Featured image courtesy Thuppahi

One year ago, on August 18, a new Parliament was elected on an ambitious premise of good governance. The public voted for change, and for an ambitious overhaul of the status quo.

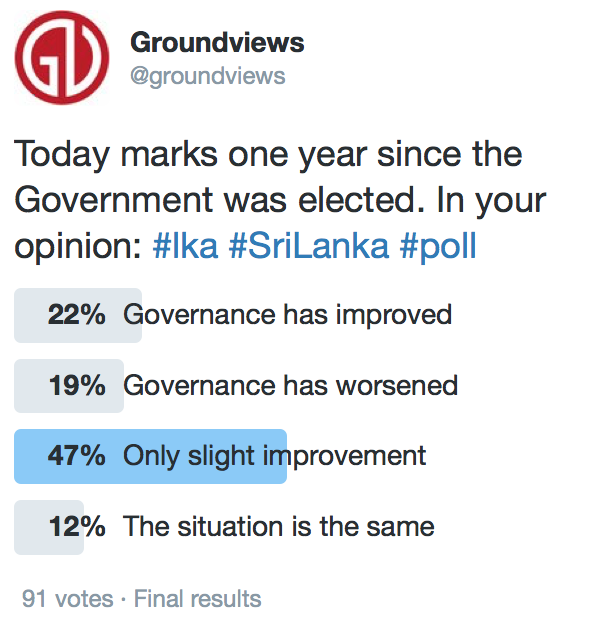

A year later, the public has mixed feelings about whether this new unity Government has succeeded. A Twitter poll taken by over 90 people showed that most felt there was only a slight improvement compared to previous years.

The poll is, of course, by no means indicative of national opinion, but is an interesting insight into what Groundviews’ readership feels about this Government’s performance. The poll shows that only 22% saw an improvement, and 19% felt the situation had worsened.

For context, Groundviews also spoke to members of civic society on their views about the current Government, in the context of their respective fields of work.

“While there was public expectation there would be a revolution, there has been more of a reconfiguration [of governance]. The achievements of this Government have had mixed results. We’ve seen a lot of legislative activity, but questions and doubts hanging over implementation,” said barrister and Executive Director of Transparency International, Asoka Obeysekara. “While bridging the gap can’t be done overnight, not enough is being done to change the public mindset.”

“Public consent for legislation is needed as well, so that the public can feel invested in it,” he continued. However, the signing of the Open Government Partnership in November showed a willingness to continue commitments similar to the pledges made during the Presidential election. The passage of the RTI Act too was positive, but a firm and committed civil society to ensure that the Government stuck to its promises was crucial at this juncture, he added.

Senior Lecturer at the Department of Philosophy & Psychology, at University of Peradeniya and former Secretary of the Ministry of Mass Media and Information, Charitha Herath said the current Government was better in terms of policy-making (through the passage of the 19th amendment and the RTI Act) but also concurred that implementation was weak and not result-oriented. As a result of this, people’s quality of life and purchasing power was affected. “The previous government over-reached in terms of their role in the social space. However this Government overestimates the role of the market, in a country like Sri Lanka in my view,” Professor Herath said. Certain essential services such as transportation, education, healthcare, environment and security should fall more under the purview of the state. There was a lack of clarity where the market should enhance their capacities as opposed to the state, and vice versa.

Science writer and development communication consultant Nalaka Gunawardene said that following the ‘decade of darkness’ of the Rajapakse regime, the benchmark had been set so low that the current government should not be measured by the same standards. “We must look at what was pledged and the practise. Perhaps it’s too soon to judge too harshly, but the first year sets the tone and should give us a sense of direction. It’s been very confusing, because this is a many-headed government,” Gunawardena said. While there were many promising steps made in reconciliation accountability, economic reforms were being announced but not pursued in an organised and systematic way. “This is putting political reform at stake,” he said.

Further, where the government was succeeding, they were not effectively communicating this to voters. The Government should be in charge of the narrative and tell its own good stories, rather than being reactive to the Rajapakse loyalists. “The Government needs to get its act together, far better than it has in its first year,” Gunawardena added.

Senior journalist and regional gender coordinator for IFJ Dilrukshi Handunnetti said that from a media perspective, Sri Lanka has made some progress, one year later.

“First, and perhaps the most important is the change in the atmosphere. For years, dissenting journalists had to fear for their safety and some have paid with their lives. The political culture that can take significant criticism and does not feel the necessity use the state machinery to silence journalists is perhaps the biggest achievement recorded by this government,” Handunnetti said.

Along with this there has also been some systemic change, albeit not entirely successful, within state run media institutions. Nevertheless, the space has been created for better journalism within these institutions, she added.

The introduction of the Right to Information Law was a significant step, particularly since the previous dispensation was not even inclined to discuss the positive attributes of such a law.

However, many challenges remain, she added.

“The sense of normalcy journalists experience is incomplete, if it is not shared by all. There cannot be surveillance of journalists in the North, a continuing practice – though reduced, according to journalists there. Also, there can never be a normal media landscape unless impunity ends. For this, the State must demonstrate sincerity by expediting the investigations on the murder, assault and abductors of journalists, charge those responsible and bring closure. So far, investigations have not been concluded and journalists, much like the war-affected civilians, await justice and reparation,” Handunnetti said.

