Featured image by Amalini De Sayrah

In March 2018, mob violence visited pockets in an East to West arc from 5-20 kilometres North of Kandy. The state is obligated to ensure the safety of its citizens and it failed to do so. In spite of urgent warnings of impending violence and reassurances by senior officials, the Police were bystanders at critical junctures. Now, at a minimum, the state is obligated to restore the property, health and well-being of the affected expeditiously. After 100 days, there is cause for alarm.

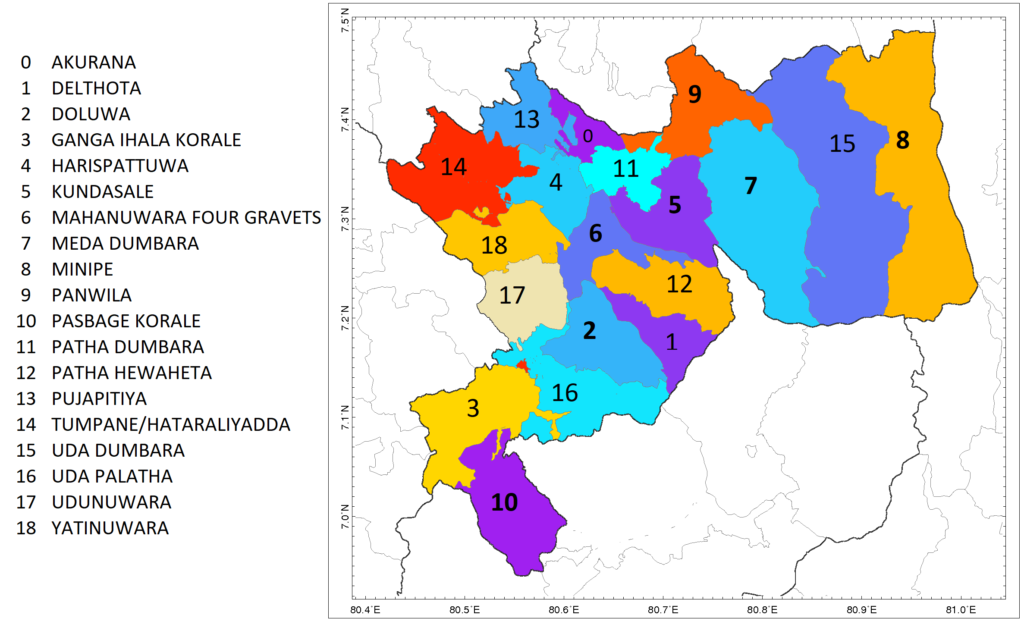

Map 1: The 20 Divisional Secretariats in Kandy are shown – with Hathariyadda and Tumpane combined. Violence started in Medadumbara (7), spread to Kundasale (5), and in the following day to Patha Dumbara, and on the 4th day to to Pujapitiya, Harispattuwa, Akurana, and Yatinuwara.

Soon after the violence, the victims were assured by the Prime Minister, visiting Ministers, the Army commander, and officials of full and quick restitution. The Prime Minister urged that the rehabilitation be completed in 4 months. The Army commander assured that the buildings will be rebuilt by the Army as the President will release funds for this. However, after the initial debris clearance, the army has withdrawn, and there has been little restitution by the state.

In mid-March, an initial compensation amount was paid – approximately Rs. 100,000 for a destroyed business and Rs. 50,000 for a destroyed house. In all, about Rs. 10 million has been disbursed to the worst affected. For them, these amounts are only helpful for getting through the days while displaced, for cleaning debris, or for going from office to office in search of redress.

