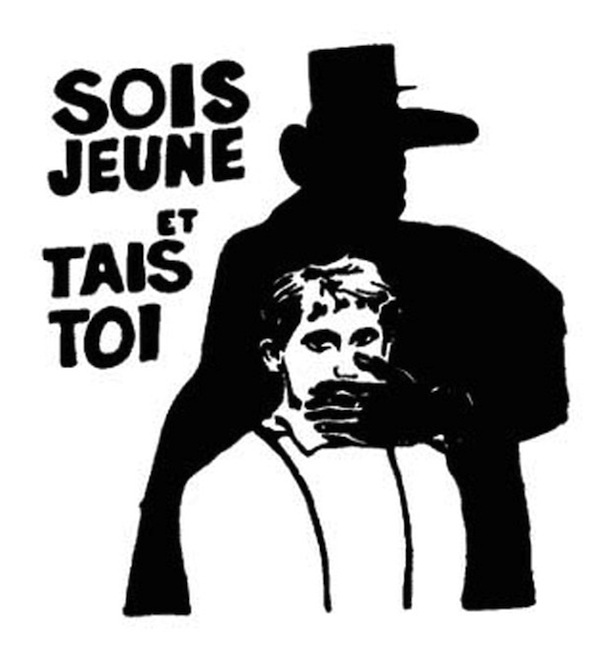

‘Sois Jeune et Tais Toi’ – Be Young and Shut Up, May 1968. Image from Qwiki.

It is always intriguing to revisit the ideas of Paul Goodman; not exclusively for his writing on sexuality, film and politics, but also for his pertinacious desire to problematise key aspects of American society during the 1950s and 1960s. Goodman’s ideas on education were provocative and challenged ‘organised’ society by contesting what appeared to him as the distorted constitution of social order. The cant of anarchism is impractical and an idyllic fantasy, but some of Goodman’s ideas are highly persuasive. It would be appropriate to begin what is hopefully a laconic critique of the government’s leadership programme with a quote from an essay Goodman wrote to the New York Review of Books in 1969 titled, The Present Moment in Education; ‘there is an authentic demand for Young People’s Power, their right to take part in initiating and deciding the functions of society that concern them – as well, of course, as governing their own lives, which are nobody else’s business…the young have the right to power because they are directly affected by what goes on…their point of view is indispensable to cope with changing conditions, they themselves being part of the changing conditions.’ This seems improbable when we have to contend and grapple with that abject, conservative and premodern condition: the instructive and authoritative right of the elderly over innocuous, pliable and apparently unlettered ‘youth,’ who require tyrannical guidance against the malevolence of the world. The political extension of this idea of submission and servility to absolute authority now has its principal specimen in a ‘mandatory’ youth leadership programme and it is the enormity of the latter that we must draw and quarter.

The idea that this form of indoctrination should be forced upon university students, and its acceptance by many in the country, is a remarkable detraction from what we strive to establish – a progressive and pluralistic society. It not only warrants opposition by university students, but also by the citizenry of this country if there is to be a genuine attempt at reclaiming our civil liberties from a government that is increasingly inclined towards manufacturing subservience. The attempt to locate an ‘authentic demand’ for student power in Sri Lanka is onerous, but the potential for the development of a widespread student movement that moves on the issues of indoctrination and the militarisation of education presents a compelling vehicle of political power and dissent. There is, however, a fundamental flaw with the expression and organisation of student power and politics: it can be completely spontaneous, emotive, unsophisticated and potentially violent, but yet it is almost consistently ephemeral due to the exposure to a culture of fear and impunity and a violent intolerance of dissent. This is perhaps further aided, to a certain extent, by the quiet acquiescence to authoritarian politics, which has hindered the emergence of a robustly politicised intellectual class. While student unions such as the Inter-University Students Federation (IUSF) deliver meek statements condemning the leadership programme, I have not witnessed any urgency for the adoption of a more confrontational paradigm of opposition, and it is quite obvious that the involvement of the Defence Ministry and the military has resulted in widespread circumspection. This is perhaps due to the social nexus between that of the army and a majority of citizens; for three decades, the army has been considered as an enforcer and noble guardian, which was conditioned by the jingoistic nature of verbalisation during the war by political leaders and state media. While for the minority that was directly affected by the war and others, this relationship – to put it politely – is ‘problematic.’ However, the blurring of lines in this context is quite clear: the increasingly visible post-war militarisation of society was preceded by the socialisation of the military during the war. How then could we expect widespread opposition to the ‘noble’ role of the army in this programme? After all, ‘leaders are not born, the army makes them.’ I wonder, how did the most celebrated leader in Sri Lanka manage with the inadequacy of not being ‘produced’ by the army?

