Image from Iskra’s blog

Too long a sacrifice

Can make a stone of the heart.

From Easter 1916 by WB Yeats

“I want to grow up in a Northern Ireland where you can look at a sunset without wondering what they are bombing tonight”.

Immortality

I was disturbed to read comments on Colombo Telegraph by someone calling himself Thanga.[i]

“The question whether Prabhakaran is alive or dead is immaterial. Prabhakaran is part of Tamil history and part of Tamil psyche. He will be remembered by generations and generations to come. And liberation movements never die with their founders. As proof, books on LTTE leader Vellupillai Prabhakaran and the Eelam occupied an entire stall at the recent Book fare in Madurai book fair. ‘Over 25 books on Prabhakaran and the Eelam have been published in the last two years alone after the end of the Sri Lankan ethnic war. These books are attracting new readers,’ said the person manning the stall of Tholamai Veliyeedu. A 1000 page book on the life of Vellupillai Prabhakaran written by Pazha Nedumaran, an LTTE insider will be released soon. Prabhakaran is the only leader whose birthday is celebrated right around the globe in a grand scale! Prabhakaran was a brave, self-less and dedicated leader who lived by example. A leader who never slept on a mat or used a pillow!”

As recently as May 2011, in Tamil Nadu, MDMK chief Vaiko was saying the war for Eelam was not over; Prabhakaran was not dead and would emerge from hiding at the right time. According to Victor Rajakulendran, the LTTE remains a shining example, a “good history,” for all Sri Lankan Tamils to follow.

Irish Religiose Masochism

A miasma of religiose masochism hangs over Irish republicanism. Staying in Ireland as a child in the 1950s, I was acutely aware of the overlapping of the decades, the way the distant past lived in the present. In the 1950s, the 1920s lived on, as people still had pictures from that era on their walls. Shops still sold sentimental poems about the fallen. A fetid atmosphere of sanctity hung over shrines to the dead republican heroes.

A website gives a list of republicans executed, shot by the authorities or dead of hunger strike from 1916 to 1981. Some were killed by the British, some by Irish governments. Some committed suicide by starvation. They are all classed as “martyrs”.[ii]

Irish republicanism has an air of the pornography of martyrdom, of that self-flagellating kind of religiosity redolent of Iberian as well as Irish Catholicism. Often the Catholic church condemned the rebels but that did not prevent the movement portraying their fighters as ascetic saints, and venerating their dead in holy shrines.

Martyrdom was a principle aspect of the 1916 Easter Rising.

Padraic Pearse

The leading figure in the Irish Easter rising in 1916 was Padraic Pearse. He was a poet and playwright who founded a number of schools to which the Gaelicist intelligentsia sent their offspring to be raised in the high tradition of mythical hero Cuchulainn: “better is short life with honour than long life with dishonour”; “I care not though I were to live but one day and one night, if only my fame and my deeds live after me”.

Though not obviously a fighter, Pearse was enthused by the sight of armed Ulster loyalists and wanted to emulate them: “we might make mistakes in the beginning and shoot the wrong people: but bloodshed is a cleansing and sanctifying thing”. He developed a messianic and sacrificial notion that his cause was, through a symbolic loss of life, comparable with Christ’s sacrifice on the cross. Pearse expressed an ecstatic view of the energising force of the sacrifice of death in the First World War. He frequently celebrated the beauty of boys dying bravely in their prime, before the shoddy compromises of adult life corrupted them. Was there something homo-erotic in this, reminiscent of St Sebastian (as painted by Il Sodoma) as a gay icon? Pearse’s biographer, Ruth Dudley Edwards, wrote in an article entitled “The Terrible Legacy of Padraic Pearse” [iii]: “It would be frequently remarked of Pearse that he had no understanding of the mundane day-to-day concerns that precluded others from showing the same fanatical dedication to his successive causes: he lived and died for a people that did not exist.”

Blood Sacrifice

James Connolly was a more hard-headed, practical socialist who responded thus to an article by Pearse: “We do not think that the old heart of the earth needs to be warmed with the red wine of millions of lives. We think that anyone who does is a blithering idiot”. Connolly was a Marxist who wrote, “I have not the slightest tincture of [Catholic] faith left”. Nevertheless, Connolly was to write soon after: “Without the slightest trace of irreverence, but in all due humility and awe, we recognise that of us, as of mankind before Calvary, it may truly be said: ’Without the shedding of Blood there is no Redemption”.