The liberalisation of the state media should be completed through the promised process of converting state-run media houses to public service media institutions, as in many other countries. Otherwise, these institutions would remain in government control and could be used as political tools during election time.

Media reforms, including legal reform, will be incomplete unless implementing mechanisms are transparent and accountable. The implementation of RTI will be undoubtedly challenging given Sri Lanka’s culture of secrecy that dislikes proactive disclosure and conflicting laws such as the Official Secrets Act. As such, the entire body of legislation needs amendments for RTI to become a practical reality, Handunnetti said.

Human rights activist Ruki Fernando said the appointments to the National Human Rights Commission based on the 19th amendment, as well as that of the constitutional council, were positive steps as they had asserted their independence and taken definite policy positions in the field of human rights. “However the institution as a whole has a long way to go. They are state-centric and unresponsive, even incompetent. So while the Commissioner is independent the institution itself has not moved forward so much,” Fernando said.

The passage of the RTI Act was also positive, but there was minimal progress on transitional justice. The passage of the OMP Act was a significant milestone, but there were certain questions raised on the process behind it, leading to a lack of confidence. “The President and the Prime Minister have not been strong advocates of transitional justice, particularly among the Sinhalese.” As such, Fernando said the process was driven by international pressure, indicative of the fact that only Foreign Minister Mangala Samaraweera was a strong advocate of the process. “There has not been much outreach done locally.”

Violations too continued to occur. Human rights defender Jeya Kumari had been summoned yet again for questioning by the TID, while another human rights activist in the North had recently been threatened by a provincial UNP politician, not to get involved in issues pertaining to land. A culture of military surveillance and intimidation still persists, including the military acquisition of land, with the military still intruding on civilian activity despite recent assurances from Minister Samaraweera that the country would be demilitarised by 2017. “There is a lot of progress that still needs to be made in terms of human rights,” Fernando said.

For a more detailed look at the shifting perspectives on human rights over a year, a report was just released by INFORM Human Rights Documentation centre.

Freelance consultant Sharanya Sekaram spoke about youth issues, in the context of being appointed a Youth Parliamentarian in 2016, from the Minister’s List (i.e. directly appointed by the Prime Minister.)

“One key difference is that the Youth Ministry is no longer a separate entity, but falls under the purview of the Economic Development Ministry, under the Prime Minister. I saw this as positive, as it showed a direct commitment by the Prime Minister to the critical importance of engaging the youth,” Sekaram said.

This was a positive difference compared to previous years, she added, having engaged with former Youth Parliaments in the past. The 2016 Youth Parliament had also been representative, with quotas for student prefects, and university students in addition to the Minister’s list. The Youth Federation Club had ensured representation from the district to the national level as well.

However, Sekaram said that there were some missteps. As a prerequisite, members had to attend 3 day programmes which could have been better planned out and condensed. The members were put into different committees to debate various issues, with no consideration for past expertise. In practise, the Youth Parliament also ended up being almost a replica of the real thing, with Parliamentarians more interested in grandstanding, as opposed to applying their own belief systems. Most of the young Parliamentarians had never held jobs, but were attempting to make a career out of politics.

The result of this was young people who had perhaps worked on the private staff of Ministries but had otherwise never worked full-time engaging on issues like education, employment and urban development.

Women were also underrepresented – though less so than in Parliament. However men still took the primary position, with women mostly not speaking up on issues.

“I didn’t see an effort to address the root causes of the problems in Parliament – why some politicians play to the gallery but don’t adhere to personal belief systems, why the public does not hold Parliamentarians who do so accountable. While the programme is a fantastic opportunity to see what young leadership in Sri Lanka looks like, it could be better structured to address these issues.” Sekaram said. In this sense, the current government had a lot to do before ensuring that youth were properly and effectively engaged in Parliamentary process, going by the youth Parliament model.

From an economic perspective, Sri Lanka is yet to see a comprehensive development strategy from the Government, one year on, Chief economist from the Ceylon Chamber of Commerce, Anushka Wijesinha said.

“We have a statement by the PM last November, and we hear that a more fleshed out plan will be revealed by him later this month or next. That is important to articulate clearly to domestic and foreign stakeholders alike on what the government’s plans are, and bring in some consistency and stability,” he added.

There were positives – that Sri Lanka has reset foreign relations with strategically important countries over the past year. “This is probably the biggest win, in terms of government performance and its impact on business. Trade and investment is intrisincally linked to foreign policy and so good foreign relations helps advance trade and investment relations too,” Wijesinha said. The IMF package too helped give the government some breathing space needed for reform.