It is, therefore, comprehensible why most of us will struggle to locate a more pronounced language of protest against a programme of indoctrination that aspires to inculcate military values and encourage the sort of discipline that – if allowed to germinate – results in the production of ‘global graduates.‘ I see no qualitative connexion between training programmes of such little substance and the emergence of accomplished graduates. As a result, the legitimisation of more clamourous opposition by student unions, the respective chancellors and vice-chancellors of universities, civil society and university students is found desperately wanting – if not desirable and necessary – in order to contest what appears to be the unqualified attempt by this government to restrict ‘student politics,’ produce a cult of conformity and impose a uniformity with respect to the comportment of university students. While we should concern ourselves in equal measure with the problem of academic freedom in the country, it is necessary to oppose any possible move to restrict the freedom of expression, freedom of association and right to assembly in public universities. I do not feel the need to deal with the content of the programme because it comprises of such astounding idiocy and profligacy, and I believe that the Young Researchers’ Collective has dealt with that aspect adequately. The issues then that force my pen are: the necessity and reasoning of the leadership programme, the deception that led to the false condition of mandatory participation and the contemptible opposition to the programme that we have witnessed thus far.

A few lines are required, firstly, for a tepid exposé on what I believe is the deceit of the Ministry of Higher Education, and secondly, for a brief exegesis on the raison d’état of the leadership programme. There is a certain degree of confusion apropos to whether participation in the leadership programme is mandatory and essential for entrance into university. The Secretary to the Ministry of Higher Education, Dr. Sunil Navaratne, was kind enough to inform the public last week that the programme was ‘not compulsory contrary to popular belief.’ One would expect Dr. Navaratne to be aware of what occurs at the ministry, particularly when the Minister for Higher Education, S.B Dissanayake, appears to have been the source of this ‘popular belief.’ If this is the standard of policy-making, comprehension and administration that prevails within the Ministry of Higher Education, an institution responsible for improving the quality of tertiary education, then it appears that the allocation of the portfolio to that parvenu S.B Dissanayake was not undertaken in complete consideration of the public interest. It is possible that incorrect reportage and miscommunication resulted in this inexcusable error, but then how would Dr. Navaratne and Minister Dissanayake explain the fact that the letters dispatched in Sinhala, Tamil and English by the Ministry emphasise mandatory participation? The second and tenth paragraph of the letter informs the students that the ‘certificate,’ which confirms the completion of the programme, is ‘required for entry to the university’ and the Tamil letter further states that participation in the programme is ‘an essential and mandatory precondition for entrance into university.’ Since the Ministry of Defence was so expeditious to provide an example of ‘public accountability’ last week, it is certainly desirable – on the charge of deceiving the public – for Minister Dissanayake and Dr. Navaratne to tender their letters of resignation immediately.

The political motivations of the leadership programme are quite clear when we consider that it is essentially a retributive reaction to the student protests that occurred in October and November 2010. It also provides an opportunity for the government to restrict the political influence of opposition parties within the university system and student politics, which presents a potential force of mobilisation against the government. A brief recapitulation of the student protests will remind us that they were as much about critical issues confronting the system of higher education in this country – unemployment, reform, privatisation and the provision of adequate facilities for students – as they were about the government’s whimpering about the political influence of the JVP. As a result the collective action that we witnessed during that period apparently occurred for the right reasons, particularly as it was in opposition to proposals put forward by the government that the protestors considered to be inimical to their interests. I do support the establishment of private universities, but at the same time wider educational reform policies – with increased funding and better facilities that allow for expansion – are required for public universities to maintain a competitive edge. In consideration of the importance of reform, it is worth posing these questions: (i) What is the status of President Rajapakse’s commitment to a higher education development initiative that is worth Rs. 3,000 million? (ii) What has happened to the plan for the further investment of Rs. 600 million to transform the Peradeniya, Moratuwa, Colombo, Sri Jayawardenapura, Kelaniya and Ruhuna universities? (iii) How much funding is allocated for the provision and/or redevelopment of comparable facilities and equipment?

