Rwandan President Paul Kagame. Image courtesy Wikipedia

For many of us in Sri Lanka the only thing we’re really likely to know about Rwanda is that a genocide happened there in 1994. We probably don’t know who killed whom, for what reason or even how many people died. While the Genocide is a watershed moment in Rwanda’s history, in this article my interest is in highlighting some thoughts on Rwanda’s present and future in order to suggest some ideas for Sri Lanka’s post-war progress.

Rwanda after the Genocide

After the Rwandan Patriotic Front wrested control of the county in July 1994, Rwanda was a country in ruins. It had lost nearly one million people, most of the country’s economic affairs had come to a complete halt and many of the most senior government officials had fled the country in fear of reprisals for their role in the Genocide. It was a crucial moment for Rwanda and it had to either sink or swim. A small comparison of a few key indicators is presented below in order to provide an instructive picture of the situation that Rwanda faced.

| Indicator | Rwanda in 2000

(6 years after genocide) |

Sri Lanka in 2010

(2 years after civil war) |

| Per Capita Income (GDP) US$ | 290 | 2057[i] |

| Poverty Rate | 64% | 8.9%[ii] |

| Life Expectancy | 49 years | 74 years[iii] |

It seems clear that in comparison to Rwanda, Sri Lanka’s position after the war appears to be quite strong. However this does not mean that Sri Lanka can afford to be complacent about the challenges that it faces in rebuilding a country that has been torn apart by 30 years of civil war. Indeed a bury-our-heads-in-the-ground-and-hope-for-the-best style approach to these challenges while easier in the short term, may cause more conflict and expose further fissures in the Sri Lankan social fabric in the future. Sri Lanka would do well to learn from Rwanda’s approach to rebuilding a country in the aftermath of a war. Although there are many issues that are instructive for Sri Lanka today, I would particularly like to focus on the Government of Rwanda’s Vision 2020.

Rwanda Vision 2020

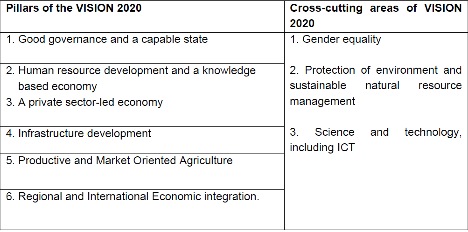

Rwanda’s vision 2020 is a document that expresses the vision of the Government of Rwanda for the development of “a modern, strong and united nation, proud of its fundamental values, politically stable and without discrimination amongst its citizens.”[iv] It seeks to make Rwanda a middle income country with specific short term, medium term and long term goals that it hopes to achieve by 2020. Vision 2020 is built on six pillars and three cross-cutting themes. (see image)

It is also important to highlight the process through which the Government of Rwanda finalized this vision. Vision 2020 was a result of wide-spread national consultations that took place over a period of two years. The Government of Rwanda developed a draft of its vision and then reached out to the people of the country to hear their views on this vision for two years before finalizing it as a document called Rwanda Vision 2020. As a result of their national consultations, most of the ordinary citizens in Rwanda speak easily of vision 2020 and where they want their country to be in 2020.

What is also noteworthy about Rwanda’s Vision 2020 is its very frank and self-critical reflection on the position in which it was in when this vision was developed. A significant portion of the document deals with the history of Rwanda and the challenges it faced at the time. A very frank assessment also enables the development of a stronger vision for a country as it makes no assumptions about the starting point of its journey towards a shared goal.

Whither the Sri Lankan Vision?

In Sri Lanka we are yet to have a broad discussion on what kind of a country Sri Lanka would be by 2030. What is our vision for the next 20 years? Is it possible for a deeply divided society such as ours to have a “national” vision? What would our economy look like? What sectors will it be based on? Do we possess a vision for a plural and multi-cultural Sri Lanka that incorporates the concerns and expectations of all social groups in Sri Lanka? What kind of a Government would we have? Will our Parliament be seen as a progressive space for innovative law making? Would our judiciary be as progressive as the current Indian Supreme Court? These are only a few of the questions that a broad national vision would have to grapple with.

As much as the development of a national vision should be a question that requires serious thought, (if we agree that a national vision can be developed) serious consideration should also be given to the process through which this vision is developed and finalized. Would we consult people from different walks of life, different social groups and areas of the country in the development of this vision? Also whose vision would we give the most prominence to and on what basis would we decide which ideas should be part of our national vision and which ones shouldn’t?

Furthermore, are we willing to be frank about our current position? Economists constantly point to the unrealistic statistics and achievements trumpeted in the development of economic policy. Similarly it is also worth asking ourselves as to whether we in Sri Lanka are ready to be frank about our current positions and realities.

It’s important to realize that a broad inclusive process of consultation and dialogue in seeking to present a national vision not only works to develop it but because of their contribution, gives people across the country ownership and commitment towards achieving this vision. Developing a national vision forces us to ask ourselves some very tough questions about where we stand and where we want to be and who is really important to the country and why.

Governance and Development

Another important lesson to be learnt from the Rwandan Vision 2020 document is the emphasis placed on governance in achieving this vision. The fact that governance is the very first pillar that the vision is built on underlines the importance of sound governance policies as being the catalyst for a serious economic and social transformation of a country.

The country is committed to being a capable state, characterised by the rule of law that supports and protects all its citizens without discrimination. The state is dedicated to the rights, unity and well-being of its people and will ensure the consolidation of the nation and its security… The State will ensure good governance, which can be understood as accountability, transparency and efficiency in deploying scarce resources. – Rwanda Vision 2020 [v]

Are the state structures that exist in Sri Lanka transparent, accountable and efficient in deploying our scarce resources? Do we know what laws are being discussed in our Parliament? Do we know how laws are promulgated and what is said during our Parliamentary debates? Or instead do we take the idea of a social contract (electing people to govern on our behalf) too seriously and while complaining, do little to hold our MP’s accountable for the decisions they make on our behalf? Do the structures that we have in place make it easier or more difficult for us to do this?

What about our Future?

If we are to begin a serious process that will culminate in the development of a national vision we need to be willing to ask ourselves and our representatives the difficult questions such as the ones that I have raised above. It is now more than two years since the LTTE was defeated on the shores of the Nanthikadal Lagoon but we are yet to begin a serious process of self-reflection and consultation on the kind of country we want to build for ourselves and for our children. As much as we celebrate the achievements in the past, it is equally important to start the task of building our future. And a future cannot be built if we have no sense of direction or conception of where we want to go and how we will get there. The longer we wait the more distant the proposition of a shared future becomes… having known thirty years of war because of this, are we really willing to take that risk again?

[i] Central Bank of Sri Lanka (2010). Key Economic Indicators in Central Bank Report < http://www.cbsl.gov.lk/pics_n_docs/10_pub/_docs/efr/annual_report/AR2010/English/3_KEI.pdf>

[ii] Department of Census and Statistics (2011). Poverty Indicators < http://www.statistics.gov.lk/poverty/PovertyIndicators2009_10.pdf>

[iii] Central Bank of Sri Lanka (2010). Sri Lanka Socio-Economic Data 2010. < http://www.cbsl.gov.lk/pics_n_docs/10_pub/_docs/statistics/other/Socio_Econ_%20Data_2010_e.pdf>

[iv] Ministry of Finance and Economic Planning (2000), Rwanda Vision 2020. Kigali: Ministry of Finance and Economic Planning < http://www.minecofin.gov.rw/webfm_send/1700>

[v] Ibid