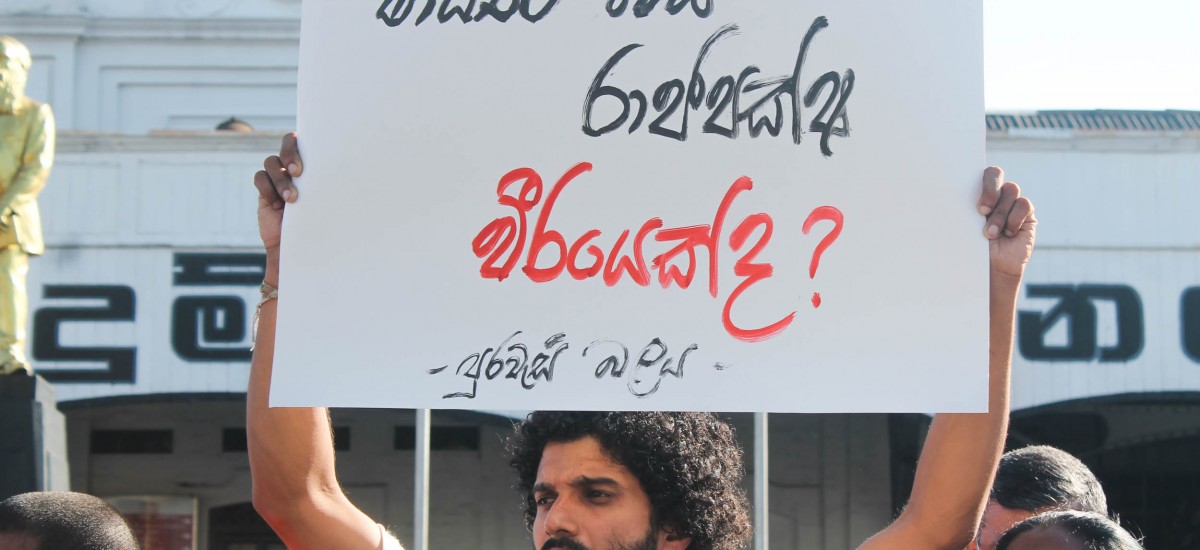

Image courtesy Sri Lanka Brief

During the past fortnight there have been many calls for the immediate repeal of the Prevention of Terrorism Act (PTA). Given the fluid and complex political context, and the upcoming parliamentary elections, it appears unlikely this will happen in the short term. However, there are a number of immediate measures the government could implement to illustrate its bona fides, and begin the process of re-building a relationship of trust with citizens, particularly Tamil speaking persons who constituted the majority of those arrested under national security laws. In addition to immediately reviewing the cases of those in detention and remand, and either releasing them or filing charges based on credible evidence, one of the other measures that could be taken is rescinding regulations issued under the PTA in August 2011 following the lapsing of the state of emergency.

According to section 27 (2) of the PTA, regulations made under the Act come into operation upon publication in the Gazette. Section 27 (3) states that regulations issued under the PTA have to be presented to Parliament for approval ‘as soon as convenient’ and any regulation that is not approved by Parliament will be deemed to be rescinded from the date of disapproval. It however makes no mention of what is considered a ‘convenient’ period, nor the status of regulations that are not presented in Parliament for an extended period. Unlike in other countries, in Sri Lanka there is no parliamentary committee on subordinate legislation to scrutinize the exercise of rule-making powers by the executive and ensure it is done within the power/authority of the executive, i.e. that it is not ultra vires and there is no abuse of delegated powers. Given the weak parliamentary committee system with the two standing committees on bills that are tasked with studying bills and proposing amendments largely inactive during the previous regime, the regulations were never presented in parliament.

Regulations issued under an Act should not widen the purposes of the Act or impose onerous restrictions not envisaged in the principal Act. However, the regulations issued under the PTA stipulate that a person can be held at a rehabilitation centre for a maximum period of 24 months, while the maximum period of administrative detention under the principal Act is 18 months. Additionally, since laws that restrict the liberty of citizens should be interpreted strictly, the Minister of Defence, it can strongly be argued, exceeded his authority by issuing said regulations.

According to the Supreme Court in Thavaneethan v. Dayananda Dissanayake, Article 15 of the Constitution which places restrictions on the operation and exercise of fundamental rights does not permit restrictions by executive action, i.e. by regulations, with the ‘sole exception permitted by…emergency regulations under the Public Security Ordinance because those are subject to constitutional controls and limitations’. Moreover, the decision states Article 15 (7) of the Constitution, which enables the imposition of restrictions on fundamental rights via law that is enacted in the interest of national security and public order, is not applicable to regulations made under the PTA or other statutes that are not subject to constitutional controls to which emergency regulations are subjected. Based on these factors it could be contended that the regulations issued under section 27 of the PTA are ultra vires.

Of these the regulation used most widely is the Prevention of Terrorism (Surrendees Care and Rehabilitation) Regulations No.5 of 2011. The term surrendee is used in the regulation since its scope of application is limited to those who surrendered voluntarily. However, in practice, many against whom there was inadequate, or no evidence to file charges, were sent to rehabilitation centres for periods of up to 2 years, a practice which continues to date. Even now, many who are detained under national security laws accept the rehabilitation option for they fear if they do not, they will be incarcerated indefinitely.

