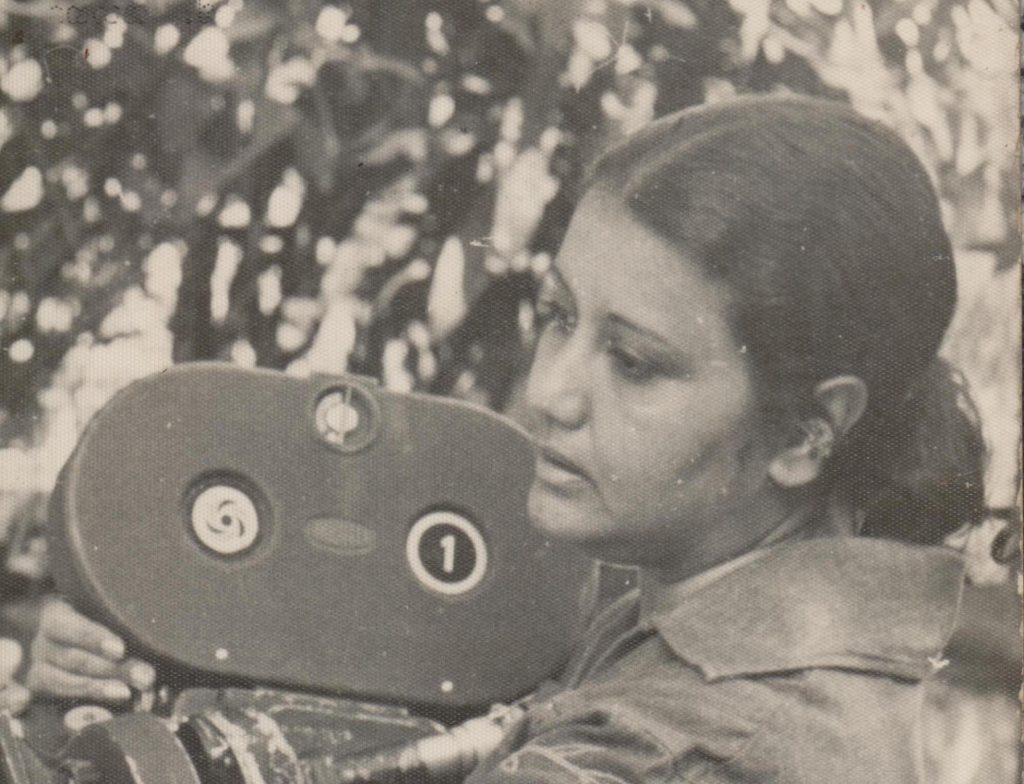

Photo courtesy of Uditha Devapriya

Sumitra Peries’s 90th birthday would have been on March 24. When she passed away in January 2023, she had not quite turned 88.

By that time she had reached and passed the peak of her career and was settling into a more relaxed and thoughtful life. She was meeting people at her residence in Mirihana, where she was forced to move to in 2018 after Lester Peries’s death, and she was being feted by the British, the Japanese, the Germans and the Indians. A British filmmaker had planned a retrospective of sorts for her films. The Germans had planned something similar for her. The Japanese felicitated her in 2019 with the Order of the Rising Sun.

There are times when I wonder whether Sri Lanka made use of her capabilities. Sumitra, like her husband and her contemporaries, was one of the preeminent intellectual icons of post-independence Sri Lanka. Their interests spanned and straddled diverse fields – not just cinema but also literature, dance, music and theatre. A week after Martin Wickramasinghe passed, Sarath Amunugama wrote a tribute in which he pointed out that the man was actually a contemporary of Piyadasa Sirisena, W. A. Silva and a host of other cultural figures from that period including Munidasa Cumaratunga.

