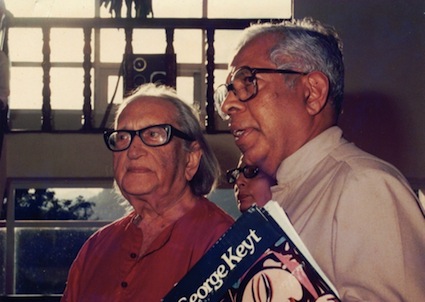

On 20 December 2009, we mark the 15th death anniversary of Professor Cyril Ponnamperuma, one of the best known scientists produced by Sri Lanka during the Twentieth Century.

He was both an internationally recognised researcher on the origins of life on Earth, and an early promoter of science and technology for development. His interests and involvements transcended his own discipline and homeland. He worked closely with the Pakistani Nobel laureate Dr Abdus Salam to promote science and infrastructural facilities in developing countries.

Dr Rajendra K Pachauri, director of The Energy and Resources Institute (TERI) in India (and now chair of the UN climate panel, IPCC), said upon Ponnamperuma death: “I don’t know of another single Third World scientist who has done so much for developing science and technology capacity in developing countries.”

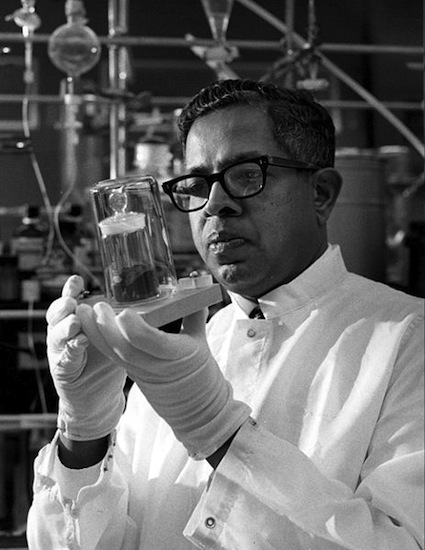

Born in Galle, Sri Lanka, in 1923, Cyril Andrew Ponnamperuma had his early education in Sri Lanka and India, and switched the chemistry after a first degree in philosophy. He obtained his bachelors in chemistry from the Birkbeck College of the University of London in 1959, and doctorate from the University of California at Berkeley in 1962.

He then spent nine years with the US National Aeronautical and Space Administration (NASA)’s Exobiology Division, where he became chief of its Chemical Evolution Branch. He was the space agency’s main investigator to analyse lunar rock and soil samples brought back by the Apollo astronauts. In 1971, he joined the University of Maryland at College Park, and where he later headed its laboratory of chemical evolution and remained an emeritus professor to the end.

If his research was probing our planetary past, his advocacy was firmly rooted in the real world of the present. He strongly believed that science and technology, when properly harnessed, could save lives, increase incomes and raise living standards across the developing world.

“Science and technology is the prime area in which the developing nations have to invest their resources to achieve economic development,” he argued. He often used an adaptation of Indian Nobel laureate C V Raman‘s words: “What the developing world needs is science, more science, and still more science.”

Problem solving

Ponnamperuma was lured back to the land of his birth by President Junius Jayewardene in 1984. He served as presidential science and technology advisor to Jayewardene and, for a while, to his successor Ranasinghe Premadasa. Concurrently, he served as director of the Institute of Fundamental Sciences (IFS) from 1984 to 1990, and was also founder director of the Arthur C Clarke Centre for Modern Technologies (ACCCMT) from 1984 to 1986. In these positions, he worked simultaneously on several fronts covering science policy, institutional building, fund raising, capacity building and public engagement.

Instead of tinkering on minor improvements or supporting research for its own sake, he wanted to mainstream science and technology for problem solving in sectors like agriculture, health, natural resource management and manufacturing industries.

“Our country made a major commitment to development by undertaking the Mahaweli (river) Project, even with borrowed money. Commitment to science is the Mahaweli of the future,” he told me in my first media interview with him in November 1986.

Ahead of that first encounter, I had heard Ponnamperuma’s detractors in the local scientific community describe him as aloof, impatient and even arrogant. Instead, I found him very courteous and engaging, the only discernible excesses being his boundless enthusiasm. Although he was an elder statesman of international science, he seemed more like a whiz kid – very bright, fully engaged in his pursuits and clearly enjoying them too.

He answered all my questions, including the critical ones, without turning defensive or dismissive. With patience and skill, he debunked the various myths and misconceptions about the IFS. He clarified that it wasn’t causing an ‘internal brain drain’; its research was supported entirely by external funds; and much emphasis was being placed on forging partnerships with local and foreign research institutes.

