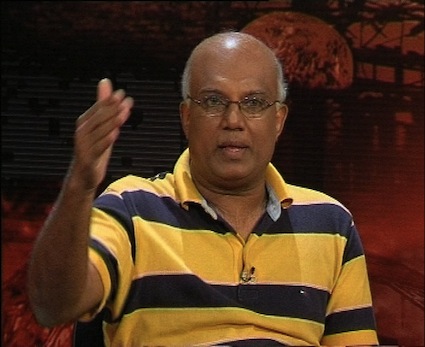

Piyal Parakrama on Sri Lanka 2048 TV show

Piyal Parakrama’s smile was regular and genuine, but it could be also be a bit misleading. Those who engaged him found that there was a keen mind, passionate heart and a sharp (yet always courteous) tongue behind that disarming smile. Opponents dismissed him lightly at their peril.

In public and media debates, Piyal could float like a butterfly and sting like a bee. That flutter and buzz are now abruptly silenced with his sudden death on March 3 at age 49. Another public spirited player has left the stage all too soon.

Piyal combined the roles of environmentalist, educator, researcher and media personality. He wasn’t part of the Colombo elite dabbling in a bit of green activism (mostly concerning wildlife or garbage) in their spare time. Instead, he straddled the parallel worlds of grassroots reality and the often ephemeral preoccupations of Colombo.

Not many knew him in formal capacities as the Executive Director of the Centre for Environmental and Nature Studies, or as founder president of the Nature Conservation Group, or as a consultant to various state and academic institutions. Some might remember his work at the now-defunct Sri Lanka Environment Congress (SLEC) that networked the country’s green groups. These various labels and ‘hats’ don’t really matter when assessing his overall contribution to the conservation movement. Piyal Parakrama was his own distinctive brand — admired, trusted or feared by different sections of society.

Piyal had emerged as a prominent member of what the late Ajith Samaranayake called Sri Lanka’s post-1956 generation: Sinhala-educated, with a high degree of political consciousness and deeply immersed in the art and culture of their times. How tragic, then, that Piyal should depart hastily – just like Ajith himself did, three years ago – when the children of 1956 are consolidating themselves in our politics, arts and commerce.

Given our common interests in development issues and the media, Piyal and I moved in partly overlapping circles. Our paths crossed frequently, and we shared public platforms, newspaper space and broadcast airtime. We even worked together for a few months in the late 1990s at the Sri Lanka Environmental Television Project. His communications skills were invaluable in rendering a number of international environmental films into Sinhala. More than a dozen years later, some are still in circulation.

We didn’t always agree. Sometimes we argued furiously over issues that we both cared deeply about but analysed differently. I felt he was too idealistic in his visions of reviving natural resource management practices of the past. Everyone is entitled to their bit of romanticism, for sure, but when advocating policy reforms or behaviour change, we need to root our positions on more realistic ground.

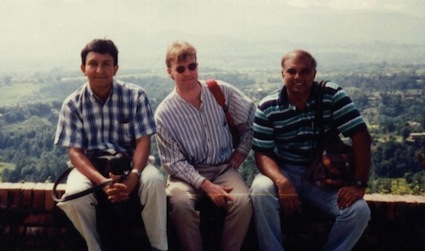

L to R – Nalaka Gunawardene, Mark Harvey (Internews) & Piyal Parakrama in Nepal, Oct 1996

Biodiversity

For example, Piyal passionately believed that Sri Lanka must go back to being an agriculture-dominated economy. (In 2008, agriculture’s contribution to the national GDP was a mere 12.1 per cent.) But unlike those who look back at 25 centuries of history in wistful nostalgia and try to revive times irretrievably lost, he rationalised his position. In a media interview given days after Sri Lanka’s long-drawn civil war ended, he explained his vision based on a ‘natural resource account’ for the country: “This is just like running a private company where it operates within the available resources, unlike the government which lives beyond its means.”

In that same interview, he underlined the need to develop agriculture in the North which was once very productive and grew a fifth of Sri Lanka’s food. He added: “We need to promote agro-eco tourism. We need to promote a tourism that will not ruin the environment and take away the little resources we have.”

Piyal’s forte was biodiversity – the collective term for all plants, animals (wild and domesticated) and their various habitats from forests and mountains to the coasts and oceans. His interest and knowledge were nurtured first at the Young Zoologists Association – where he remained a volunteer for 30 years – and later at the Lumumba Friendship University in Russia, where he studied biology from 1983 to 1986.

During the past three decades, Piyal and fellow activists have taken up the formidable challenges of conserving Sri Lanka’s biodiversity, long under multiple pressures such as growing human numbers, rising human aspirations, and gaps in law enforcement. Adding to the sense of urgency was the 1999 designation of Sri Lanka as one of the world’s biodiversity hotspots, where high levels of endemic species (found nowhere else in the wild) were threatened with extinction. Public and media attention is disproportionately focused on a few charismatic mega-fauna like elephants and leopards; in reality, dozens of other animal and plant species are being edged out.

