Photo courtesy of PMD

Sri Lanka has a tradition of strong and independent civil society organisations and of professional (and organisational) autonomy within many branches of the state apparatus. By the turn of the century, it seemed increasingly obvious that this institutional basis for pluralism had been seriously eroded by politicians at every level. As evidence and illustration one could have cited: (a) constitutional changes that created a very powerful executive presidency (b) routine attempts to bring the entire extended state apparatus, including the police and judiciary, under the direct and complete control of the political executive (c) the routine flouting of the law by the politically connected (d) the frequent murders of journalists and lawyers whose activities were embarrassing to the government (e) official encouragement for rabid anti-Tamil and anti-Muslim sentiments and actions (f) the increasing size and influence of the armed forces as the country faced growing internal armed conflict from 1971 onwards and (g) the atrocities (and extortion activities) that were committed by these forces (and the unofficial armed groups that they employed) as they defeated the JVP in 1971 and 1987-9 and the various Tamil separatist groups from the early 1980s to 2009. Especially after Gotabaya Rajapaksa was elected to the presidency in 2019 and began to appoint ex-military cronies to senior government posts and to foment violence against Muslims, there was plausible talk of plans to institutionalise some kind of (Sinhalese Buddhist) militarised regime.

The wisdom of hindsight suggests that we perhaps focused too much the signs of deteriorating governance and not enough on the evidence of the persistence of pluralist institutions, attitudes and practices. A notable example of the latter was the successful resistance to the attempted Rajapaksa (non-military) coup in 2018. In 2015, what looked like an inevitable third presidential election win for Mahinda Rajapaksa had been thwarted by a skilfully executed plot on the part of non-Rajapaksa political elites. This split Rajapaksa’s party and narrowly elevated one of his more senior (non-family) ministers, Maithripala Sirisena, to the presidency. Sirisena then called parliamentary elections that resulted in a narrow majority for the plotters under the leadership of Ranil Wickremesinghe, who became prime minister. But Wickremesinghe showed scant respect for Sirisena and allowed him little power. In 2018, Mahinda Rajapaksa persuaded Sirisena to dismiss Wickremesinghe and appoint him, Rajapaksa, as prime minister. Parliament was opposed and Sirisena tried to prevent it from meeting. However, a large number of demonstrators camped out permanently in front of the prime minister’s house to protest; the speaker insisted on recalling parliament despite physical threats from some of Rajapaksa’s MPs; and the Supreme Court ruled against Sirisena. The coup collapsed.

Rohan Samarajiva gives us several more recent examples of this pluralist persistence. It extended well beyond the ranks of political and civil society activists. In late April 2022, at the height of the political stand-off between the aragalaya and the regime, some rather staid establishment organisations issued carefully worded statements that in effect backed the aragalaya. They included the Mahanayakes (heads) of the main Buddhist orders (Malwatte, Asgiriya, Ramanna and Amarapura); the Chamber of Commerce; and MAS holdings, the country’s largest employer and exporter. Within the state apparatus, the judiciary has generally retained its autonomy and the Commissioner of Elections even more so with the support of independent civil society election monitoring organisations like PAFFREL. Polling has generally been free and fair and has become increasingly free of violence that was common in the 1970s.

Part of the reason for the endurance of pluralist political institutions and attitudes is that attempts to institutionalise authoritarian governance practices and structures were to some degree performative and less consistent and coherent than they sometimes seemed. For example, since 1980 Sri Lankan and locally active international NGOs have been required to register with the government under the Voluntary Social Service Organisations (Registration and Supervision) Act No. 31 of 1980. Despite understandable and continuing concerns that this legislation will be used to exercise real political control over the NGO sector, that has not generally been the experience to date.