When the IFS was set up in 1981, it was partly modelled on the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research (TIFR) in India and the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel: it was meant to pursue basic research that could yield downstream benefits for solving development problems. As its second director, Ponnamperuma moved the IFS to a spacious complex in Hantana, Kandy, and set the fledgling institute ambitious goals.

As he told me: “With the help of our brilliant and talented local scientists…we hope to achieve in 10 years what took India 40 years. One great advantage for us is the lessons we can learn from the Indian experience.

‘Leap-frogging’ was a phrase he often used. He wanted Sri Lanka to adapt the latest scientific knowledge and technologies, bypassing those that other countries had tried and found to be messy or cumbersome.

Erudite, cultured and articulate, Ponnamperuma was a journalist’s dream: he could sum up complex issues in simple and engaging terms and metaphors — Â but these were more than mere soundbites. He was full of insights and anecdotes that humanised both science and its practitioners.

Over the next five years, I met and interviewed him many times, and found he always had something new, original and interesting to say. I don’t remember him ever being negative or pessimistic, even when things were clearly not going right. During the height of the Marxist JVP insurgency in 1988-89, when most public institutions were forced to close, the IFS quietly continued its work, with few tell-tale outward signs of activity. Ponnamperuma later compared this to London’s Windmill Theatre, which had performed shows underground right through the Blitz during the Second World War, and later claimed: “We never closed!”.

Meritocracy vs. Gerontocracy

Ponnamperuma’s passion for his research and institution building was palpable.

He aimed to create the right conditions for good science to thrive: decent salaries, access to latest knowledge, intellectual freedom, regular peer interactions and recognition. His recipe for nurturing world class science in a developing country: “Find the best young minds, give them all facilities, set them goals — and leave them alone!”

He did all this, and also buffered his researchers from the country’s formidable bureaucracy. As he explained, “A good scientist is like a Prima donna – he doesn’t want to be clamped down from nine to five.”

This approach, tried and tested in other parts of the world, met with cynicism from the very hierarchical scientific community and administrators in Sri Lanka. Apparently, their gerontocracy was threatened by Ponnamperuma’s meritocracy, so they quickly ganged up against him.

Ponnamperuma was aware of this hostility, which puzzled him because he had gone to great lengths to consult and involve everyone who mattered. For every senior scientist who saw value in what he was trying to do, there must have been at least three who wanted to have nothing to do with him.

One attribute that especially riled other mandarins of science was the presidential science advisor’s high priority for public understanding of science. Instead of building another ivory tower at the IFS, he reached out to schools, professional associations, the media and the local community in and around Kandy. The IFS held open days when anybody could walk in and ask questions. It also organised public lectures and symposia which were open to the media and interested non-scientists.

For him, public engagement was not an afterthought or token exercise in public relations, but an integral part of doing science. The only way to sustain the spirit and momentum of science, he said, was to make ordinary people understand and appreciate the processes of science. Since most scientific research and institutions were supported by public funds, the bill-paying public had every right to know what scientists were doing. Also, if voters didn’t care for science, elected governments were unlikely to take much interest in this endeavor either.

Alas, this high emphasis on public science was not widely shared by his local peers; I once heard them compare him to a ‘circus animal’ performing to the hoi polloi. Such sniggering reminds me of a New Yorker cartoon, which showed one crotchety-looking old man in a lab coat saying to another, “One thing I’ll say for us, Meyer—we never stooped to popularizing science!”

Through bickering and brickbats, Ponnamperuma continued his work with equanimity and resolve. He never complained, and instead looked for ways to improve the status quo. “What is the biggest room in the world?” he was fond of asking visitors and audiences. The answer illustrated his relentless quest for perfection: “Room for improvement!”

His biggest accomplishment — and lasting legacy — was not so much buildings, laboratories or institutions, but sparking off the interest in science among thousands of young people. That is much harder to achieve, and also impossible to quantify in Rupee or Dollar terms.

At IFS, he started an annual Schools Science Programme that enabled bright high school students to interact with top scientists at the institute and discover the rigours and excitement of science. He also guided and helped youth who wanted to pursue higher studies in science. Wasantha Samarawickrema, Ponnamperuma’s personal assistant at the IFS, estimates that more than 3,000 Lankan students went for higher studies at overseas universities largely on recommendations from this internationally respected scientist.

At ACCCMT, meanwhile, he launched the Science for Youth programme a two dozen of the brightest high school leavers were exposed to various (then) modern technologies over six consecutive weekends every year. As part of the 1986 batch, I can vouch for its inspirational value. Out of this programme emerged the Young Astronomers’ Association and Computer Society of Sri Lanka, the latter now a professional body.