Incredibly, the logistics of the Easter Rising were designed to maximise “bloody sacrifice”. Buildings were chosen for occupation, not to immobilize key government institutions, but to maximise injury to persons and property. Rebel HQ was set up in the General Post Office in the middle of the main shopping area. South of the River Liffey, parks, factories, bridges and public buildings were seized by small armed parties but with no plan of encirclement. Only about 1,600 rebels turned out in Dublin, with activity in the rest of the country limited to parading.

By the time Pearse surrendered after six days, only 64 rebels had been killed (including 15 executed). In the World War, 25,000 Irishmen died fighting as members of the British Army. The majority of the casualties in the Easter Rising , both killed and wounded, were civilians. Both sides, British and rebel, shot civilians deliberately, on occasion, when they refused to obey orders such as to stop at checkpoints. The British Army reported casualties of 116 dead, 368 wounded and nine missing. Sixteen policemen died, and 29 were wounded. All 16 police fatalities and 22 of the British soldiers killed were Irishmen. Rebel and civilian casualties were 318 dead and 2,217 wounded.

The rising was planned as a “blood sacrifice” for a society that had become apathetic. There were disagreements among the rebels. Eoin McNeill wished to proceed only on a basis of realistic hope of success rather than staking everything on a gesture of moral revivalism. He thought the blood- sacrifice option intellectually flaccid. Many, however, like 18-year-old medical student, Ernie O’Malley, who had no previous record of nationalist involvement, were strangely stirred by Pearse’s peculiar theology of insurrection. O’Malley became a key organizer and leader in the guerrilla war as well as one of its most prominent literary chroniclers.

The Easter Rising was not supported by public opinion in Ireland, and the immediate reaction afterwards was fury and disgust. Afterward, general incompetence on the part of the British government, and the arrests of thousands of men, some of whom were taken to England and Wales to be interned, only served to arouse hatred for the English among the population and to support the rebels’ propaganda.

The men who were executed were regarded as martyrs. The dead were prayed toas well as for. If the situation had been handled better by the British, the Sinn Fein movement could have received a severe setback. As an aftermath of the rising, about 50,000 British soldiers were stationed in Ireland which deprived England of much-needed men and equipment. Recruitment for the First World War in Ireland practically stopped, making a net loss to the firing line of 100,000 men. The threat of conscription further alienated the Irish.

A new revolutionary elite formed in detention and “a sentimental cult of veneration for the martyrs developed outside, as after previous failed risings. A settlement involving a good measure of Home rule had been likely even without the rising. The conspirators thus achieved their aim of reversing the movement towards Anglo-Irish reconciliation”[iv]. Throughout 1917, the Irish volunteers invited arrest and martyrdom and tried to disrupt the prison system by hunger strikes in pursuit of “political status”.

Terrorism was slow to develop and was mainly precipitated by brutal British methods of repression which forced Volunteers to band together for protection. There were no more than 4,000 armed activists and they had no hope of military success. Internment was introduced in 1920. The Black and Tans and Auxiliaries were also sent into Ireland in that year. Their reprisals included beatings and killings; they destroyed 53 creameries and ransacked many towns; in December 1920 they set fire to the centre of Cork City; on November 21, twelve football supporters were slaughtered at Croke Park in revenge for the assassination of fourteen spies.

Michael Collins and Éamon De Valera

Two of the Easter rebels escaped the firing squad and continued to polarise Irish politics for decades. Éamon de Valera, “The Long Fellow”, had been born in New York and had a Cuban father of Spanish descent so the British did not feel inclined to execute him as a traitor to the Empire.

Michael Collins, “The Big Fellow”, was not regarded by the British as important and he was despatched to Stafford prison and then on to Frongoch internment camp. He was back in Dublin by Christmas 1916. The guerrilla methods he soon developed were thought to have influenced Che Guevara (who, incidentally, had an Irish grandmother) and the Viet Cong.