Similarly, efforts to give the military a more permanent role in governance seem more amateurish in retrospect than they did at the time. Again, Gotabaya Rajapaksa is the key figure. He was an ex-military man who had been Secretary of Defence between 2005 and 2015 when his brother Mahinda was president. After the end of the Tamil separatist conflict in 2009, the armed forces had remained excessively large and had been employed for a wide range of non-military purposes. On becoming president in 2019, Gotabaya Rajapaksa immediately appointed a number of ex-military officers to senior civilian government positions. But a military that is not institutionally coherent and disciplined cannot play a constructive role in national governance. Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s military appointees did not represent the army or the tri-forces in any collective or institutional sense. They were largely personal cronies of the president. And Gotabaya Rajapaksa himself was not a particularly unifying or respected figure within the armed forces. While Secretary to the Ministry of Defence, he had tried to appropriate for himself most of the credit for the military defeat of the LTTE. There had been a strong rival claimant: General Sarath Fonseka, Army Commander at the end of the war in 2009. Fonseka had then become the common opposition candidate for the presidency in 2010, standing against Mahinda Rajapaksa and by extension the Rajapaksa family more generally. After his defeat in that election, Fonseka was arrested in an outrageously humiliating way on false charges. Although no longer a serving officer, he was court marshalled and imprisoned.

In 2022, it was mostly the police and Rajapaksa thugs who meted out violence against the aragalaya. The military did not step in to defend Gotabaya Rajapaksa. To allay fears that they would be called in, on April 18, the Defence Secretary assured the armed forces that they would not be used against peaceful protestors. It seems that some senior military men were inclined to intervene. But that would have been very risky. The rank and file of the army in particular were dominantly young Sinhalese Buddhist men from rural areas. While their officers enjoyed many privileges, living and working conditions for the lower ranks were often very poor. Rates of desertion were – and are – high. It is widely believed that many soldiers would have refused orders to use violence against the aragalaya.

Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s efforts to bring the military into politics were not part of a coherent, long term project and were short lived. In the meantime, the Sri Lankan military, like its peers in India and Bangladesh, had tasted the pleasures of serving in UN peacekeeping missions overseas (Haiti, Lebanon, South Sudan and Mali) and learned that these opportunities were not available to forces that were conspicuously engaged in political repression at home.

Changes in occupational structures

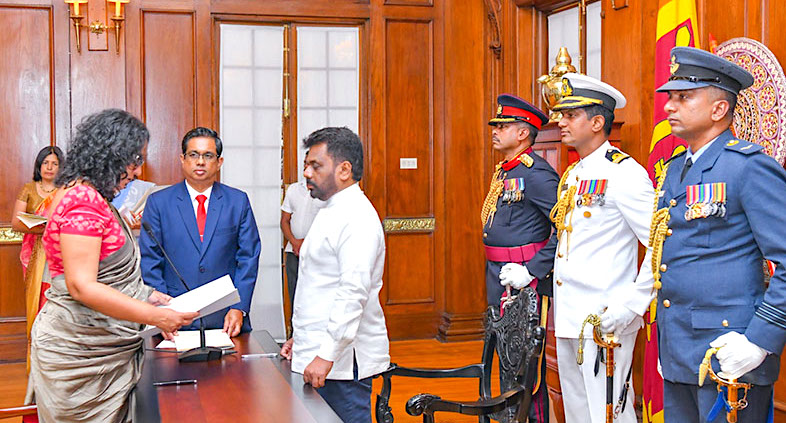

Like its predecessors, the new NPP cabinet is almost entirely male and Sinhalese. But it dresses differently. Of the 25 men in the official photograph of the 2020 cabinet, 13 wore national dress – the starched plain white sarong and kurta that has been close to the standard uniform for politicians since the middle of the last century. Otherwise traditionally worn by local dignitaries like school principals or ayurvedic practitioners, national dress references indigeneity and a claim to affinity with ordinary people. It originally contrasted to two other sets of formal attire worn by male members of the national elite: the Western suit and the elaborate traditional dress of those who held feudal titles within the colonial administrative system. Of the other 12 men in the 2020 cabinet, three wore Western suits with shirt and tie and nine compromised with a variant of white trousers and a white shirt or kurta. Compare the official photograph of the new 2024 cabinet: 13 of the 20 men wore suits with shirt and tie, six went for the compromise and only one wore national dress.