In search of viable solutions for entrenched conservation problems, Piyal collaborated with scientists, educators, journalists and grassroots activists. Some industrialists and investors hated his guts, but he was much sought after by schools, universities and community groups across the country. Concerned researchers and government officials sometimes gave him sensitive information which he could make public in ways they couldn’t.

Some eco-protests grew into sustained campaigns. Among them were the call to save the Buona-Vista reef at Rumassala and struggles against large scale sugarcane plantations in Bibile. A current campaign focuses on the Iran-funded Uma Oya multipurpose project, which involves damming a river for irrigation and power generation purposes.

While environmentalists ultimately haven’t block development projects, their agitations helped increase environmental and public health safeguards. Occasionally, projects were moved to less damaging locations – as happened in mid 2008, when Sri Lanka’s second international airport was moved away from Weerawila, next to the Bundala National Park.

Political flirtations

The hard truth, however, is that our green activists have lost more struggles than they have won since the economy was liberalized in 1977. They have not been able to stand up to the all-powerful executive presidency, ruling the country since 1978 — most of that time under Emergency regulations. In that period, we have had ‘green’ and ‘blue’ parties in office, sometimes in coalitions with the ‘reds’. But their environmental record is, at best, patchy. In many cases, local or foreign investors — acting with the backing of local politicians and officials — have bulldozed their way on promises of more jobs and incomes. Environmentalists have sometimes been maligned as anti-development or anti-people. In contemporary Sri Lanka, that’s just one step away from being labeled anti-national or anti-government.

Piyal was astute enough to know the limits of knowledge-based advocacy and grassroots agitation in Sri Lanka. Maybe that’s why he also flirted with party politics. He was the founding president of the Green Party of Sri Lanka, a duly registered (even if little known) political party.

It was started to address systemic and structural reforms needed to place Sri Lanka on a more sustainable and equitable path of economic development. The founders wanted to promote concepts such as the ecological footprint and environmental justice. But in our tribal political culture, issue-based political advocacy can only go so far. I have no idea where the Green Party stands on key issues of the day, or whether it retains its original green character today.

While Piyal’s loyalty to the larger environmental or social causes was never in question, I sometimes wondered about the company he kept. A case in point was the Patriotic National Movement, a motley collection of Sinhala nationalists, west-bashers and conspiracy theorists. I’m not sure if that was due to simple pragmatism or deep conviction – we chose not to debate politics in our encounters.

One point where we had total agreement was on the power of mass media to inform and influence public opinion. He tapped every kind of mass media to reach as many people as possible in the shortest possible time. He was a regular contributor to newspapers and a popular guest on radio and TV talk shows.

He was also a trusted source of news and opinions for many journalists.

The last time we collaborated was in such a media venture. In mid 2008, Piyal joined an hour-long TV debate we produced as part of the Sri Lanka 2048 series. The show discussed the various choices and trade-offs that had to be made today to create a more sustainable Sri Lanka over the next 40 years. Piyal could speak authoritatively on several topics we covered in the 10-part series, but I invited him to the debate on managing freshwater. With his deep knowledge of traditional water and soil conservation systems, he was truly in his element there.

High and low shrill

I was always impressed (and even envious) of his command of Sinhala: his was a friendly style, informed and idiomatic without being excessively technocratic or legalistic. Piyal could deliver a coherent ‘sound bite’ to be used by a broadcast journalist, and also speak at length on the same topic. Not many activists or academics can manage this feat.

Another of his skills was what I call the variable shrill: ability to increase or tone down the amount of rhetoric to suit the occasion. Whenever he joined a public event or TV debate that I moderated, Piyal heeded my request for a low-shrill, high-substance contribution. (I’m all for plurality of views, but believe that rhetoric – like spices – is best taken in moderate quantities.)

Activism is not an easy path anywhere, anytime, and especially so in modern day Sri Lanka. All activists – whether working on democracy, governance, social justice or environment – are struggling to reorient themselves in the post-conflict, middle-income country they suddenly find themselves in. Their old rhetoric and strategies no longer seem to motivate the people or influence either the polity or policy. Many of them haven’t yet crossed the Other Digital Divide, and risk being left behind by the march of technology.

Don’t get me wrong. I salute every activist who comes forward to champion the public interest on behalf of a (mostly) passive and apathetic public. Most Lankans are either contented with the status quo, or just too preoccupied with their daily survival, to worry about the bigger picture. Activists work like the proverbial elves while the rest of us take it easy.

As indeed Piyal did, all his adult life, with few material rewards. He had no illusions about the hardships of his chosen career path. He also walked the talk, living frugally and treading very lightly on the earth. To his credit, he never abandoned the good struggle or sacrificed it all to become yet another presidential advisor…

Piyal heeded Anita Roddick’s advice to fellow activists worldwide: take it personally. Perhaps he took it too personally. Sitting next to Piyal’s silent body last week, his mother told me that he had no major worries or regrets in his life, and I want to believe her. But I also know there is little respite for those who care too deeply about the public commons and the common good.

We have been warned.

~

Science writer Nalaka Gunawardene dreams of becoming an activist one day, but for now, he remains a ‘critical cheer-leader’ of those who are more courageous. He blogs on media, society and development at http://movingimages.wordpress.com