When the British offered to negotiate a Treaty in 1921, De Valera engineered that Collins would lead for the Irish side. De Valera’s opponents claimed that he had refused to join the negotiations because he knew the outcome would be a partitioned Ireland and did not wish to receive the blame. Collins himself protested that he was not a skilled negotiator and that being seen in public would reduce his effectiveness as a guerrilla leader should hostilities resume. Reluctantly, Collins accepted the role of lead negotiator and signed the Anglo-Irish Treaty which set up an Irish Free State of 26 counties with dominion status within the commonwealth. The six counties of the north east remained in the United Kingdom. While it fell short of the republic that he’d originally fought to create, Collins concluded that the Treaty offered Ireland “the freedom to achieve freedom.” A little now, more later. Nonetheless, he knew that partition, would not be popular in Ireland. Upon signing the treaty, he remarked “I have signed my own death warrant.”

De Valera was unhappy that Collins had signed any deal without his authorisation. A civil war was fought on the basis that Collins had sacrificed a united Ireland. Though nominally head of the anti-Treatyites, de Valera does not seem to have been involved in any fighting and had little or no influence with the military republican leadership. Collins was secretly planning to launch a clandestine guerrilla war against the Northern State, while De Valera, in his own long years in power, accepted the status quo with Britain and executed and interned IRA die-hards who continued to fight for a united Ireland.

De Valera sent a personal note of congratulations to Subash Chandra Bose upon his declaration of the Free India government in 1943, although Ireland did not extend diplomatic recognition to it. Against the advice of some advisers, de Valera formally offered his condolences on the death of Hitler.

Éamon de Valera led his party, Fianna Fáil, to adopt conservative social policies, since he believed devoutly that the Catholic church and the family were central to Irish identity. De Valera died in 1975, a blind 93-year-old. One biographer, Tim Pat Coogan, sees his time in power as being characterised by economic and cultural stagnation. A younger historian, Diarmaid Ferriter, argues that the stereotype of De Valera as an austere, cold and even backward figure was largely manufactured in the 1960s and is misguided.

Collins died in 1922 at the age of only 31, in an ambush at Béal na mBláth (the Mouth of Flowers) near his home town of Clonakilty in West Cork. He was older than Jim Morrison but younger than Elvis. Collins’s memory lives on but can he be regarded as a martyr when he was killed, not by the British, but by his fellow Corkonians? He is certainly marketed to tourists as a “Lost Leader”.

Collins was big and handsome and charismatic. There were rumours of lovers including Dame Edith Vane-Tempest, Lady Londonderry, a famous political hostess. According to the memoirs of Derek Patmore, a writer and artist who was a close friend of Hazel Lavery, wife of the portrait painter Sir John Lavery, Collins was “the great love in her life”. A personification of Ireland modelled on Lady Lavery and painted by her husband was reproduced on Irish banknotes from 1928 until the 1970s. Sir John painted a portrait of Collins in full military uniform in his coffin draped in the Irish tri-colour.

Frank O’Connor, in his 1937 biography of Collins[v], paints a picture of a larger-than-life character, hot-tempered, violent, sentimental, respectful of elders, well-read, intelligent, and, despite his volatility, calculating and efficient. O’Connor was a distinguished writer of fiction, so one cannot tell how “creative” his picture is. The book is sympathetic to Collins which might be surprising as O’Connor (real name Michael O’Donovan) fought on the opposite side and was one of twelve thousand Anti-Treaty combatants who were interned by the government.

“The bulk of Collins’s time was not spent in action scenes. It was spent as a manager and administrator, whether as Minister of Finance or Director of Intelligence”.[vi] He was conscious of the advantage of maintaining a public image of a uniformed general commanding the national army but he was irritated at the mystical and neurotic worship of the republic.

O’Connor describes Collins thus: “This energetic man, who kept a file for every transaction, who insisted on supervising every detail and went nowhere without his secretary, bore very little resemblance to the Collins of legend and none at all to the revolutionary of fiction. Beside him, Lenin, with his theories, feuds and excommunications, seems a child, and not a particularly intelligent one. He ran the whole Revolution as if it were a great business concern, ignoring all the rules”.