Sleepless in Hantana

Ponnamperuma wanted young scientists to be versatile and resourceful. Doing peer-reviewed research alone was not enough; they also had to present their work to the public and media, and produce their own research funding proposals. Regular colloquia and publications ensured the IFS was a melting pot of ideas and people. Nothing was too far-fetched, and no member of the staff was too junior to speaker her mind. The divide of ‘two cultures’ was blurred by inviting top artists, musicians and other performers.

When the Japanese government granted US Dollars 5.2 million to equip the IFS labs in the late 1980s, they asked whether they could also give a personal present to Ponnamperuma. As Samarawickrema recalls, “He said: ‘Yes, I like presents, but can you please give us a Zen Garden for the whole institute?’”

So the Japanese contractors brought sand and pebbles from Japan and built an exquisite Zen Garden, which used to be one of Ponnamperuma’s favourite locations within the institute.

All this provided ample motivation while it lasted. A beaming Ponnamperuma recalled walking into a lab at the IFS close to midnight one day and finding a group of young researchers still at work. When queried why, one of them said, “Because bacteria don’t sleep at night!”

Close associates and staff sometimes wondered whether Ponnamperuma himself got much sleep, for he had an amazing capacity for work. At the time he was spending part of his time in Sri Lanka, he was already in his 60s but showed the stamina, focus and creativity of a younger person. For instance, he would land at Colombo airport after an inter-continental flight, make a three hour road trip to Kandy and still put in a full day’s work with little rest — and no sign of jetlag. His associates sometimes had a tough time keeping up.

Referring to his dividing time between two lands on opposite sides of the planet, he once said: “I now spend one third of my time in Sri Lanka, another third in the United States – and the balance in the air!”

Besides his substantive academic and leadership positions in these two countries, he also worked with the Third World Academy of Sciences (TWAS, now renamed the Academy of Sciences for the Developing World), CHEMRAWN (Chemical Research Applied to World Needs), and the Third World Foundation of North America, which sought to promote the use of science and technology for economic advancement in developing countries.

It can’t have been easy, in those days before email and Internet, to operate efficiently and seamlessly from multiple locations. Realising this, Ponnamperuma wanted to do something about it. Dr Rohan Samarajiva, now head of the independent think tank LIRNEasia, recalls being recruited to the IFS in late 1985. His brief, scribbled by Ponnamperuma on a post-it label, read simply: “Establish an uptodate science information system for the IFS.”

The idea was to link up with the ARPANET, the US government-funded research project in global computer communications that eventually grew into the Internet. “The IFS at that time had one luggable Kaypro computer, and no one in Sri Lanka had ‘always-on’ connections,” says Samarajiva. “But he was telling me to connect the IFS to the ARPANET!”

Inspirational maverick

Samarajiva came up with a cross-subsidy based solution that would allow commercial entities to use a leased line connecting to the ARPANET. But it didn’t take off for a variety of reasons; the first academic connectivity (LEARN) became a reality only in 1990, and unrestricted commercial Internet arrived in 1995.

This example illustrates how Ponnamperuma was a visionary, even if he was sometimes ahead of his time. Says Samarajiva: “He envisioned what was needed for this country…What he envisioned did come about. But would it have come about sooner and better if more Sri Lankan scientists and decision makers had put their energies into realizing his (or their) visions, and not into bringing him down?”

For sure, Ponnamperuma made his share of mistakes, one of which was expecting rapid change in a society that abhors it. Some of his ventures, such as the short-lived Winged Bean Research Institute, were based more on enthusiasm than on realistic assessments of need. His flamboyant style found little resonance in our largely dour scientific circles. On the whole, however, Ponnamperuma was a maverick whose potential Sri Lanka failed to harness.

He used to say, “Scientists are human, and they are biased as any other group. But they do have one great advantage in that science is a self-correcting process.”

Unfortunately, our politics and bureaucracy are not – so Cyril Ponnamperuma joined our land’s long (and depressing) list of might-have-beens.

Nearly two decades after Ponnamperuma’s premature exit from Sri Lanka, Samarajiva now wonders: “Was it that this is what visionaries do: inspire others to do new things and dream new dreams, and not actually implement their visions? The test, by that measure, would be who he inspired. I count myself as one.”

It would be instructive to find out how many others, now engaged in careers in research, industry, academia or government were similarly influenced and inspired by this colossus of public science. My guess is it would run into thousands.

And some of them are now ‘paying it forward’ with the same aplomb and zeal. While attending the recent international conference in Colombo to mark LIRNEasia’s fifth anniversary, I almost felt déjà vu, seeing Rohan Samarajiva in action.

Mediocrities everywhere beware: the Ponnamperuma contagion lives on.

###

After working in the print and broadcast media for years, science writer Nalaka Gunawardene has taken refuge online, where he blogs on media, technology and society at http://movingimages.wordpress.com