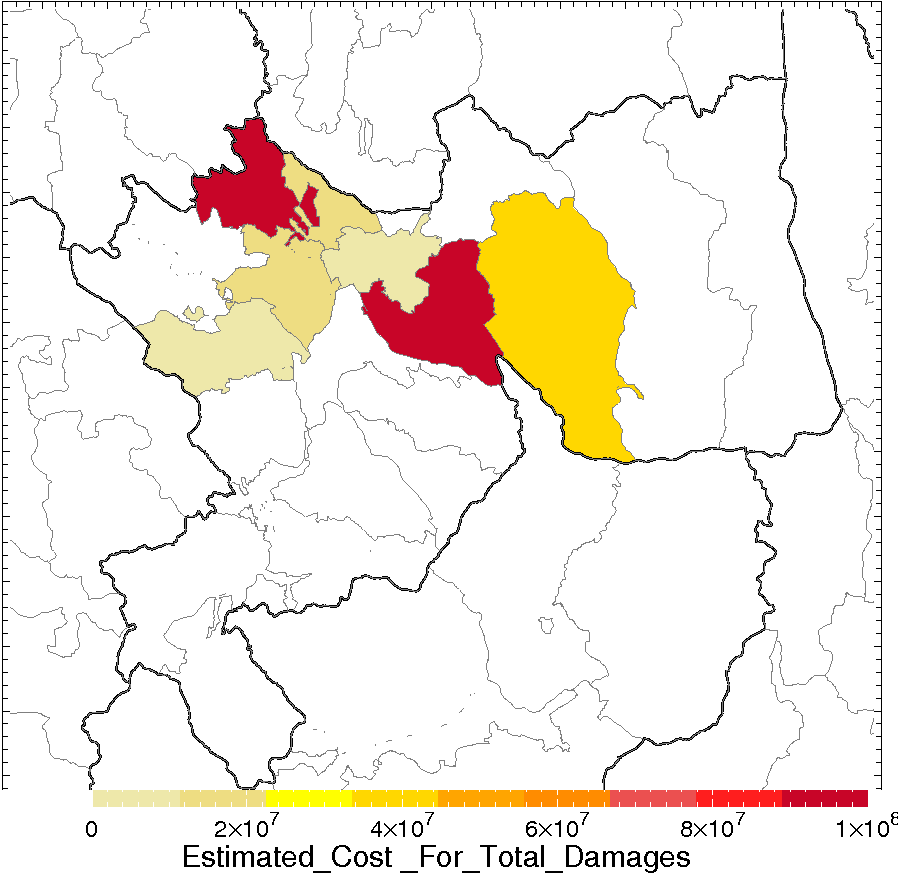

Map 2: Loss Assessments in Rupees for Businesses, Residences and Religious Places put together by civil society. Largest losses were in Kundasale, followed by Pujapitiya, Akurana, Harispattuwa, Yatinuwara and Patha Dumbara.

Since early March, officials have been assessing losses and have made victims understand that their assessment shall form the basis of rehabilitation and restoration by the state. Below, we describe the available assessments and compare it with that undertaken by civil society.