Even in March 2012, the rivalry between Collins and De Valera lives on. In the Irish Senate, Fine Gael Senator Tom Sheahan recently asked, “Is it not ironic the way history repeats itself?” said, pausing for effect before adding: “Deputy Micheál Martin is not the first Corkman to be shot in the back by a de Valera.” The Senator’s mock concern for Fianna Fail leader Martin, who forced his deputy leader Éamon Ó Cuív – a grandson of de Valera – to resign because of his defiance on the party’s support for the fiscal treaty referendum, had the desired effect. Having got everybody into a state of high excitement, Mr Sheahan remarked mildly: “I will withdraw the comment which appears to have caused upset.”[vii]

That the question of who shot Michael Collins still has the ability to provoke a political row 90 years after the event is a testament to the significance of an event that played such an important role in the first year of the State’s existence.

Neil Jordan’s 1996 film Michael Collins implied that de Valera had a direct role in the shooting. Collins was portrayed as warm-hearted and passionate by the expansive Liam Neeson (love interest supplied by Julia Roberts as fiancée Kitty Kiernan) while De Valera was played slyly by that master of sinister, Alan Rickman.

Civil War

Most people, except the Northern Ireland protestants, were content enough with the Treaty. In the 26 counties, a few Republican intransigents like De Valera did not recognise its legality and provoked de-stabilisation by classifying MPs and judges, and even journalists, as legitimate targets for assassination. Far more people, including civilians, were killed in the civil war than were in the war for independence. David Fitzpatrick[viii] wrote in 1989: “ The violent challenge to the state then degenerated into a dolorous sequence of murders, robberies, burnings and kidnappings which has not yet ceased. So the state survived its painful baptism into a faith whose first article was the consolidation of state authority rather than the welfare of the nation. “

The Free State government responded with draconian measures such as summary execution without trial. Ex-comrades carried out seventy-seven such executions adding to “the litany of republican martyrs, and thousands of imprisonments created abiding bitterness”.[ix]

Three years after the end of the Sri Lankan conflict, there are still disputes about the number of dead. Ninety years after the end of the Irish Civil War, figures are still uncertain. The figures used by historians in the 1980s are now considered to be greatly exaggerated. A figure of over 4,000 does not tally with recent research which gives national army deaths at around 800.The Registrar General’s office estimates that in 1922 and 1923 there were 1,150 deaths classified as homicides, executions or shootings.

