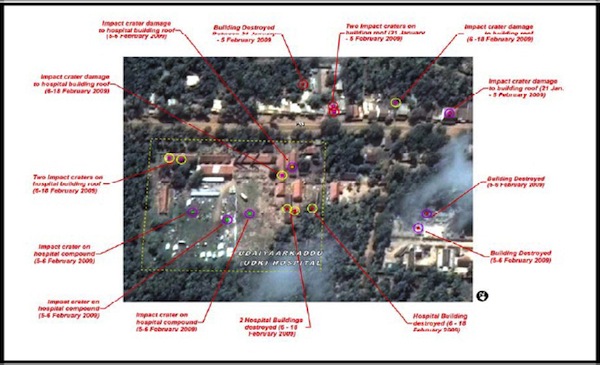

In spite of this attempt to be selective in what they present, it is possible to see that in five of the six images (the Udaiyaarkaddu, Vallipunam, PTK, Ponnampalam, and Puttumatalan hospitals) a major road or highway ran alongside the hospitals and, very likely were routes of movement for Tiger units.

Udaiyaarkaddu Hospital (image 3.1 in Annex 3 of the Darusman Report)

It is also clear in Image 3.1 of the Udaiyaarkaddu Hospital, that of the 17 craters marked, as many as seven have landed to the west and southwest of the hospital, many targeting buildings on the far side of the A35 Highway. It is possible that an examination of a more complete image would show impacts even further away, indicating that the hospital itself wasn’t the target, and simply unfortunate collateral damage.

Vallipunam Hospital (image 3.2 in Annex 3 of the Darusman Report)

Ponnampalam Hospital (image 3.4 of Annex 3 of the Darusman Report)

Image 3.4, of the Ponnambalam Hospital shows 13 instances of damage by what is claimed as artillery fire, and one SLAF airstrike. Of these 14 instances, only two occur within the hospital premises, and most hits are recorded to the north and northeast of the hospital. The date of the airstrike isn’t exact, but is indicated as prior to 18 February. The 13 artillery hits are dated between late January and early March 2009, indicating a hit every 3-4 days, which is hardly the sort of strike rate compatible with an allegation of deliberate targeting.

In paragraph 91, the report claims that the PTK Hospital was hit every day by multiple-barrel rockets (MBRL) and artillery fire between 29 January and 4 February and suffered nine hits, which is not more than one or, at most, two a day, which is more in line with accidental hits rather than deliberate ones. It is also very unlikely that the allegation of MBRL fire is true as this is a saturation weapon which doesn’t fire single rounds. In addition, Image 3.3 of the PTK Hospital, only shows three areas of impact, and it is unlikely that all nine claimed hits impacted so precisely in three areas.

In paragraph 94, the report says that the Tigers fired artillery from the vicinity of the PTK Hospital, but that they did not use the hospital for military purposes, clearly not seeing the incongruity of that statement. It also goes on to say that the Tigers used the hospital for military purposes after it had been evacuated.

There are more examples, but I think you get the picture, even without looking at the disparity between what the Darusman Report claims happened and that reported at the time by Tiger mouthpieces such as Tamilnet, which indicate the damage and casualties in the hospital premises were far less severe, and more in line with the damage visible in the satellite images.

The report also attempts to use dramatic prose to paint a picture and lend emotion to a narrative that often takes a tangential path to that of the actual dry facts. Even when describing the shelling of the UN personnel of Convoy 11 in late January 2009, the report calls their overnight camp at Susanthipuram Junction, on the A35, as a “UN hub”, suggesting that it was some sort of permanent facility, when it was nothing of the sort. The narrative uses words like “pounded” and “heavy” when describing even the landing of just several shells, and this seems intended to use a tone of voice to suggest prolonged and deliberate shelling rather than random ones.