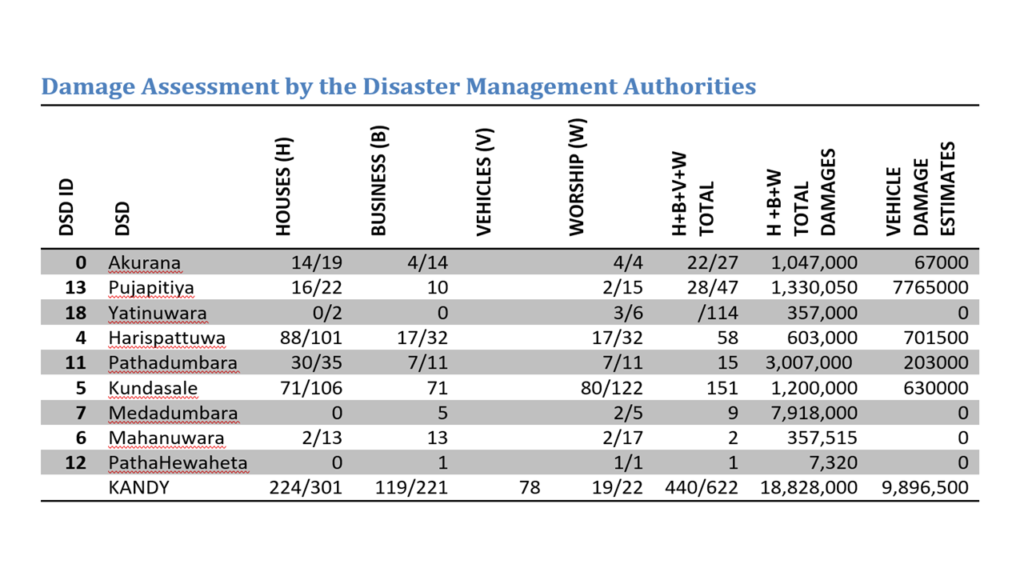

Damage Assessments by the State

At the local level, each of the affected Divisional Secretariats (DS) (Map 1) were tasked with estimating the damages. These DS officers have visited the affected sites and summoned the affected multiple times and identified 622 victims due restitution. By May 1st they were able to assess properties of about 440 of those affected including 224 houses of 301, 119 businesses of 221, of 78 vehicles and 19 of 22 religious places. These assessments were stymied in several cases as the displaced do not have all the documentary evidence that the officials feel they need to accept a claim. Since then the officials state that they have not completed fully completed the assessments and therefore do not want to release any information.

The DS division with the largest number of damaged buildings and vehicles were Kundasale, Yatinuwara and Pujapitiya. The DS division with the largest loss estimates were Kundasale, Akurana, Pujapitiya and Medamahanuwara.

Table 1: Loss estimates compiled by the Kandy District Disaster Management Authorities. The fraction shows the assessed cases/ total cases.

Table 1: Loss estimates compiled by the Kandy District Disaster Management Authorities. The fraction shows the assessed cases/ total cases.

These tabulations at the Divisional Secretariat level were compiled by the District Disaster Management officials and forwarded it to the Ministry of Relief and Rehabilitation. In the case of the up to 21 mosques and 1 temple they communicated the assessment to the Ministries of Muslim Religious Affairs and Buddha Sasana respectively.

By May 1, their aggregate estimate of loss for these 440 cases was Rs. 28 million. Anyone who has seen photographs of the damage and has any idea of construction costs locally will know that such an aggregate is ridiculous. This value may go up as some of the more difficult assessments are pending. However, the estimates so far are far too low.

After the initial release of information on May 1, state officials have been unwilling to release updates even at aggregate scales. In addition, even many of the victims are not provided with the state’s estimate of their own losses. The victims are not in a position to complain as they need the blessings of these local officials for managing basic functions.