I have not read a convincing justification for the stamping out of student politics and if one exists, which I am sure it does not, it is antithetical to the fundamental principles of a liberal democracy. The attempt, by the government, at political or apolitical massification, to wit an action of organised ‘homogenisation,’ is surreptitious. I consider political groupings within the student body and the articulation of their socio-political interests as a positive indicator of civic engagement. As such, the emphasis on ‘physical and mental discipline’ is problematic when individuals are ‘forced’ to participate and one should take particular offence that President Rajapaksa considers it necessary for instruction to be provided on ‘positive attitudes and love for the country‘ in order militate against student protests in public universities. This is an unfortunate view of how citizens are expected to conform to the excesses of this government, and it also appears that there is a gross misunderstanding with respect to the difference between ‘loving’ your country and demonstrating utter contempt and disregard for the policies and actions of your government. An editorial in the Daily News falters in a similar manner with this erroneous reasoning: “…students’ unions…in league with political forces which are hostile towards the state.” I believe that the student protests last year were against the government – the bureaucracy that manages and exercises power through the state apparatus, deliberates on key concerns of citizens and develops policies – and not the state as a sovereign political institution.

The other issue that has received much attention is the problem of ‘ragging,’ which has developed into an institutionalised practise within a majority of universities. Perhaps a greater tragedy is the complicity of lecturers and other university officials who in complete indifference accept ragging as a ‘rite of passage’ within a hierarchical system of senior dominance over freshers/juniors. It is sufficiently amusing – in consideration of the egalitarian pretence of boot camp society – that the instruction of an alternative hierarchical system with a similar call for subordination is the solution to ragging. Is it exceedingly ambitious to request the chancellors and senior lecturers of universities to set about establishing intelligent administration in order address the issue by expelling students who are guilty of physical abuse? I do not consider any other measure – especially one that is not punitive – to be effective and I would go so as far as to argue that ragging should be criminalised. The suspected fons et origo of this controversy is the JVP and much has been written over the last few weeks about the need to mitigate its influence in public universities in order to prevent ragging, protests and violence. The idea that one political party is the cause for an inherent practise is ridiculous and I have to reiterate that systematic action, such as the ban on ragging by the Supreme Court of India, is a possible course of action that needs to be replicated.

The fundamental connexion between academic freedom, critical thinking and the freedom of speech allows for the development of an intellectual society that is provided with the liberty to oppose the status quo: as such, the notions of contrarianism, non-violent or violent opposition to tyranny, participation in political activism, deliberation and individual expression are key components of positive citizenship. I am reminded of two significant student protests that utilised the latter principles for a wider movement of opposition and reform: the Free Speech Movement – a series of protests at the University of California, Berkeley that occurred between 1964 and 1965 against the proscription of political activities on campus and for the freedom of speech – led to the withdrawal of restrictions by the administration. The mass student protest on the 10th of May 1968 in Paris in reaction to traditional society, authoritarianism and capitalism, which almost led to the collapse of De Gaulle’s government after millions of workers joined the protest, was the apogee of student power during the 1960s. It is possible that in Sri Lanka the student body as a ‘centre’ of dissent, particularly when we consider the potential for mobilisation in public universities, could develop a substantive reform and oppositional movement. I find the mobilisation of a mass young intellectual class relevant in a context where the power of opposition political parties to act as a check and balance on the government is insignificant – as Mill stated in his essay On Liberty, “the most cogent reason for restricting the interference of government, is the great evil of adding unnecessarily to its power.” I have to applaud the Young Researchers’ Collective for taking a stand on the programme, and I wait, perhaps in vain, for an organisation like ‘Sri Lanka Unites,’ which claims to focus on leadership, reconciliation, justice and youth empowerment, to issue a statement. I would hope that responsibility is not a burden, but instead a call to action. Even if a mass student movement fails to pressurise the government to consider a wider educational reform project, the degree of organisation and politicisation could result in the emergence of multiple reform-oriented ‘pressure groups,’ which may fill the void left by a disengaged intelligentsia for the sole purpose of addressing the direction of post-war policy-making and sustaining dissent.