[Editors note: For an in-depth interview on Sri Lanka’s human-elephant conflict, see Humans vs. elephants: Sri Lanka’s tragic on-going conflict]

If those hardy Englishmen and Scotsmen who ran large tea plantations in Ceylon were far removed from the local people and realities, western movie makers were much more so. They could just as well have come from another planet to catch glimpses of an exotic island.

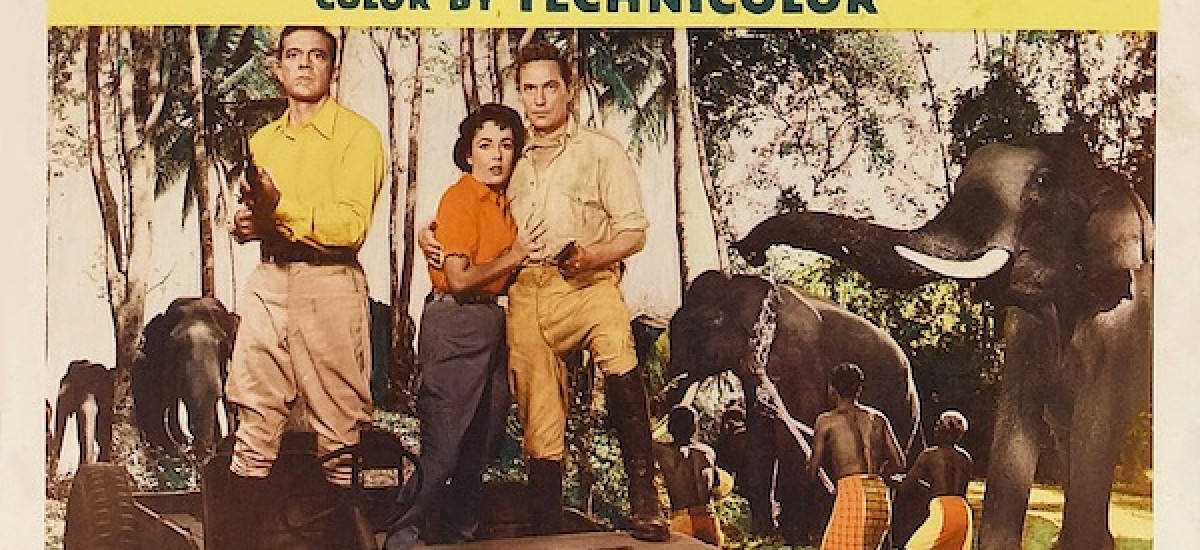

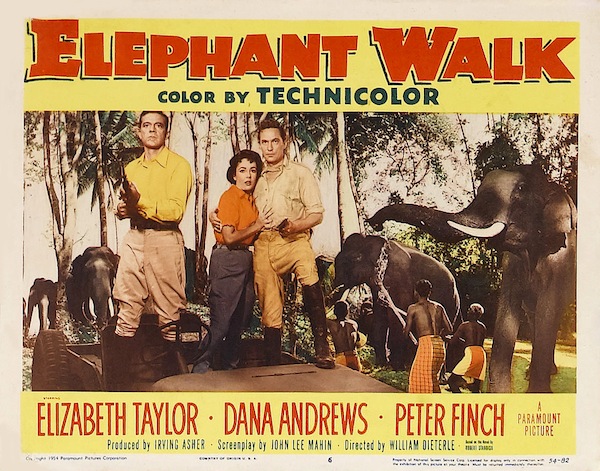

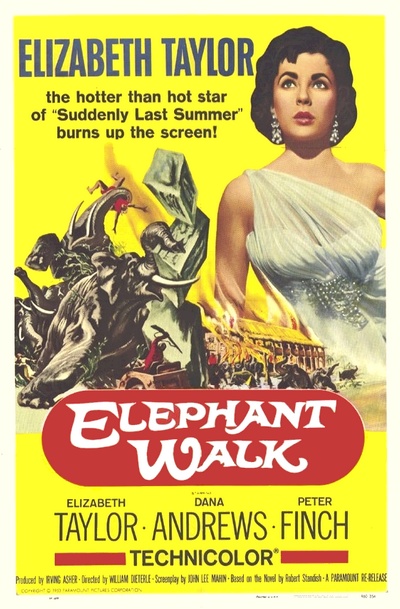

But feature film makers everywhere enjoy the artistic license to create whole new worlds, and we willingly suspend our disbelief when watching their creations. Elephant Walk (103 mins, colour), released by Paramount Pictures in April 1954, may not be the most artistic or technically perfect movie from that era. Yet, more than half a century after it was shot on location in Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), the film can still hold an audience captivated with a sense of drama and intrigue.