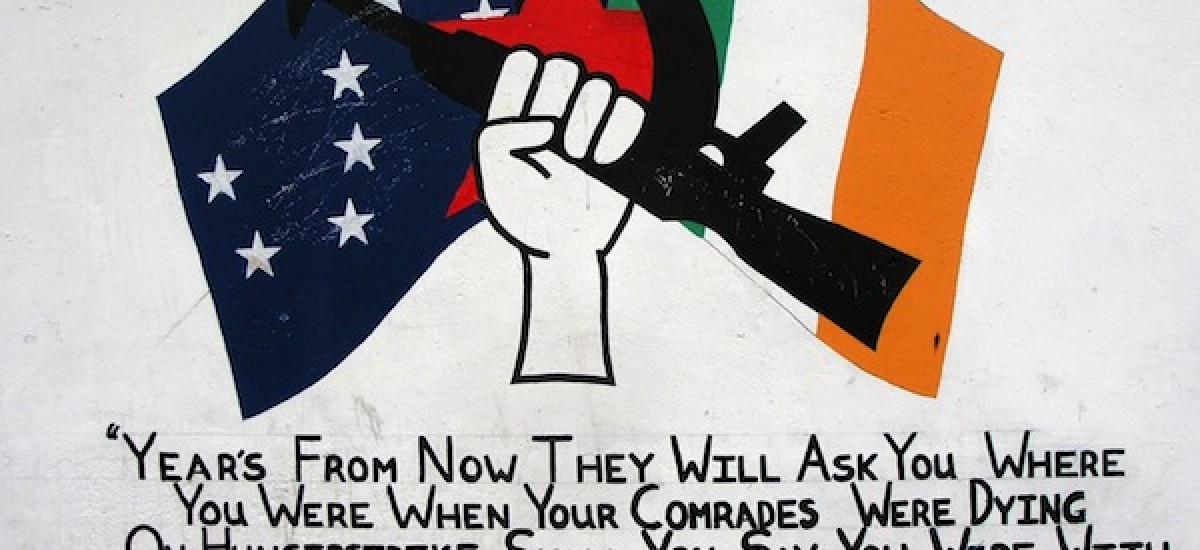

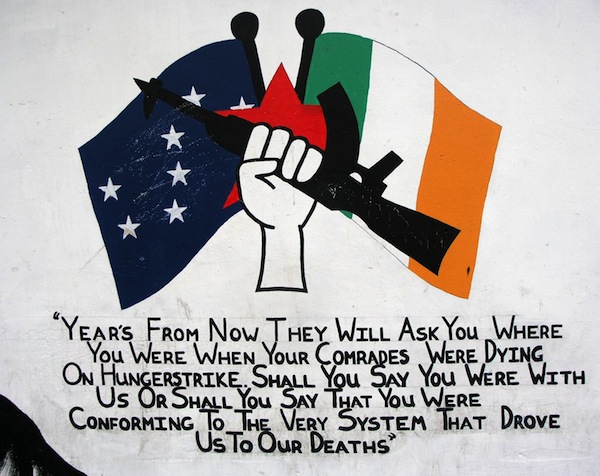

Hunger Strikes

I was amused at the usage in Sri Lanka (and Tamil Nadu) of the expression “fast unto death”. Generally, it is no more than a fast from breakfast unto lunchtime. In the Irish republican tradition, the term “hunger strike” is used and it often does end in a martyr’s death. Some scholars trace the Irish tradition of hunger striking back to Asian roots. The tactic was fully incorporated into the ancient Brehon legal system. Fasting in order to bring attention to an injustice was a common feature of early Irish society.

According to Roy Foster[x]: “Sinn Fein rhetoric capitalised on the drama of high-profile tactics such as [Thomas]Ashe’s hunger strike in 1917; significantly, a member of the [Catholic] hierarchy officiated at his funeral.” Like later Provisional IRA hunger strikers, Ashe was demanding special status as a prisoner of war. At the inquest, the jury condemned the staff at the prison for the “inhuman and dangerous operation [force feeding] performed on the prisoner, and other acts of unfeeling and barbaric conduct”

In October 1920, eleven republican prisoners in Cork Jail went on hunger strike at the same time. The Lord Mayor of Cork, Terence MacSwiney , died on hunger strike in Brixton prison. Attempts at force-feeding MacSwiney were undertaken in the final days. On 20 October, he fell into a coma and died five days later after 74 days on hunger strike. His body lay in Southwark Cathedral in London where 30,000 people filed past it. MacSwiney’s life and work had a particular impact in India. Nehru took inspiration from MacSwiney’s example and writings, and Gandhi counted him among his influences. Indian revolutionary Bhagat Singh, on hunger strike before his execution, quoted Terence MacSwiney and said “I am confident that my death will do more to smash the British Empire than my release”. Ho Chi Minh, who was working in London at the time of MacSwiney’s death, said of him, “A nation that has such citizens will never surrender”. MacSwiney himself wrote: “It is not those who can inflict the most, but those that can suffer the most who will prevail.”

The Provisionals’ leader in the 1970s, Sean Mac Stíofáin (who was baptized John Stephenson in Leytonstone, England, as a Catholic, despite the fact that neither of his parents was Catholic) announced melodramatically at his trial that he would be “dead within six days”. After four days, however, – amid rumours that he had been paying frequent visits to the prison showers – he agreed to take liquids (including soup and sweet tea). His hunger strike led to tumultuous scenes in Dublin and protests outside the Mater Hospital where he was visited by the then Catholic Archbishop of Dublin, Dr Dermot Ryan, and his predecessor, Dr John Charles McQuaid. He was ordered off his hunger strike by the Army council after 53 days and was never to regain his influence.

Bobby Sands

Bobby Sands was the first of ten Provisional IRA prisoners to die during a hunger strike in 1981. The ten men survived without food for 46 to 73 days, taking only water and salt, before succumbing. Sands’s death resulted in a new surge of IRA recruitment and activity. International media coverage brought attention to the hunger strikers, and the republican movement in general, attracting both praise and criticism. Sands wrote a book on the subject, One Day in My Life and was the subject of a film, Hunger.