However, these gains were marred by policy uncertainty, particularly with regards to tax. Changes in taxes like VAT while announced haven’t gone through, while there was no roadmap for implementation for capital gains taxes. Foreign Direct Investment has not increased as expected, though there is considerable interest, as evidenced from visits from delegations from Norway, Chile, Mexico and Bahrain to name a few. “Converting that to results is now key,” Wijesinha said. The economy is also beginning to move away from the heavy dependency on public to private investment, which is a positive step, as is a much more open space for debate and even dissent on economic policy issues. “Whether [the discussion] is around the CBSL Governor or on tax policies…this is a very good thing. A contestation of ideas is needed to to come with a better path for the Sri Lankan economy.” Wijesinha said.

Yet despite the positive steps, many corporate executives were critical of progress made by the Government, a recent survey conducted by the Economist Intelligence Unit of the Ceylon Chamber of Commerce found. In fact, 49% of those surveyed gave the government a 2 out of 5 in terms of how successful their action has been on policy – though 41% also said they were optimistic the Government would deliver on its economic promise in around 4 years.

Interfaith issues has recently been in the news, particularly with the recent disruption of a peaceful vigil on equality. With this in mind, Groundviews spoke to visiting Fellow at the Institute of Advanced Islamic studies, Malaysia Amjad Mohamed-Saleem, who said “We have an opening up of the space for interfaith dialogue. It is welcoming that the President has appointed a new committee. ”

However, Saleem noted that the re-emergence of groups such as Bodu Bala Sena and Sinha Le in the public consciousness, as evidenced by the disruption of the Different Yet Equal vigil, highlighted deep-seated issues that needed to be addressed. “More work needs to be done at the grassroots [to address these issues]” Saleem said.

Senior Researcher with the Consultation Task Force on Reconciliation Mechanisms Chulani Kodikara said that from the perspective of women’s political participation, there has certainly been an improvement compared to the Rajapakse regime. “Many of us felt the Rajapakse era was regressive in terms of women’s rights – for 10 years there was a space emphasising family values over women’s autonomy.”

In this sense, Kodikara said she thought this government had made improvements over the past year, but the full extent was yet to be seen, given ongoing processes of constitutional reform and transitional justice. She added that at times, the Government showed a propensity to carry out such reform without adequately listening to society and women’s rights activists for real needs.

While the Local Government Authority Act of 2011 had given token attention to women’s participation in government, the new Government’s commitment to a 25% quota was an improvement. However there were some weaknesses, Kodikara pointed out. “Although the proposal does increase the number of seats awarded to women, it doesn’t challenge the incumbents.” Kodikara said. Rather, the current system empowered the party to select women candidates. “These women can’t go to the electorate and seek votes. This bypasses the electoral system.” While the new system would allow for more than 2000 women in local government, (compared to around 100 earlier) there was no explanation as to allocation of resources. A huge challenge was that under the proportional representation system, women had to compete at the Pradeshiya Sabha level, with men who often had much more access to resources. Being responsible to represent the whole Pradeshiya Sabha rather than the smaller wards was also an additional burden. “So the quota proposed is problematic, and we can’t be fully happy with it. For other issues, we will have to see until after the constitutional reform process to see whether they will be recognised.”

An uphill battle to be fought was the argument of “quality vs quantity.” “We always argue that these are two different issues – that women should have the right to be represented, irrespective of what they bring to the table.” Following on from this there was also a need to build women’s leadership skills moving forward, Kodikara said.

Dr Sepali Kottegoda, Executive Director of Women and Media Collective said the new Government’s promise of good governance offered a new platform and a different political context for women to advocate for gender equality. “The 25% nomination quota for women is a very positive step, and something we have been advocating for 20 years,” she said – even if it was only for nominations. “Sri Lanka doesn’t offer a social, political and economical environment to get voted in, just because our social development indicators are better than many in the South Asian region.” While it was positive that one woman had been appointed to the National Police Commission, the WMC wanted to see 30% representation of women in decision making bodies related to governance overall, she added.

Another positive step was the constitutional reform process, where the Government had attempted to be inclusive. “Women were given the space to voice issues, and many seized the opportunity in all districts, whether the North and East or the South. Citizens were told we can speak on any issue, even without expertise, which has never been the case before. We have never been invited to participate in such a process,” Kottegoda said. The WMC were till looking at how the law could be more gender responsive, and were looking at making submissions to the Fundamental Rights and the Law and order Committees.

The question now was to see whether the Government would take up the submissions made. Over the past year, the number of reported gang rapes, sexual and physical abuse appeared to have gone down, which either meant the media was not reporting on such cases, or the number of incidents had reduced, in relative terms, she added.

However, delays in the legal system with pursuing cases of violence against women, sex workers, and transgender people continued to persist, as the Attorney General’s department said they were overburdened. “People are languishing in jail, others are languishing waiting for justice. These cases are in limbo. The Attorney General’s department should find a solution to this,” Kottegoda said.

Reflecting the results of our Twitter poll, it’s clear that civil society feels that while there are some positives, there is a lot that needs to be addressed in order for the currently elected Government to live up to its promise of good governance. These issues, while multi-faceted and difficult to address, are nevertheless vital to be tackled in the coming year, and beyond. Not doing so will lead to an increasingly disillusioned populace, which could unravel the positive steps that have been made, particularly dangerous as Sri Lanka is only now taking the first tentative steps towards its own transitional justice process.