Review of: Mahinde Thamai Iskole (Mahinda is the School!) by Sundara Nihathamani de Mel (Suratha Publishers, Mt Lavinia, Sri Lanka;

220 pages; LKR 600

I have never been able to understand why apparently grown Lankan men instantly turn so nostalgic — and sometimes completely incoherent — at the mere mention of their primary or secondary school.

Old school tie is evidently very strong among most of our men, often hilariously so. Thankfully women, many of who are just as loyal and grateful to their former schools, don’t descend to such immature behaviour.

As one with no emotional attachment to any of his old schools, I almost ignored Mahinde Thamai Iskole (Mahinda is the School). The book, released in mid 2012 and already into its fourth edition (wonder why?), is ostensibly a collection of its journalist-author’s reminiscences about Mahinda College, a leading boys’ school in Galle founded in 1892 as part of the Buddhist educational and cultural revival in 19th century colonial Ceylon.

Never judge a book by its cover! To my pleasant surprise, the book turns out to be much more than a potpourri of memories of a single school or a single generation. It is, without exaggeration, one of the most enjoyable Sinhala non-fiction books I have read in a long while.

Full credit goes to the author. Hailing from a literary family, Sundara Nihathamani de Mel is one of the finest writers in Sinhala journalism today. He is best known for his long-running satire column, Manige Theeruwa (Mani’s Column) which appears in Sunday Lakbima broadsheet Sinhala newspaper where, until a few weeks ago, he was chief editor (now promoted to Editorial Director).

But he is a great deal more. Sundara is probably the only bilingual journalist at the helm of a Sinhala newspaper today. In that sense, he is what my own journalism guru Gunadasa Liyanage (GuLi: 1930 – 1997) – himself a bilingual journalist, editor and author – once described as an ‘endangered species’ in Lankan journalism.

Swabhasha education, introduced on a wave of nationalism in the 1960s, has deprived us of men and women who can think and rise above their own particular race and language. Our society is poorer for it.

In fact, Sundara’s writing style is resonant of GuLi’s: simple, entertaining and highly anecdotal. Both write without any malice or ideological baggage. They are clearly attached to the personalities and events they describe, yet retain a sense of perspective. Many writers never achieve such maturity.

The book is distinctive for another reason: it is illustrated and designed by Dharshana Karunathilake, who draws perceptive cartoons in Sunday Lakbima and whose economy of words in social and political commentary is simply unsurpassable.

I first saw Dharshana in action when we were sixth grade classmates at Ananda College, Colombo, where he sometimes ‘got into trouble’ for caricaturising teachers during class. Now he makes an honest living lampooning political and social leaders.

Memory of the Nation

Sundara, who studied at Mahinda College from 1959 to 1971 (with a break during 1967-68), says his book isn’t a history of the school or an attempt at autobiography. True to form, it’s not even chronologically arranged, but that randomness holds its own charm.

What it does, brilliantly, is to offer a kaleidoscope of interesting nuggets about men and women (during co-ed days) who shared the formative years of their lives in school and are now scattered all over Sri Lanka – and beyond. Sundara chronicles these with measured pride of an old boy — but without the arrogance or insularity that most past pupils have about their school.

Some events captured in this book form an integral part of our recent history – what I see as the nation’s distributed and collective memory.

The best example is the story of what later became Sri Lanka’s national anthem. Its originator Ananda Samarakoon (1911 – 1962) was teaching music and art at Mahinda when he wrote and composed ‘Namo Namo Matha’ in October 1940. A few days later, he sang it for the first time with his students at the school’s Olctott Hall – that occasion is now marked by a commemorative plaque.

Another story is how a Mahindian cricketer performed the world’s only recorded instance of a wicketkeeper being responsible for all 10 dismissals in an innings. Teenager Welihinda Badalge Bennett achieved this feat – comprising six catches and four stumpings – while playing against Galle Cricket Club on 1 March 1953. It later earned him a place in the Guinness Book of World Records.

If these events had happened before the author’s own school years, he also relates some that he personally witnessed – or shaped. My favourite is how three 16-year-olds, including Sundara, published an innocuous school newspaper that earned the ire of education mandarins for being too forthright. In true babu style, they promptly banned its distribution. Which, in turn, made it front page news in a national political weekly…

The mighty provocation? Sundara’s hard-hitting editorial criticising the then Minister of Education I M R A Iriyagolla’s decision to phase out co-ed system in leading schools. The book reproduces that controversial piece in full, presaging the formidable writer within. (If only today’s school kids were bold enough to take on their own controversial minister…)

Nurturing Excellence

Sundara believes that Mahinda College has one of the most picturesque locations for any school in Sri Lanka. But more than its setting or buildings, the real beauty was how dedicated school teachers and principals nurtured generations of students to excel in curricular and extra-curricular activities.