The Physical Force Tradition

Charles Townshend[xi] wrote that the Easter Rising was: “A manifestation of violence as politics. It was not the prelude to a democratic national movement which led in turn to the establishment of a ‘normal’ constitutional national polity. It was, rather, a form of politics which may be called ‘demonstration politics’, the armed propaganda of a self-selected vanguard which claimed the power to interpret the general will. Cathartic action was substituted for methodological debate; ideal types replaced reality; symbols took on real power. The Irish Republic, ‘virtually established’, would not now go away, yet it could never exist- not, at any rate, as the ‘noble house’ of Pearse’s thought”.

Conor Cruise O’Brien pointed out 30 years ago that Pearse and his colleagues believed they were entitled , although they were but a small unelected group of conspirators in a democratic country, to stage a revolution in 1916 in which many innocent people were killed – entitled because their judgement was superior to that of the population at large. For generations afterward, the IRA used the same argument, seeing themselves as the heirs of Pearse. Why was it right for the 1916 martyrs, O’Brien asked , yet wrong for the Officials, the Provisionals and now the Continuity and Real IRA to emulate them?

Former Provo, Danny Morrison, explained in a Pearse documentary Fanatic Heart, that Pearse’s rhetoric was useful to the Provos when they were making war, but is inconvenient when they are trying to make peace. Did the 1916 Rising set an unfortunate and tragic precedent?

Ruth Dudley Edwards: “With another generation of intransigents murdering in our name, isn’t it time we contemplated the heresy that the 1916 rebellion was misconceived and without justification, and that the physical force tradition in the 20th century has been an unmitigated disaster?”

Proportionality and Presumption: “a self-selected vanguard which claimed the power to interpret the general will”.

In the 1960s in Northern Ireland there was a legitimate, non-violent, civil rights movement dedicated to addressing the grievances of the Catholic population. The movement was hijacked by the hard men of the Provisional IRA. Although they assumed for themselves the role of protectors of the Catholic population, their agenda was to emulate the republican martyrs of yesteryear and to fight for a united Ireland. This degenerated into atrocity and criminality[xii]. Despite the undoubted success of the Good Friday Agreement[xiii] a handful of unelected die-hards do not want peace. They want to create new martyrs for Ireland .

Is there an inevitable regression from Northern Irish Catholics suffering discrimination, to innocent English (and Irish) people being blown to giblets while enjoying a drink with friends?

The film critic Mark Cousins has noted the current prevalence of vengeance as a theme in movies. He noted that one of the questions of our time is how a tribe that has been harmed finds peace. The answer for some filmmakers (presumably it makes money) seems to be to return harm to those who harmed. Such movies seem to give comfort by ventilating an audience’s feelings of impotence.

LTTE Exploitation of Death

“The LTTE capitalised on the emotional force of death and its commemoration to arouse support for the cause of Eelam and the LTTE. From the very outset in 1983 they exploited the death of their fighters in action by organising funeral processions, even clandestine ones, to incite people against the enemy and to draw them to the LTTE cause. Then, circa 1989 they even took the radical step of claiming the primary rights over the corpses of all their fighters; and decreeing that even those of Saivite faith should be buried not cremated… The institutionalisation of commemoration was gradually expanded over the years that followed and rendered as evocative as it was systematic. This event was augmented by a series of other rites of homage recognising key Tiger heroes and heroines, in effect generating a ritual calendar of ten ceremonies every year”.[xiv]

The LTTE were noted for inventing suicide bombing. Black Tigers could have a noble death sacrificing themselves for the cause. They carried cyanide capsules around the neck so they would not be captured alive. It has been noted by many that Prabhakaran did not take this route himself. One recent comment on Groundviews by someone critical of the GOSL: “When the moment came he did not have the guts to commit suicide even though he recommended it heartily to his underage combatants.”

Choosing Martyrdom

Armchair warriors and conflict junkies get some satisfaction from keeping anger alive and espousing vengeance as if life were a movie, the pain of the wounded and incarcerated a matter relevant to their own egos. Some warriors use real, deadly bombs. The Real IRA as of June 2005, was believed to have a maximum of about 150 members. One of the organisation’s founders, the sister of Bobby Sands, Bernadette Sands-McKevitt, said: “Bobby did not die for cross-border bodies with executive powers. He did not die for nationalists to be equal British citizens within the Northern Ireland state”.

