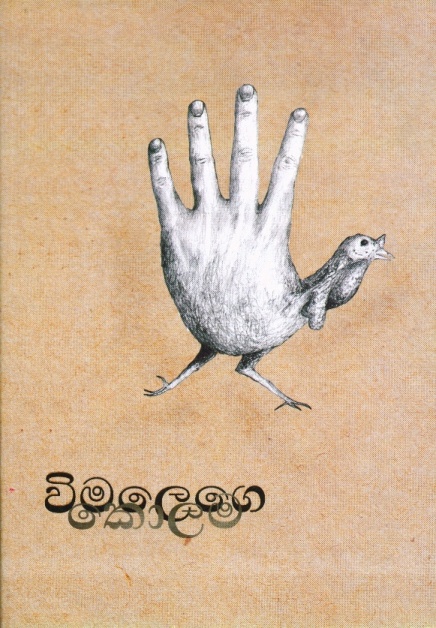

Review of Wimalege Colama (Wimale’s Column), a collection of satirical columns by Wimalanath Weeraratne

Sinhala; 232 pp; Author publication; September 2010

Political satire is nothing new: it has been around for as long as organised government trying to keep the wielders of power in check. Over the centuries, it has manifested in many oral, literary or theatrical traditions, some of it more enduring — such as Gulliver’s Travels and Animal Farm. And for over a century, political cartoonists have also been doing it with such brilliant economy of words. Together, these two groups probably inspire more nightmares in tyrants than anyone or anything else.

Today, political satire has also emerged as a genre on the airwaves and in cyberspace, and partly compensates for the worldwide decline in serious and investigative journalism. Many mainstream media outlets have become too submissive and subservient to political and corporate powers. Those who still have the guts often lack the resources and staff to pursue good journalism.

If Nature abhors a vacuum, so does human society — and both conjure ways of quickly filling it up. Into this ‘journalism void’ have stepped two very different groups of people: citizen journalists, who take advantage of the new information and communications technologies (ICTs), and political satirists who revive the ancient arts of caricaturisation and ego-blasting.

Both came from the periphery and challenged the status quo. And their rise in numbers and influence has not been universally hailed. Old school media professors just don’t understand (or can’t believe!) how anyone could produce good journalism without professional training, official accreditation or payment. And there still are purists who complain that political satirists blur the traditional demarcations between news, commentary and entertainment.

But in these topsy-turvy times, can we afford to insist on such all-or-nothing positions? If the mainstream news organisations don’t live up to our high expectations of news reporting and commentary, we should be grateful that some satirists and comedians are increasingly doing that job — and reasonably well, too. I would any day prefer a satirist taking on serious topics than a news anchor or reporter trying a comedian act.

Other media watchers and researchers share this view. A recent book, titled Satire TV: Politics and Comedy in the Post-Network Era (co-edited by Jonathan Gray, Jeffrey Jones and Ethan Thompson; NYU Press; 2009) told us why we now have to take satire TV seriously — it has become the bearer of the democratic spirit for the post-broadcast age.

As the book’s introductory blurb noted, “Satirical TV has become mandatory viewing for citizens wishing to make sense of the bizarre contemporary state of political life. Shifts in industry economics and audience tastes have re-made television comedy, once considered a wasteland of escapist humour, into what is arguably the most popular source of political critique. From fake news and pundit shows to animated sitcoms and mash-up videos, satire has become an important avenue for processing politics in informative and entertaining ways, and satire TV is now its own thriving, viable television genre. Satire TV examines what happens when comedy becomes political, and politics become funny.”

In Sri Lanka, we haven’t yet reached such high levels of political satire on television. But our cartoonists have long perfected the art — to me, the finest current example is Camillus Perera, the creator of such inimitable characters like Siribiris and Gajaman. Over the years, we have also had talented and indomitable political satirists like Tarzie Vittachi (Fly-by-Night), Sirilal Kodikara (Ranchagoda Lamaya) and a few others occasionally brightening up our otherwise hard times.

Joining this long and colourful tradition is an unassuming and seemingly innocuous satirical column that started appearing in the Ravaya Sunday Sinhala newspaper in late 2008. Its author, Wimalanath Weeraratne (WW for short), is a journalist on its editorial staff. He has just collected the best of his columns published between November 2008 and August 2010. The book is called, simply, Wimalege Colama (Sinhala for Wimale’s Column).

This book belatedly assigns a name to the column that started without any fanfare and continues so to-date: it carries no branded name or graphical masthead. Unusually for such writing in today’s Sri Lanka, the writer signs it with his own full name.

But if the column comes with too little sizzle, it offers plenty of steak. Every week, it takes off from a current news event or topical issue, and then builds an entirely plausible scenario that is both hilarious and provides piercing social commentary. Every reader gets some instantaneous comic relief, but the real meanings and messages often sink in later. In that sense, this column is a akin to the street theatre performances created by the late Gamini Hattotuwegama — hilarious, highly nuanced and totally irreverent.

No Sacred Cows

WW doesn’t beat around the bush. There is no disguise in his stories’ setting or characters. They all happen in contemporary Sri Lanka, and not in some imaginary this-land or that-land as invoked by other, more cautious satirists. There is also no innuendo or other literary or dramatic ploys. The characters are all living and known persons, appearing under their own names. Call these the modern-day tales of intrigue from the King’s Palace.

The ‘cast’ is led by no less than the incumbent President, and includes his politically active brothers, prominent Cabinet Ministers, senior officials and political adversaries. The first lady and other members of the first family get honourable (and sometimes not-so-honourable) mentions. Guest appearances are made by leading film actors, authors, newspaper editors and other public figures. The Veddah chief, Uru Warige Wanniya, once featured prominently, as did the UN chief Ban Ki-Moon.