If one examines the fighting both in northwest SL, the central Wanni west of the A9 Highway, and even in the Eastern Province, there is no indication of any such deliberate targeting of civilians in those areas. The civilian casualties mounted only after Kilinochchi fell in January 2009 and the SL Army divisions crossed the A9. This rather obvious aspect, which would be in contrast to the allegations is never commented on by the report. The fact is the casualties increased as the battle space shrank dramatically, and the Tigers started to replace their own casualties with conscripted civilians and increasingly used slave labour on the front lines.

When considering all of this, it’s clear there are major flaws in the Panel’s account. The dubious manner in which the Panel exceeds its mandate which does not include fact finding and investigation. The tendentious nature of presenting allegations as the true account of what happened. The lack of transparency in not disclosing the sources of information. Excluding government actions which are not consistent with the Panel’s interpretation. The untenable basis on which the charge of extermination is based. The refusal to examine other credible explanations relating to civilian casualties. The confusing speculation leading to the high estimate of civilian deaths. The significant omissions in the report that could provide a different explanation of the government’s strategy and actions.

As pointed out before, the purpose of the report is to give the UNSG enough ammunition to take whatever fresh action is possible to him. It is not supposed to be the results of an investigation, nor is it supposed to be an indictment that can stand up in a court of law. It is simply put together to show enough credible allegations that serious war crimes and crimes against humanity have been committed by the GoSL, and to overcome the resistance of the latter and its international allies to an independent investigation.

The Panel’s account of the government strategy as being the destruction of the LTTE along with the extermination of a considerable section of the Tamil population. Would it be correct to say that from the information given by the panel, the LTTE’s strategy was to integrate the civilians into the battlefield and as far as possible, obliterate the distinction between the combatant and non-combatant, military and non-military objects?

Certainly. It has always been the strategy of the Tigers, and all guerrilla/terrorist organisations. The fact that the Tigers had gradually transformed itself into a conventional force doesn’t change that. In the last stages of the war, particularly in 2009, after its units had been broken in battles like Aanandapuram, the Tigers were forced to revert back to a guerrilla force; unfortunately, they didn’t have the terrain area to maneuver in and had to instead maneuver amongst the civilians.

The Government’s and Army’s handling of the civilian situation regarding the necessity of separating civilians from the LTTE; what were the options; what were the efforts made?

This is hard to answer without being privy to the actual strategy and policy discussions the GoSL and its military would have obviously had. On the face of it, it is clear that the SL military did try to separate the civilians from the combatants, and that is a basic in modern warfare, particularly since most wars in the second half of the 20th century have been unconventional. In the few occasions where we have seen conventional warfare, there has been a tendency to revert to the unconventional when defeated in conventional battle; case in point, Iraq, where a conventional uniformed army reverted to the guerrilla/terrorist role with the onset of defeat. All of this has made it policy to separate civilians from combatants as quickly as possible in order to fix and destroy the combatants unhindered.

If the GoSL instead had a different policy, namely of lumping everyone together and killing them all, it is hard to see why there was no indication of that policy in either the East nor in the Northwest, and not even in the fighting west of the A9. The SL military also dropped leaflets telling the civilians to come over to the GoSL side; an act that the report states, albeit not in the form of an acknowledgment; something that would be counterproductive to a policy of murder.

It is possible to say that perhaps the GoSL didn’t try hard enough in the offensive east to Kilinochchi in late 2008, but perhaps the magnitude of what was to come wasn’t something they thought was possible. Perhaps they didn’t believe that such large numbers of civilians would accompany the Tigers.

It is also possible that the SL Army’s inability to pin down large Tiger units in the east and even the western Wanni, made them preoccupied with maneuver warfare where speed was of the essence to cut off Tiger units from the A9 while keeping others pinned down on the Jaffna Peninsula, holding the diversionary “ National Front” on the Muhamalai-Nagarkovil line. Until the loss of the A9 highway, Tiger units were fairly cohesive, and fighting conventionally, and the SL Army would have been concentrating on that problem. It was after Kilinochchi, Aanandapuram, etc that the Tigers collapsed and started to use the civilians so actively.