I was in a bar in Cork city centre when news of the Omagh bombing was on the TV. Everyone in the bar wept unashamedly. Only a tiny minority wants such brutality. On Saturday 15 August 1998, 29 people died and approximately 220 were injured as a result of a car bombing carried out by the Real IRA in the town of Omagh, in County Tyrone. The victims included people from many different backgrounds. Among them were Protestants, Catholics, a Mormon, nine children, a woman pregnant with twins, two Spanish tourists and other tourists on a day trip from across the border in the Republic of Ireland. Bobby may have made a conscious decision to “die for Ireland”. The victims of Omagh did not.

No-one has been successfully criminally convicted of the bombing but a retrial of a civil case brought by relatives of some of the victims against Colm Murphy and Seamus Daly has been set for October 3 2012. In June 2009 Michael McKevitt, a convicted Real IRA leader serving a 20-year jail sentence, and Liam Campbell were found liable for the bombing in a civil ruling. Mr Justice Morgan, now Northern Ireland’s lord chief justice, ordered them to pay £1.6m in compensation.

As I write this I am reading reports of IED bombs being disabled in Cork, Belfast and Dublin in the past week. The Army Bomb disposal Squad have had five call-outs in a week. Action and reaction – will the circle be unbroken?

Revolutionary leaders presume a lot. Pearse might nobly say: “I care not though I were to live but one day and one night, if only my fame and my deeds live after me”. Thanga might say: “Prabhakaran was a brave, self-less and dedicated leader who lived by example. A leader who never slept on a mat or used a pillow!” Did Prabhakaran ever ask those who are shown in the horrific Channel 4 images if they wanted to be martyrs? Was there a referendum on martyrdom, a focus group?

In his acceptance address to the Gandhi Foundation when receiving their 2008 Peace Award, my friend Harold Good, who played an important role in the Northern Ireland peace process, quoted a child who wrote: “I want to grow up in a Northern Ireland where you can look at a sunset without wondering what they are bombing tonight.” Harold commented: “Today our children see sunsets instead of bombs. As a community we have faced and accepted realities; engaged in dialogue; achieved consensus; accepted compromise and witnessed the signs and symbols of peace.” Harold told me recently that he follows events in Sri Lanka with great interest and concern.

Read the comments on the Channel 4 website. My feeling is that most of the hatred is coming from people who do not live in Sri Lanka. Is this hatred and lust for revenge healthy or productive?

Human beings suffer,

They torture one another,

They get hurt and get hard.

No poem or play or song

Can fully right a wrong

Inflicted or endured.

…

History says, Don’t hope

On this side of the grave.

But then, once in a lifetime

The longed-for tidal wave

Of justice can rise up,

And hope and history rhyme.

So hope for a great sea-change

On the far side of revenge.

Believe that a further shore

Is reachable from here.

Seamus Heaney The Cure at Troy

Enough of martyrs. Enough of revenge. Let us hope a further shore is reachable, in Sri Lanka and Ireland.

[i]http://colombotelegraph.com/2012/02/21/victor-rajakulendrans-tirade-at-the-exposure-of-pirapaharans-admiration-for-hitler/

[ii] http://www.irishfreedom.net/IRPA/Background%20Material/Irish%20Republican%20martyrs.htm

[iii] http://www.independent.ie/unsorted/features/the-terrible-legacy-of-patrick-pearse-348632.html

[iv] Fitzpatrick op cit.

[v] The Big Fellow: Michael Collins and the Irish Revolution

[vi] Historian John Regan in Cork Examiner 26 February 1997

[vii] http://www.irishtimes.com/newspaper/frontpage/2012/0302/1224312635711.html

[viii] Fitzpatrick op cit.

[ix] Modern Ireland 1600-1972, Foster, RF, Allen Lane, 1988

[x] Foster, op cit

[xi] Political Violence in Ireland: Government and Resistance since 1848, Townshend, Charles, Oxford 1983.

[xii] http://pcolman.wordpress.com/2012/02/13/terrorism-business-politics-and-ordinary-decent-criminals/

[xiii] The Collins Press; New Upd edition (1 Mar 2008)

[xiv] Michael Roberts