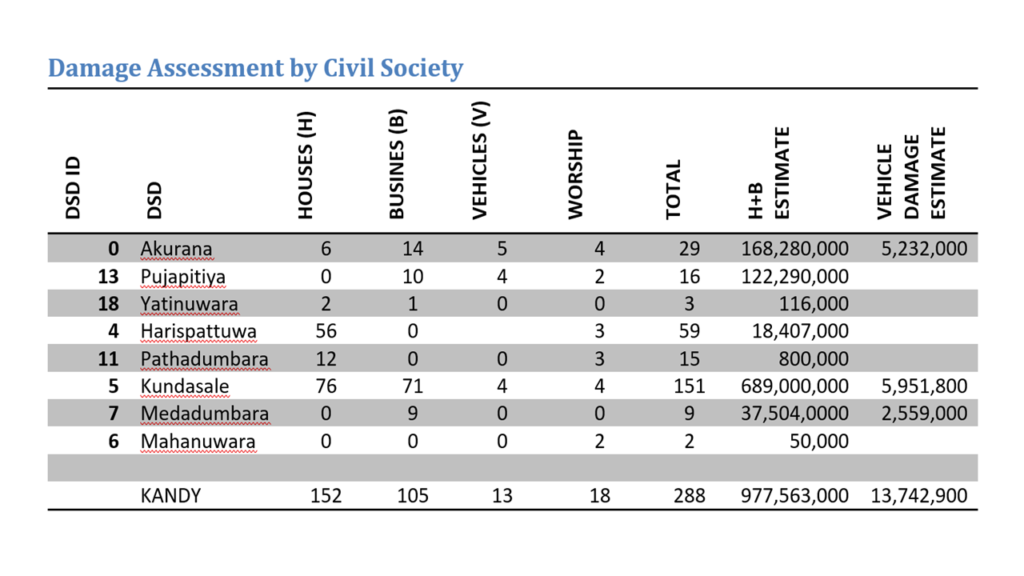

Damage Assessments by Civil Society

There has been a community effort to put together assessments of damages so as to facilitate disbursing private donations to take care of the most urgent needs until the state delivers. The assessments were done by volunteers and civil society groups. They compiled the estimates through interviews, site visits, expert inputs and peer review. As there is a common pool of limited funds to be disbursed there are checks and balances to the process. The total estimate that this effort has come up with for 292 cases is a billion rupees.

Table 2: Loss estimates compiled by civil society. Note 292 cases were compiled compared with 440 of the state. Although half as many cases were assessed by the Civil Society, their estimate of damages is much higher.

Table 2: Loss estimates compiled by civil society. Note 292 cases were compiled compared with 440 of the state. Although half as many cases were assessed by the Civil Society, their estimate of damages is much higher.

Lessons and Next Steps

Assurances were given that reconstruction would be completed within 4 months. With two weeks to go, even the assessments have not been completed. The causes of delay – delays in processing at particular offices, lack of skill or procedures and policies that unduly delay – should be documented and understood so that they can be mitigated in future.

Given the lack of transparency, the best we can make out is that the state apparatus has under-estimated the losses by around 10-50 fold.

These gross under-estimates will lead to profound losses for the affected with long-term impacts of alienation and bitterness, a perceived lack of deterrent action against future mob violence on the part of the State and the mob leaders feeling they have accomplished their goals to encourage similar future enterprise.

The reasons for delays and under-estimates have to be documented, understood and rectified particularly as

- officials have not been transparent – concealing information or erecting barriers to avoid criticism is unacceptable.

- The reasons adduced for under assessment – such as low assessments for taxes or insurance needs to be countered. The abiding principle has to be the restoration of the property of the victims.

- Some assessments are delayed or lowered because many have lost ID cards, deeds and other records from violence. As done by civil society, other methods have to be found. In any case, the state owes these victims much more than just compensation for documentable property damage.

- Empathetic officials who are fluent in Tamil have to be brought in particularly to help most female victims.

- Many of the affected need assistance with dealing with officials and support through psycho-social counseling.

- There should be an Ombudsman to advocate for the victims.

The citizenry, civil society and the media should push for

- transparency

- quick rectifications of inadequate assessments or alternative the state should take over reconstruction and replacement of properties

- expediting the reconstruction and

- to publicise the obvious shortcomings in processes.

Given the Army’s demonstrated ability in the aftermath of violence in Aluthgama to bulldoze red-tape, and get around the shortcomings of officialdom including in assessments, the Commanders initial willingness to rebuild if tasked should be taken up.

The larger lessons, and long-term social impacts have to be documented. The promised Presidential Commission of three retired judges is essential. The National Police Commission must release reports from itself and the Police. The Human Rights Commission should publicly release its report and follow up. In addition, a fuller accounting of the societal, commercial, livelihood and national damage is needed.

If these steps are not taken then the State shall not acknowledge the costs passed on to the victims and endured more generally. Nor is there a platform to promote accountability, to identify bottlenecks, reforms of institutions and policies, recognition of the grave underlying problems, and the enabling of a healthier engagement between the citizen and the State. Absent such reform, mob violence shall recur as entrepreneurship in extremism that leads to violence has a viable business model in Sri Lanka.

Editor’s Note: Also read, “Kandy: The damage and the distrust” and “Untold Stories from Kandy“

The authors can be contacted via disasterservicescentre@gmail.