It would not be helpful to think of these sartorial differences as signifying anything about indigeneity or Westernisation. The prevalence of suits in the new cabinet reflects the extent to which the NPP has appropriated the trope of professionalism – a term that implicitly references formal education and qualifications and contrasts with the implied opportunism, self-seeking, unreliability and short termism of other politicians and parties. The new cabinet is certainly educated. Of its 22 members (including the president), 18 have at least first degree; five have doctorates; and seven have worked as academics. By contrast, only one has been a full time trades union organiser.

This esteem for professionalism is not new to Sri Lanka. The large and active Organisation of Professional Associations dates back to 1972. Neither is the NPP the first political party in recent years that has tried to own the term. Gotabaya Rajapaksa was elected to the presidency in 2019 while claiming not to be a politician and with the strong support of Viyathmaga, an organisation formed in 2016 that almost defines itself in terms of professions and professionalism and typically used Professionals for a Better Future as its motto. Viyathmaga had very little influence in Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s government, and quickly faded away. To some extent at least, we can understand its pre-election prominence as part of a strategy by Gotabaya Rajapaksa to gain some political leverage within the Rajapaksa family, particularly in relation to his brothers Mahinda and Basil who, in different ways, were much more accomplished politicians. Basil managed the family political party, the SLPP, whose ethos was virtually the polar opposite of professionalism. The SLPP won out over the Viyathmaga group.

Until a few years ago, Sri Lanka seemed stuck with a culture or style of electoral politics that dated back to the 1956 when S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike’s new Sri Lanka Freedom Party swept elections by adopting a pro Sinhala and a pro common man stance. Bandaranaike’s almost equally elite competitors quickly adopted that style. It was highly verbal and in many senses intimate and familiar. Politicians were expected to interact intensely with the people, understood principally as villagers and farmers, and on the political left, the working class. With echoes of Gandhi, the Indian National Congress and the narrative of politicians as servants of the people, they adopted national dress virtually as a uniform. The rural, agrarian Sri Lanka in which that political culture was born was always larger and more significant in the imagination than in reality. Today, agriculture provides very few livelihoods. The typical young villager is almost as likely to be serving in the army as ploughing a field. Agriculture accounts for less than 10 percent of GDP and the service sector for 60 percent. The noisy, personalised and directly interactive style of politics appeals less to people who work in offices, medical and care services, tourist hotels, IT, retail, the armed forces and food delivery in more or less urbanised environments. Government incompetence disrupts these kinds of economic activities more directly and visibly than small scale agriculture. Professionalism in governance, however exactly it is understood, resonates widely. The NPP was not the first political group to detect its electoral appeal. They were the first to fully internalise it. Among other things, they have largely avoided the sexist and vulgar language that other politicians sometimes use publicly. And that in turn helps explain why the NPP is the first political party to have more than a trivial proportion of female MPs.

NPP leadership and politics (the party)

We do not know how well the NPP will govern. Their successes in party building and in electioneering augur well. These are due in large part to the leadership of President Anura Kumara Dissanayake, a relative veteran of electoral politics with some brief previous ministerial experience in the 2004-5 coalition government, who has so far exhibited more electioneering skill and statesmanship than many people expected. The president and party have made a number of good calls over specific tactical issues. In particular:

- The party generally had a good aragalaya. They were visibly present but generally avoided asserting strong leadership in response to a widespread view that this was a people’s movement and politicians were not welcome if they were to try to take control. The NPP could keep a distance from the more militant and potentially violent cutting edge of the movement in part because other groups, notably the Frontline Socialist Party (FSP) were willing to place themselves there.

- The strong emphasis in the run up to the 2024 elections on the role of government corruption in triggering the 2022 economic crisis was clear, simple and electorally very powerful. It helped to keep attention off the thinness of the NPP’s own economic policy programme.