To remember and celebrate Sumitra Peries, it is necessary to both place her alongside her intellectual contemporaries and distance her from them. This is because she was in many ways a product of her time but in many others an outlier of her times. Sumitra’s generation, we must remember, was also the generation of Mahagama Sekara, Gamini Fonseka, Madawala S. Rathnayake and Premasiri Khemadasa. That generation preceded the likes of Siri Gunasinghe, Gunadasa Amarasekara, Amaradeva and Chitrasena by a decade or so. The latter were actually Lester’s kinsmen and they, in turn, were a decade or so younger than the earlier generation of Wickramasinghe and Cumaratunga.

A number of scholars, the most recent being Shanti Jayewardene (whose brilliant, evocative study of Geoffrey Bawa surpasses all expectations), have charted the intellectual trajectory from British Ceylon to post-independence Ceylon to contemporary Sri Lanka. They examine the usual suspects from Sirisena to Wickramasinghe, Munidasa to Gunasinghe, Bawa to Peries and explore the similarities and differences. Shanti Jayewardene, in particular, takes pains to distinguish between Bawa’s and Gunadasa Amarasekara’s approach to modernity.

These are laudable intellectual exercises and they must be continued by other scholars, not least of all because we lack a definitive study of the intellectual strands that helped shape Sri Lanka. Yet even among existing studies, I find not a few names missing: there is, for instance, hardly any mention of Mahagama Sekara and if he is mentioned at all scholars focus on his literary and musical contributions, his poetry and his lyrics to the exclusion of his other aesthetic achievements including not just his paintings and sculptures but also his intellectual prowess.

Another name that has gone missing that is almost never invoked in such studies is Sumitra Peries. I fail to see why this is so. As I mentioned in one of my tributes to her, Sumitra was not merely an appendage of her husband’s work. The most definitive study ever authored about her by Vilasnee Tampoe-Hautin makes this point from the word go. Yet there is a tendency both to celebrate Sumitra for having contributed to her husband’s work (she edited his best films) and to see her through the lens of her husband. There is almost no acknowledgement of her contribution to Lester’s body of work, the role she played in indigenising her husband and grounding him in the land of his birth and the culture of its people. Instead, she is viewed as Lester’s wife rather than Sumitra Peries or for that matter Gunawardena.

Perhaps this is symptomatic of a larger malaise, a tendency in my view both to valorise wives of cultural figures for having enabled their husbands’ work and to bemoan them for not having gone beyond it. With other such female figures, and I need not mention names here because there are just so many, it is easy, even if deplorably so, to examine them purely through the lens of the men of their lives. Accordingly, while the man did his work, be it through writing, dancing, music, painting or sculpting, the woman managed the finances, ensured that her husband’s work survived his death and carried on his legacy by bringing up his children. With Sumitra, this frame is not easy to put on for two reasons: she was a filmmaker on her own right and she made a seminal contribution in terms of grounding her husband’s work in the ethos of her country.

Which is, I suppose, another way of saying that Sumitra possessed more agency, willpower and intellectual prowess than those other women who have been condemned to “live on and through their husbands.” The phrase is mine and I use it to illustrate just how tricky it is to view Sumitra through that same frame. While wives of cultural figures are celebrated for having sacrificed so much on the altar of their husbands’ work, Sumitra forged ahead with her own career while battling what she herself described to me as a male dominated field. The Sinhala cinema, for all its faults, has since allowed more women in yet we forget that even at its peak women were seen as no more than glamour girls, the sort who could only act in front of cameras and not supervise production behind them.

This is why I think she was both a product of her time and an outlier of her times. Sumitra did much in breaking the glass ceiling and I do not think we have been grateful enough to her about that. She continues to be side-lined from studies of Sri Lanka’s post-independence intellectual and cultural trajectory. The long list of our cultural figures, formidable as it is, is unabashedly and unashamedly androcentric. It is undeniable that Sumitra figured in among that crowd on the merits of her own work, not merely as a director but also an editor, an intellectual and aesthetic gadfly – a Sri Lankan woman of the world, as I described her in another tribute I wrote after her death. But just where is the acknowledgement of all these contributions? That, I am afraid, has yet to come out. It must.