According to the regulation, being part of the rehabilitation programme does not preclude the person from being arrested for an offence. As there is no mention of the period within which the investigation should be concluded, prosecution could be initiated against a person any time before the conclusion of the period of rehabilitation. Hence, the surrendee has no certainty regarding his/her legal position, i.e. whether s/he might be prosecuted, until the completion of the rehabilitation period. There are no oversight or review mechanisms, with decision-making regarding surrendees resting entirely with the Secretary, Ministry of Defence. If the person is prosecuted and found guilty, the Court may order rehabilitation, the period of which is not stipulated in the regulation, and can be determined by the judge as part of the sentence.

In practice, sometimes persons who were held under a detention order (DO) without being produced before a judicial officer for a period of 18 months were later sent to rehabilitation for 2 years – the person was therefore moved from one form of arbitrary detention to another for a total period of 3 ½ years. There have also been instances of persons being moved from detention centres following the conclusion of the maximum period of detention (18 months), to a rehabilitation centre from which the person is moved to a detention centre again before the conclusion of the period of rehabilitation (anywhere from a year to 2 years), before being remanded. The total period of deprivation of liberty therefore exceeds 5 years, or continues to date.

Persons released from rehabilitation centres continued to be subjected to surveillance and monitoring by multiple state security agencies and the military. Since there are no legal provisions in national law that allow for such surveillance, this is cause for grave concern as it creates space for numerous rights abuses by security agencies. Nearly 6 years after the end of armed conflict, former combatants who have reintegrated into society should be allowed to continue their lives peacefully without the monitoring and interference of security forces. In exceptional circumstances, the recommendation of the UN Human Rights Committee- the independent body that monitors the implementation of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR)- which called for the adoption of national legislation that ‘clearly and narrowly defines the exceptional conditions under which former combatants could be subject to monitoring and surveillance’, should be followed.

Respecting and adhering to existing legal provisions and principles is another means through which the government can illustrate its intent to respect due process and the rule of law. For instance, the Presidential Directives on Protecting the Fundamental Rights of Persons Arrested and/or Detained issued by President Chandrika Kumaratunga, later re-issued by President Rajapaksa on 7 July 2006 and re-circulated by Secretary, Ministry of Defence, Gotabhaya Rajapaksa on 12 April 2007 to the Heads of the Armed Forces and of the Police, set out basic rules that have to be followed in relation to the arrest and detention of persons.

The Directives state that ‘that no person shall be arrested or detained under any Emergency Regulation or the Prevention of Terrorism Act No. 48 of 1979 except in accordance with the law and proper procedure, and by a person who is authorized by law to make such an arrest or order such detention’. The Directives require the arresting officer to:

- identify himself to the person being arrested or a relative or friend of such person

- inform the arrested person of the reason for the arrest

- allow the detained or arrested person to communicate with a relative or friend to inform of his whereabouts

- record the statement of the person arrested or detained in the language of the person’s choice

- allow the Human Rights Commission access to any place of detention and have access to any person arrested or detained

- inform the Human Rights Commission of every arrest and detention within 48 hours of the arrest

Article 4 of the Directives further states that when ‘a child under 12 or a woman is arrested or detained, a person of their choice should be allowed to accompany the child or woman to the place of questioning. As far as possible any child or woman arrested or detained should be placed in the custody of Women’s Unit of the Armed Forces or Police Force or in the custody of another woman military or police officer’. In addition to issuing arrest receipts to families, authorities should also inform families of any change of the place of detention. This is important since at present families, many with extremely limited economic means, travel long distances to prisons, detention or rehabilitation centres, only to find their family members have been transferred to another location. Further, lawyers should be allowed to confer with detainees in a private space without the presence of security officers, and the current practice that prohibits persons held at detention centres signing any document should be discontinued forthwith, since it prevents detainees from legally challenging their detention, for instance through a fundamental rights petition.

If as Foreign Minister Mangala Samaraweera stated, Sri Lanka wishes to leave the ‘culture of paranoia and debilitating fear psychosis’ and ‘re-establish ties equally with all nations’ instead of isolating ‘ourselves within a rapidly globalizing world’, one hopes the government’s respect for the rule of law and the rights of citizens will include respect for due process. Taking concrete action to review the cases of those detained under national security laws and ensuring their due process rights are respected would signal the regime’s commitment to being true to its stated vision which includes appealing to ‘the hearts and minds of…citizens in the North and East’. It is entirely possible to do this ‘without compromising on the integrity or security of the rest of the country’, a fact which has been recognized by the highest court in this country. For instance, in Weerawansa v. Attorney-General and Others the Supreme Court stated that constitutional safeguards were applicable even when implementing the PTA and pointed out that ‘it would be wrong to attribute to Parliament an intention to disregard those safeguards’, thereby giving precedence to the liberty of the citizen. Similarly, in Thavaneethan v. Dayananda Dissanayake, the Supreme Court interpreted the PTA strictly, finding that it did not impose any restrictions on the freedom of movement except in respect of specified persons, suspected of unlawful activity in terms of orders made by the minister. Moreover, the government can use as guidance the recommendations of the UN Human Rights Committee which calls for all security measures to be in compliance with the provisions of the Covenant and ‘contain clear prohibitions against arbitrary arrest and detention as well as clear safeguards against torture and protections of the rights to freedom of expression and association’, and the trials of those ‘arrested under emergency and/or counter-terrorism laws’ to be conducted by ‘independent and regularly constituted courts with adequate safeguards’.