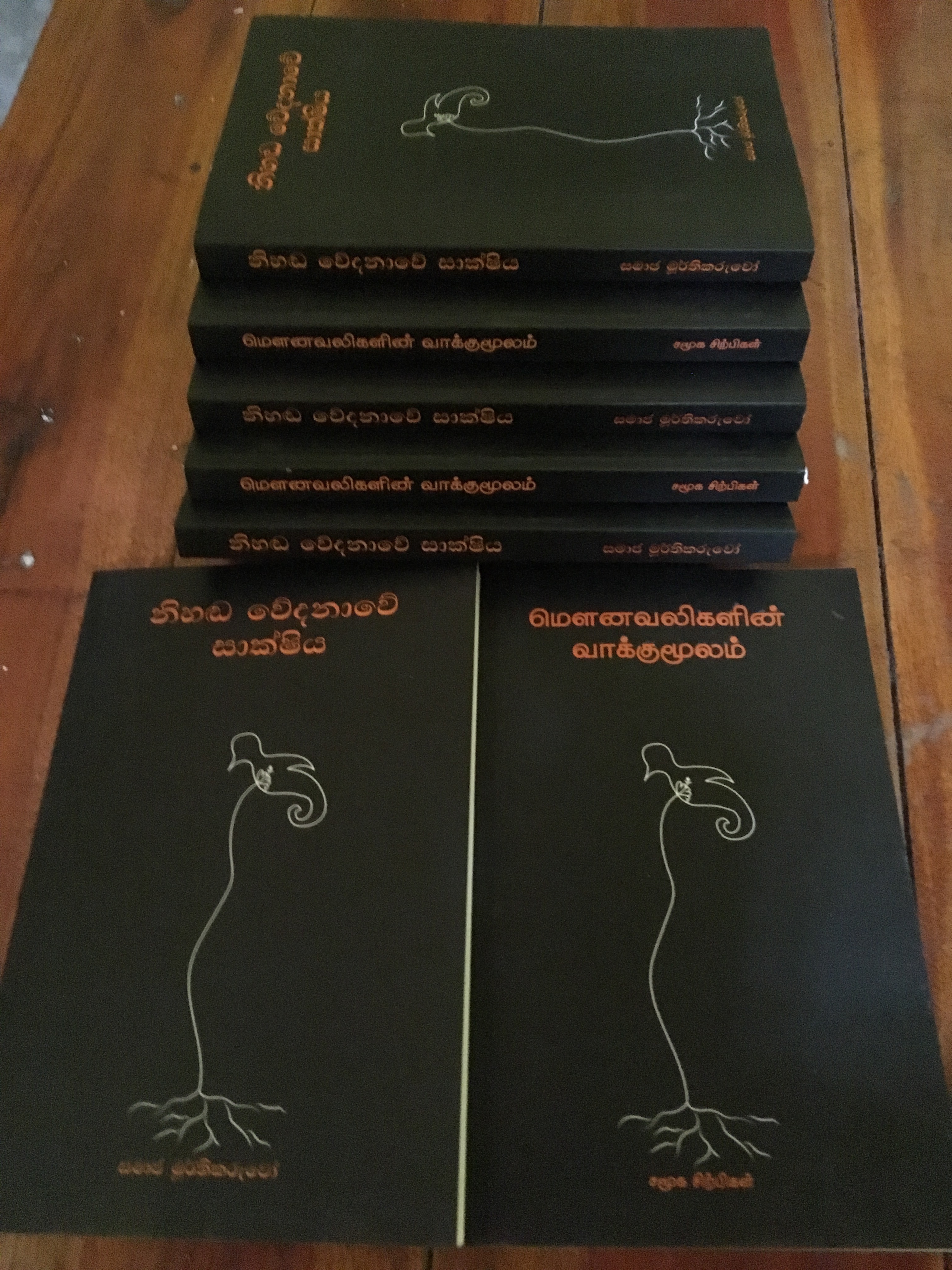

It gives me great pleasure to join you – young women and men writers – as you launch your work in the anthology ‘Testimonies of Silent Pain’.

I will be speaking in English. As Professor in the Department of English, I am a firm believer in the potential of Sri Lankan English as a link language that could build bridges among the different speech communities in the country.

Allow me to begin my speech by thanking ‘The Social Architects’, for inviting me to be present on the occasion. It is, indeed, a privilege to be here. I have had the opportunity to skim read a couple of personal stories – though only in Sinhala, I grant, but I believe that these powerful pieces have the capacity to provide an interface – for the meeting of diverse minds, and hearts and spirits. I would like to congratulate TSA for this initiative as well as their other work in the field of ethnic and religious reconciliation.

A couple of days ago we marked eight years since the end of the war.

It is often claimed that time is a great healer. But I would like to question whether this is so for everyone?

Yes, certainly for some people – both in the divides of the South and the North, the war seems to have become a distant, though scarring memory. Life has gone on, been lived, people have moved to new cities, countries and continents; found new jobs and livelihoods, married and had children, begun to treasure and relish life once again.

But for others, specially those who have been directly affected in the North and East, those amongst the two fighting forces, and those lacerated by battle and bombardment, the war still remains a festering abscess. Life remains a daily struggle: to deal with loss – the loss of life, of family and loved ones; of occupations, positions, possessions, inheritances, and heritage. And most crucially, the loss of self – in body and mind.

Consequently, many Sri Lankans still remain deeply conflicted and wounded – given histories of intolerance and prejudices, insecurities of sporadic political violence, unaddressed structural inequalities, as well as frequent failures in governance to stem xenophobic campaigns – especially against the Tamils, Muslims and Christians of our country.

While there can be no return to cherished experiences and precious moments, we can however attempt to ensure that such injustices, injuries and atrocities do not take place again in this country – ever.

There is no doubt that the government has the greater responsibility to ensure that the requisite legal frameworks, policy implementation mechanisms, modalities and conditions are put in place – for peace to be sustainable, for truths to be expressible and acceptable, for justice to be transitional, and for reconciliation to be meaningful.

Moreover, the government has the onus to institute a new political culture that values free speech and diversity in opinion and dissent; that is proactive in preventing ethnic and religious violence, and that is able to hold fast to such aspirations – despite powerful forces and challenges of corruption and nepotism and militarization and commercialization and politicization.

And we are all aware of a number of initiatives by the government itself, as well as INGOs, NGOs and groups such as TSA towards meaningful reconciliation and sustainable peace.

However, we are all equally aware of other active forces that are working towards fulfilling their own venal self-interests, political agendas, quasi- religious aims, and parochial objectives – at the expense of peace and harmony.

In such a situation, we all have an equal responsibility in nationbuilding – even those of us who are not in government and who are not working in the field.

Remember, we all have the potential for self-initiative, for proactivity, and for resistance. Perhaps not on a grand scale but certainly at the level of the individual and the personal. In other words, when it comes to lasting peace and genuine reconciliation, do not forget that,

- we have the power, as individuals, to anticipate and be preemptive in what we say, do and practice;

- we have the power, as individuals, to advocate and self-initiate changes that are just and inclusive;

- and most importantly, we have the power, as individuals, to question and speak out;

- and to rise up and resist fear-mongering, prejudice and injustice as and when they occur.

If you really think about it, it only calls for everyday, ordinary, individual action – not only to prevent a culture of impunity but also to institute a culture of accountability.

Once again, congratulations and thank you.