The only fictitious characters are the ferocious First Cat and the garrulous First Parrot. They both dabble in the affairs of the state, and presidential public relations when the President is occupied (or sleeping). On second thoughts, they are not so fictitious after all…

The storylines are both diverse and daring. Among my favourites is when the President suddenly, inexplicably, turns into a cockroach for 24 hours. The story, reminiscent of Frank Kafka’s famous story The Metamorphosis (1915), exposes the duplicity of the numerous sycophants surrounding the leader. Another interesting story chronicles what (probably) transpired when police criminal investigators arrested an astrologer who predicted ‘bad times’ for the President and his government. (How come the soothsayer didn’t foresee his own imminent arrest?)

One column, first published in late 2009 when tensions between the government and General Sarath Fonseka were rising, imagined the President inviting all the notable Saraths of the land to a big dinner party at the presidential abode, Temple Trees. The gathering leads to some hilarious exchanges.

We find WW’s metaphors and analogies so funny because they are so apt. He once likened the Cabinet of Ministers to a primary classroom where their teacher (President) struggles to keep them focused and productive. Using the format of ‘Are you smarter than a Fifth Grader’ TV game show, the writer plays on the known foibles and idiosyncrasies of key ministers.

Inspiration for the weekly column has come from a variety of sources. The period 2008 – 2010 has been particularly turbulent and eventful in Sri Lanka, providing our satirist ample choice of topics ranging from the last stages and end of the civil war and frequent elections to political gymnastics and trade union agitations. By far the biggest single source is the President himself — WW feasts on his public statements, frequent lunch/dinner hosting, foreign visits (to unusual destinations like Burma, Libya and Ukraine) and other proclivities.

Psycho analysts and social critics can have a field day discussing WW’s take on various individuals and social institutions. Well, at least he is an equal opportunity basher — there are no sacred cows in his parallel universe. He lampoons politicians of all hue and colour with equal gusto. He frequently takes on the leading artistes, intellectuals and businessmen. And when the need arises, he also doesn’t spare the men in khaki (military) and men in saffron (Buddhist monks), two social institutions that most media in Sri Lanka treat with deference.

Medium is the message

In today’s Sri Lanka — which some spoilsports among us worry is turning into a ‘guided democracy’ a la Malaysia — the WW column is perhaps the last one of its kind. But the fact that it still stands, and seemingly thrives, is by itself a cause for celebration.

Satire is a hard act at the best of times, and making fun of those wielding power can be especially hazardous when big egos are bruised or vested interests feel threatened. Very few of our satirists directly take on the incumbent head of state, whoever is holding office. Political cartoonists venture a bit further, but they too observe self-imposed limits. (A generation ago, cartoonists gleefully caricaturised the executive Prime Minister as a raging bull. Would anyone attempt that today?)

In the highly acquiescent media environment in today’s Sri Lanka, WW’s column could appear only in the Ravaya. It is an extraordinary publication that has, for nearly a quarter of a century, provided a platform for vibrant public discussion and debate on social and political issues. It does so while staying aloof of political party loyalties and tribal divisions. While it cannot compete directly (for circulation) with newspapers published by the state or press barons, this sober and serious broadsheet commands sufficient influence among a loyal and discerning readership.

Published by a company owned by journalists themselves, Ravaya is almost unique among Lankan newspapers for another reason: its columnists and other contributors are allowed to take positions that are radically different from those of its formidable editor, Victor Ivan. WW once tested the limits of this editorial freedom by working his own editor into one of his tales of intrigue – and it wasn’t very kind on the editor either. But to Victor Ivan’s credit, the column survived.

WW’s weekly output is being noted and admired by a growing number of readers and media watchers. For example, the column earned him the merit award (Sinhala) for the Columnist of the Year 2009 at the Journalism Awards for Excellence held in June 2010. But acclaim is a double-edged reward that sometimes stifles creativity. Let’s hope that WW’s writing would retain its sharp, piercing edge for years to come.

I also hope that no one will attempt to translate this column into English. WW writes in his own unique Sinhala style that is idiom-rich and vividly expressive. The prose alternates between colloquial and erudite, occasionally touching on the bawdy yet on the whole staying within the limits of decency. The medium is a good part of WW’s message, and that will surely be lost in translation.

Having read WW’s satire column almost from the beginning, I can’t quite decide whether WW is extremely courageous, or completely foolhardy, to take on these topics and characters week after week. Just how do WW and his publisher get away with this level of undisguised, unadulterated lampooning? (Conspiracy theorists, please help!)

There is no argument, however, that Wimalanath Weeraratne’s satire fulfils a deeply felt need in contemporary Sri Lanka for the media to check the various concentrations of power — in political, military, corporate and religious domains.

I have never met WW in person, but he brings to life a phenomenon that I first outlined on my blog in July 2009: “There is another dimension to satirising the news in immature democracies as well as in outright autocracies where media freedoms are suppressed or denied. When open dissent is akin to signing your own death warrant, and investigative journalists risk their lives on a daily basis, satire and comedy becomes an important, creative — and often the only — way to comment on matters of public interest. It’s how public-spirited journalists and their courageous publishers get around the draconian laws, stifling regulations and trigger-happy goon squads.”

Science writer Nalaka Gunawardene has long been interested in the alchemy of humour as a political tool. He blogs on media, culture and society at http://movingimages.wordpress.com