Elephant Walk was directed by William Dieterle, and based on the 1948 novel with the same title, written by “Robert Standish” — actually the pseudonym of English novelist Digby George Gerahty (1898-1981). It starred Elizabeth Taylor, Dana Andrews, Peter Finch and Abraham Sofaer.

This film was among several that were shot on location in Ceylon in the 1950s when Hollywood studios ‘discovered’ the island as an exotic, relatively inexpensive and hassle-free location. But this is the only one whose story is actually set in Ceylon.

Much of the movie’s historical appeal stems from the involvement of Elizabeth Taylor. She plays the character of Ruth, a young woman who marries a British tea planter, John Wiley, and follows him to Ceylon. She soon finds out that things aren’t entirely idyllic in the tropical paradise.

The husband’s late father had built the estate bungalow on the path where elephants routinely migrate. With their long memories and entrenched habits, they have resented that misappropriation ever since. The occasional confrontations between estate workers and elephants culminate when the pachyderms charge en masse just when the estate’s population is weakened and distracted by a cholera epidemic…

Vivien Leigh, one of Hollywood’s biggest stars at the time, was originally cast to play Ruth Wiley’s role. She even arrived in Ceylon and filmed some scenes before she developed bipolar disorder. So Liz Taylor, at 22 already well on her way to the A-List, was hurriedly called in. (Many long shots — and some from behind — used in the final edit are actually those of Leigh!)

Prescient movie?

However, Elephant Walk’s significance does not rely solely on Liz Taylor’s alluring screen presence or Vivien Leigh’s derrière. The movie has been remarkably prescient on several fronts, which can only be appreciated now — in another century, and on a wholly different island. A key theme of the movie was the human-elephant conflict, but passing references to social exclusion and rampant poverty in post-independent Ceylon are also of much interest.

I doubt if Paramount’s writers were intentionally making any social commentary. One of the studio’s co-founders, Samuel Goldwyn, had famously cautioned against it. When asked about movies with a “message” some years earlier, he had replied, “If you want to send a message, use Western Union.”

Nevertheless, the movie (and perhaps the book on which it is based, which I haven’t read) was contrasting the British planters’ opulent lifestyle with the forced austerity in post-War Britain. Even more striking is the poverty and squalor among the hundreds of resident workers whose sweat, toil — and occasional tears — ensured that the ‘cups that cheer’ were always brimming.

Perhaps it wasn’t so evident at the time the movie was first released, but it is also a celluloid requiem to the British Empire on which the sun was decidedly setting, and the Plantation Raj whose halcyon days were receding into the past. The hard-working and hard-drinking white males, taming the hilly terrain in the humid tropics, would be the last of their kind.

‘Brown Sahibs’ had already taken over the reins of political power in Colombo. Up in the salubrious hills, where life moved at a slower pace, the winds of change had just begun to gain momentum. In less than half a generation, it would become a gale of nationalisation dismantling one of the most efficient inter-continental industrial operations launched during the Victorian era.

The 1970s were particularly turbulent for the island’s plantation sector. The remaining British plantation companies were unceremoniously ushered out. Well-intended but badly implemented land reforms brought down the quality, productivity and global competitiveness of Ceylon Tea. Although these socialist misadventures were mercifully short-lived, they inflicted enough damage: even after three decades of economic liberalisation, the industry has yet to recover completely.

Despite all the socialist rhetoric that justified it, nationalisation didn’t deliver that many social benefits either. A case in point: Sri Lanka’s one million strong plantation workers still have markedly lower social indicators. In fact, the poor housing and sanitary conditions that triggered an outbreak of cholera in Elephant Walk still persist on some tea estates. There is still an enormous gulf in the quality of living (and lifestyles) of plantation managers and their resident workers — except that the masters are no longer white.