- It has made sense to delay as long as possible any discussion of the constitutional status of the Northern and Eastern Provinces and the broader question of devolution. These remain hot button issues. Any hint of a substantive government position risks losing more support than it gains, either from the politicians in the Northern Province to whom these issues are highly emotive and almost existential, and/or from those people in the South, including many NPP members and voters, who stick to the majoritarian rejection of almost any kind of devolution. The NPP did extremely well in the parliamentary elections in Jaffna district as a result of long term grassroots political activity focused on the material concerns of poorer people. The party seems to be experimenting with what has long been the orthodox Marxist position on Tamil dissent and separatism: that it is fundamentally rooted in class, inequality and material poverty and should be tackled as such rather than through constitutional and administrative reforms. It is worth a try, although probably not a position that can be held for long.

However, the big achievement of the NPP leadership goes well beyond smart political tactics. It has been the creation of the kind of a political party that Sri Lanka needs if it is to revert to being a stable democracy. It (a) has a real base membership of people who identify with and work for the party on a long term basis (b) has some degree of internal democracy and (c) is run by its cadres and the leaders they choose, rather than notables with ownership rights. With the partial exception of the Marxist parties in the mid 20th century, especially the LSSP, Sri Lanka has never been privileged to have such a party. Many smaller and short lived political parties have been the creations of individual notables. Larger and more enduring parties have been created by coalitions of notables. As mentioned above, those coalitions have become less and less stable in recent years, with the result that it has become even more difficult for voters to vote with any confidence for anything that resembles a policy programme.

To some extent, what has happened to political parties in Sri Lanka mirrors what has happened in democracies globally. Active membership of political parties has declined as political engagement moves online. Why then is the NPP different, and why might we be optimistic about it having a positive spread effect in the country? The answer to the first question seems to lie in the NPP’s particular hybrid history. Its origin lies in the JVP that has a long history of commitment to taking power through insurrection, conflict with and persecution by the state (the police, the armed forces and ruling parties), and building popular support for non-electoral reasons. The NPP was formed in 2019 jointly by the JVP and “21 diverse groups, including political parties, youth organizations, women’s groups, trade unions, and civil society organizations”. This alliance with other groups helped allay fears stemming from the JVP’s radical and sometimes violent history. It also provided a supply of accomplished and respected people from outside the JVP to stand for election nationally and take ministerial portfolios. The hybridity or duality of the NPP is embodied in the fact that there is not a high degree of overlap between cabinet membership and membership of the JVP politburo. This is an obvious source of potential conflict and indeed it would be amazing if conflicts do not emerge. But it is also potentially a source of great strength.

One of the great vulnerabilities of political parties in electoral democracies is that, because most or all of their leaders compete in elections and take government posts, they lose their organisational coherence and sense of mission and become driven by electoral politics and the spoils of office. A political party that aims to promote substantial reform in an electoral democracy needs to retain an organisational base that is to some degree separate and focused on long term policy issues. That is one reason why BJP governments in India have been so relatively effective at winning elections and using power to further Hindutva goals. Beneath and intertwined with the BJP lies the RSS and a wide range of other Hindutva socio-political organisations. Their roles include supporting the BJP and keeping it honest, as they see it. Similarly, we can expect conflicts as the JVP tries to keep the NPP government honest. We should be worried if they become too intense but equally worried it they do not emerge at all.

Prior to the 2024 parliamentary elections, non-NPP politicians were intensely engaged in the coalition bargaining game: negotiating about alliances, defecting from one group to another and spreading rumours about who might ally or defect from where to where. The NPP was criticised for what seemed like an arrogant refusal to consider alliances or to take in any defectors. But that refusal reflected more than a calculation that the party could win alone. It was central to the credibility of an organisation that (a) presents itself a completely new political force untainted by the corruption of the old politics (b) motivates its own cadres by offering them the prospect of standing for election in return for their commitment and efforts and (c) provides voters with some assurance that they will get what they vote for at least in terms of policy stances if not policy details. That is a very different kind of party and a different kind of electoral politics than Sri Lankans have previously known. The NPP will not be able to fully maintain its wholesomeness as it grapples with the challenges of governing. But if it can retain much of it and also motivate the main opposition party to move in the same direction, then it will change the way in which the country is governed quite positively.