A number of columnists have commented on the various different aspects of the Provincial Council elections held in 2008 /2009 beginning with the Eastern PC elections in May 2008. These comments have ranged from increasing election fatigue, the costs to the tax payer, the phenomenon of the new contenders, and implications of results for future parliamentary and presidential elections. Here I would like to focus on the nominations given to women and women’s representation in PCs following these elections.

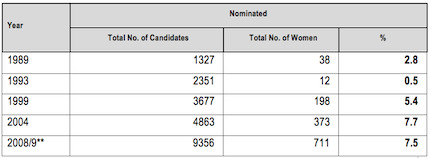

According to statistics from the Department of Elections a total of 31 political parties and numerous Independent groups (as many as 13 in some districts) contested for the 417 seats in the 8 PC elections held between May 2008 and October 2008. A staggering 9356 candidates were given nominations, almost double the number at the 2004 PC elections. 711 women were among the candidates i.e 7.5% of the total number of candidates. As Table No. 1 indicates this is slightly less than the number of nominations received by women at the 2004 elections. This reduction was however mainly due to the very low number of nominations given to women at the Eastern provincial council elections which brought down the overall % of women candidates at these elections.

Table 1: Nominations at provincial council elections and numbers of women elected 1989 – 2008/2009

Source: Department of Census and Statistics (2007), Leiten (2000), De Silva (1995: 233). 2008/2009 nomination statistics were personally compiled with assistance from Department of Elections officials.

* Statistics were not available at the time of completing this study.

** 2008/2009 statistics are only for six provincial council elections held in 2008 and up to June 2009.

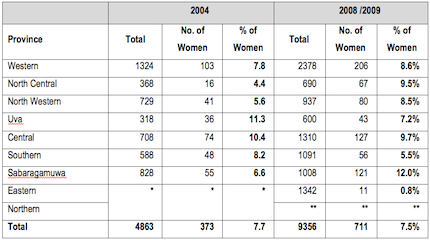

Table 2: No. of candidates at Provincial Council elections held in 2004 and 2008/2009

Source: Department of Census and Statistics (2007). 2008/2009 statistics were personally compiled with assistance from Department of Elections officials.

* Elections not held

** Elections to be held.

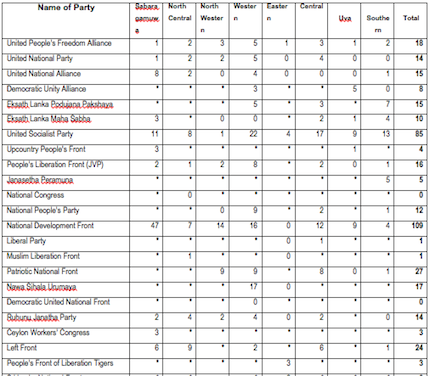

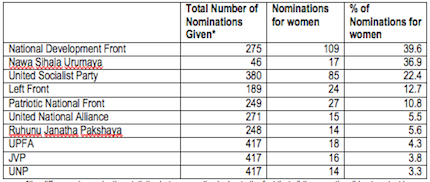

Some provinces did record a dramatic increase in nominations for women. For instance in the North Central Province, nominations rose from 4.4% in 2004 to 9.5% in 2008 and in Sabaragamuwa from 6.6% to 12.0%. This increase is primarily due to a few small parties and independent groups giving a bulk of their nominations to women The National Development Front was responsible for the highest percentage of nominations for women (39.6%) followed by the Nawa Sihala Urumaya (36.9%) and United Socialist Party (22.4%). The motivations of these parties in giving nominations to women, the agency and experience of women in this process as well as voter perceptions if any on the fact of more women contesting from these parties is worthy of further study. Unfortunately none of these parties win seats at the national, provincial or local level and therefore nominations by them do not translate into seats for women.