That spirit of learning, caring and warmth are palpable in the pages of this book. From drama and scouting to debating and quizzing, Sundara and his contemporaries dabbled in many and varied pursuits. Behind every endeavour were teachers who worked way beyond their call of duty. At the time, it was the norm, not exception.

For those who can’t read this book in Sinhala, a rough analogy might be James Hilton’s 1934 novel Goodbye, Mr Chips. It tells the story of a much-beloved schoolmaster and his 43-year-long tenure at a British boys’ public boarding school. Except that this one is not fiction.

Indeed, the nexus isn’t that far fetched, considering that Mahinda College was built up by an extraordinary Englishman, Frank Lee Woodward (1871 – 1952), principal from 1903 to 1919. Although successive principals and teachers have added to it, the school is a living monument to this Cambridge Buddhist scholar.

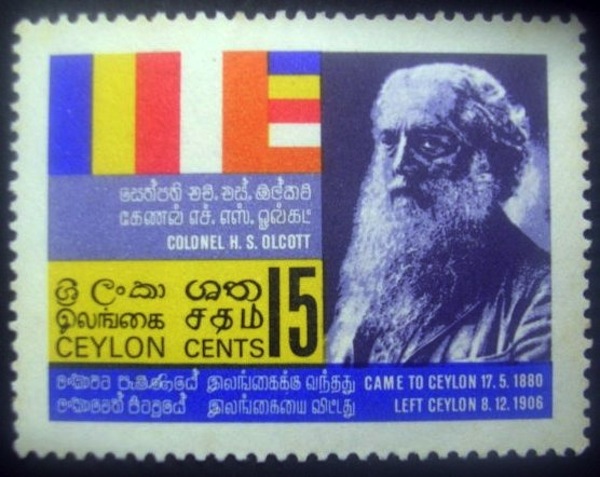

A decade earlier, an American civil war veteran Colonel Henry Steel Olcott (1832 – 1907) had founded Mahinda as part of a strategy to counter British imperialism by reviving indigenous education, culture and industry.

He was head of the Theosophical Society, a spiritual and philosophical organisation which he had co-founded in New York City in 1875. Joining him in this endeavour were fellow travellers Helena Petrovna Blavatsky (1832 – 1891), a Russian aristocrat, and William Quan Judge (1851 – 1896), an Irish lawyer cum occultist.

Uncommon Revolutionaries

The trio seem an unlikely group to take on the British Empire in its heyday. But these were no ordinary people. Driven by resolve, resourcefulness and moral outrage, they set in motion historical processes that inspired both the Indian independence struggle and Ceylon’s Buddhist resurgence.

Olcott and associates were not direct political activists like the ones who later confronted the British Raj. Instead, the theosophists quietly laid the foundation for self-reliance and self-confidence by setting up quality schools, reviving local arts and crafts, and encouraging industrial production. They unleashed long-term consequences they didn’t live to see – and haven’t yet been fully assessed by history.

We have since had several generations of ‘Children of Olcott’ coming out of dozens of schools set up and run by the Theosophical Society (before certain ‘sons of the soil’ nationalised them). Sundara has produced something akin to a scrapbook about a handful of such ‘Children of Olcott’ (and Woodward) who found their own place in the Sun in the second half of the twentieth century.

As a good journalist, he has written a first draft of history. Professional historians and sociologists can take it forward.

Meanwhile, my fondness for alternate history makes me wonder where we might be today if that extraordinary Yankee had decided to ‘mind his own business’. Whenever I hear political rhetoric against ‘Americans meddling in our internal affairs’, I ask myself: what if Col Olcott never came to Ceylon or India, and instead retired to his native Orange County in New Jersey for years of spiritual reflection?

And whenever I hear vitriolic attacks against “foreign-funded NGOs” in Sri Lanka, I can’t help thinking how the Theosophical Society was exactly that! And one with a hidden agenda, too!! Somehow, an unsuspecting (or smug?) colonial administration allowed it to operate.

So just imagine: if those few do-gooding and empire-subverting white foreign theosophists didn’t meddle in Ceylonese affairs over a century ago, our recent history could have been very different. Hmm…

Nalaka Gunawardene has survived three Lankan schools and two universities with (apparently) minimum brain damage. He now masquerades as a science writer and columnist, and blogs at: http://nalakagunawardene.com