On the two main war crimes mentioned in the report — civilan casualties, were they intentional? Shelling of hospitals, what were the circumstances? Were they avoidable, indiscriminate, unjustifiable?

It seems very difficult to find instances of either deliberate killing by the SL military, or even reckless endangerment. They were fighting in difficult conditions against an enemy who was actively using civilians as cannon fodder. Many of these conscripts were killed in droves, but they cannot be said to be civilians if they were armed and manning fortifications. I would put down the shelling of hospitals as purely accidental. The damage presented is just not consistent with deliberate targeting.

I think anything in war is avoidable if one is willing to stop fighting. But the purpose of war is to achieve certain objectives, and often those do not permit a pause in the hostilities so that every single blurred line may be sorted out.

Government’s statements that they had stopped the use of heavy artillery and that they were maintaining the zero civilian casualty objective?

As said earlier, many statements by governments in wartime are merely for purpose of propaganda or for political reasons. It is naïve and willfully ignorant to take these as literal and expect the battlefield realities to conform to these statements. I’m sure the GoSL meant well with its “zero civilian deaths policy’, but I’m yet to see a policy that could stop an RPG-7.

The statement that the SL military had decided to cease the use of heavy weapons seems to have been a short-termed decision. It is highly likely that either this was mere propaganda meant to demoralize the Tiger supporters by suggesting that defeat was imminent, or that the GoSL actually thought the Tigers were closer to defeat than they actually were. If the latter, the GoSL would have reverted back to the use of such weapons. However, it’s clear that towards the latter stages, the use of fixed wing aircraft was severely curtailed. Even the report hasn’t many descriptions of airstrikes.

The Panel does not give us any estimate of the numbers engaged as combatants on both sides to gain some understanding of the scale and intensity of the fighting. What is your estimate of the number of combatants engaged on both sides and the combatant casualties?

The report does make an approximate estimation of the numbers. In paragraph 62, the report names the SL Army units as six divisions (the 53rd, 55th, 56th, 57th, 58th, and 59th). While they are right that there were six division-sized units in action in the Wanni after the fall of Kilinochchi, in reality the units were the 57th, 58th, and 59th Divisions and Task Forces 2, 3, and 4; which would be approximately 60,000 troops. The 53rd and 55th Divisions which had been on the Nagarkovil-Muhamalai line until the end of 2008 subsequently broke through, and while the 53rd secured Elephant Pass, the 55th joined the battle on the mainland in January, adding around 10,000 troops.

The Tigers were thought to have between 10-15,000 troops at the fall of Kilinochchi, but not all of them were of the same fighting standard, and perhaps half that number survived to the final stages. The report estimates, in paragraph 66, the Tiger fighting strength at 5,000 by April 2009.

Given the conditions in the last stages where the LTTE had tried to integrate the civilians into the battlefield and as far as possible obliterate the distinction between the combatant and non-combatant, military and non-military objective what do you think were the options available to the army?

Like I said before, one option open to the SL military was to slow down and use probing attacks to get the civilians out. However, the use of artillery would still have been necessary to keep the Tigers pinned down and prevent a breakout. Personally I see very little options open to the GoSL if they wished to both ensure that the Tigers didn’t escape, while still minimizing civilian casualties.

From a purely military perspective, it’s possible to say that a slowing down and a laying siege might have been effective. However, given the conditions that the civilians were in, and the intense international pressure to cease hostilities, such a slowing down would not have been practical if victory was to be achieved.

How would you comment on the Panel’s estimate of civilian casualties.

In paragraph 137, the report says that “Two years after the end of the war, there is still no reliable figure for civilian deaths, but multiple sources of information indicate that a range of up to 40,000 civilian deaths cannot be ruled out at this stage,” which is a very ambiguous statement, and without any explanation of why other estimates quoted in the same paragraph have been rejected. So I guess that even figures as low as 2,800 (the UNHCHR figure) similarly cannot be ruled out on the same grounds.

The Marga Institute review is scheduled to be released on 5th August 2011.