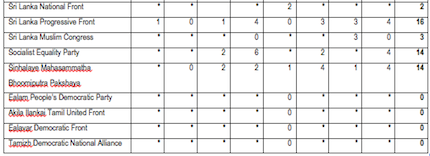

In contrast, the two major parties/alliances, the UPFA and the UNP which won the bulk of seats at the elections continued to by and large disregard women candidates. The total number of nominations given to women by the UPFA and UNP amounted to only 4.3% and 3.3% of nominations (See Tables 3 and 4). The statistics suggest that even parties who traditionally had a better record of nominating women when contesting on their own such as the Lanka Sama Samaja Party (LSSP) and the Communist Party (CP) maybe retreating on nominations for women under coalition politics of the UPFA.

Table 3: Provincial Council Elections 2008/ 2009 − Party-wise breakdown of nominations for women

![]()

Source: Statistics personally compiled with assistance from officials at the Department of Elections.

* Did not contest these elections.

Table 4: Selected Party wise Nominations for women in Provincial Council elections 2008/ first half of 2009

* the difference in nomination statistics between parties is due to the fact that all these parties did not contest in every District.

This is notwithstanding their elections manifestos which make explicit commitments to increase nominations for women. Mahinda Chinthanaya as we all know states,

I will arrange to increases (sic) the number of nominations of women to a minimum of 25% of the total number of candidates in respect of Provincial Councils and Local Government (Article 14 of the Manifesto).

Ranil Wickramasinghe’s People’s Agenda made a similar promise under the section ‘Empowerment of Women’ stating that he will take action to systematically remove all social and economic obstacles which hinder the implementation of the Women’s Charter which explicitly commits to increasing nominations for women (Art. 2 (i) b) while also ensuring 30% minimum representation of women in the central decision making committees of all political parties within three years of coming to power.

In fact it is extremely disappointing that the UNP which played a pioneering role in recognising the need to increase women’s representation in its Women’s Manifesto of 2000 now seems to be trailing the UPFA on this issue.

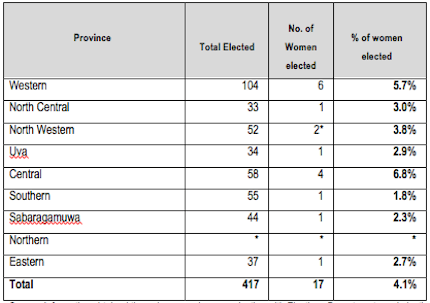

Representation in Provincial Councils

Following these elections women’s representation in provincial councils now stand at 4.1% (see table 5). 0.9% point lower than in 2004.

Table 5: Provincial Council elections 2008/2009 – Nominations for women and number of women elected

Source: Information obtained through personal communication with Elections Department, and elections reports of People’s Actions for Free and Fair Elections (PAFFREL). Not official statistics.

* Elections to be held.

** Three women were elected when elections were held, however Soma Kumari Tennekoon passed away in September 2009 and was replaced by a male candidate.

Despite the UPFA and UNP record in relation to nominations for women, all of the women currently elected to provincial councils are from the UPFA and the UNP. In fact of the 32 women who received nominations from the UPFA and UNP, 18 of them won their seats. That is more than 50% of the women candidates. Some won resoundingly.

The elected women councillors include both old hands with long histories of working within their parties as well as completely new contenders with no prior experience in politics. Some are predictably from political families, while others are politicians in their own right with no family connections to politics. A majority of women elected were incumbent provincial councillors who managed to hold on to their seats. There were also a few who were able to move ‘up’ from local level elected bodies – no easy task within the political culture in SL.

The fact that these Councillors come from such diverse backgrounds means that the phenomenon of widows, wives and daughters may no longer be the most dominant trend in the case of women coming into politics. In fact these elected women’s pathways to politics don’t follow any discernible pattern or trend. While nominations to candidates such as Anarkali cannot be supported in principle because they are made overlooking other loyal party women who have worked for the party for years at the district/provincial level, these elections demonstrate that with the right kind of support from their parties, women from widely differing backgrounds can hold their own in electoral politics.