In the mid 1990s, while researching a series of articles on the socio-economic status of plantation communities, I came face to face with this stark reality. The workers, descendents of indentured labourers that the British brought in from southern India, remain trapped in the past. Their deprivation is often masked by the country’s impressive national level human development indicators.

DDT Generation

But back in the early 1950s, when the movie’s story takes place, the party was still in full swing — albeit under the bemused eyes of the locals and the piercing gaze of the elephants.

In 1953, the year Elephant Walk was filmed, Ceylon was experiencing a post-War and post-independence population boom, aided and abetted by DDT that had drastically reduced deaths from malaria. A census that year revealed a little over 8 million people. This number has swelled more than two and half times since: exactly how many of us walk this island will be known by end 2011, when our first full head count in 30 years is completed.

By coincidence, the first ever scientific census of wild elephants in Sri Lanka is also taking place this year. It should reveal just how much our growing numbers — and rising consumption patterns — have impacted the largest mammals who share this crowded island.

Elephant Walk ends with the dispossessed herd reclaiming its lost migratory route. The luxurious bungalow burns down in the climaxing rampage. (To the discerning eye, the elephants look too tame, and the ‘rampage’ too orderly. That is understandable: even the most dare-devil Hollywood stunt director can’t get wild elephants to follow a script. So, according to the Internet Movie Database, circus elephants were used.)

As the humans escape with their lives, John Wiley looks at his house on fire with equanimity. He promises Ruth to build a new place “somewhere else.” Let the elephants have this patch.

If only life imitated art in this respect, the story of the Lankan elephant might have been different. But the determination and ruthlessness with which large scale irrigation and agricultural development projects were pursued since the 1950s left no room for such sentimentality.

Tracing the roots of Sri Lanka’s human-elephant conflict, conservationist Jayantha Jayewardene wrote in 1994: “Where their normal migratory routes were impeded by development, the elephants came into confrontation with the new settlers who had displaced them from their habitats. Here they found a ready source of food in the new crops that had been cultivated. The human-elephant confrontations and subsequently conflicts began. With the increasing pressure for sufficient food in the forests, the elephants not only moved into the new settlements but were practically forced to move into the old (purana) villages as well. The elephants had hitherto co-existed peacefully with the purana villages but here too, conflicts began to surface.” (The Elephant in Sri Lanka, p96).

How best to resolve this long-simmering conflict is still being debated by scientists, environmentalists and officials. Meanwhile, every passing year, a few dozen elephants and humans are killed in increasingly violent encounters, further diminishing the prospects of a peaceful co-existence.

Finally, Elephant Walk to me is yet another visual reminder of just how dependent we are on the seasonal Indian Oceanic winds called the Monsoons that bring us most of our rain. Everyone — from the mighty tuskers and arrogant planters to the humblest subsistence farmers — hopes and yearns for a timely and ample Monsoon. (As I write this, in late May, 20 million Lankans are anxiously awaiting the arrival of the more potent South-west Monsoon.)

We are not alone. Close to two billion other Asians share our climatic legacy and predicament. Faced with accelerated climate change, we should worry far more about likely disruptions to these life-giving, rain-bearing winds. Scientists have recently warned that delayed and/or weakened Monsoons could hit us sooner — and harder — than the widely feared rise in sea levels.

Like it or not, we are all Children of the Monsoon.

PS: The mix of Empire, Plantation Raj and the Monsoon continues to attract film makers. An enchanting treatment of these elements, somewhat reminiscent of Elephant Walk but with a clear political element, is found in Before the Rains (98 mins, 2007). This Indian-British production, directed (and beautifully shot) by Santosh Sivan and featuring Nandita Das in a lead role, is set in Kerala’s Malabar District in the 1930s. The story — with much stronger characters and ‘native’ sentiments — unfolds against the backdrop of a growing Indian nationalist movement.

Science writer Nalaka Gunawardene is far more interested in human-induced wild-life than wildlife in the jungles. He blogs on science, development and conservation issues at https://movingimages.wordpress.com He thanks Richard Boyle for his inputs to this essay.