Photo courtesy of BBC

Naming the names of the dead is an important act of memorialisation; for those they leave behind, it is their names that contain their essence.

Palestinians in Gaza are writing the names of murdered family members on the ruins of their homes to mark their graves under the rubble because Israeli bombardment prevents the recovery of all the victims.

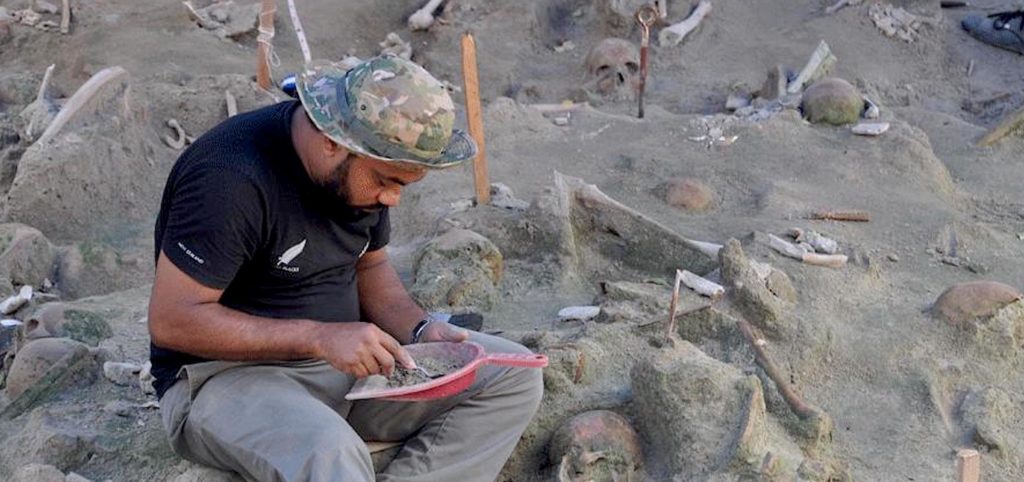

The thousands of dead and disappeared in Sri Lanka all had names. Some have been forgotten or are unknown while others live on through their families who are still waiting for answers as to their whereabouts. The continuing discoveries of mass graves dotted around the country can provide clues as to the names of the slain, through forensic investigation of remains.

The Naming of Names is a book of poetry by poet and translator of Tamil poetry into English, Shash Trevett. “This book is filled with names. They will be strange and unfamiliar to you. As you turn these pages you will be tempted to gloss over, skim, even ignore them. Please don’t. There is music in these names.

“Each is a whisper of a life lived and loved. Each a Tamil man, woman or child killed by the state. Each a forgotten victim, mere collateral damage, peripheral, expendable.

“These names are mausoleums for those denied gravestones. They are the staccatoed prayers of remembrance. The hiss of incense on a funeral pyre,” she writes in the introduction to the book.

The book is based on the work carried out by the North East Secretariat on Human Rights (NESHR), which catalogued each massacre of civilians during the civil war, producing a description, a map and eye witness accounts where existing. Each report ended with a list of names of those killed. Sometimes there were only a few names, sometimes there were hundreds. Sometimes, where entire villages had been wiped out, no names were recorded.

Shash answered questions from Groundviews on why she wrote the poems, the importance of remembrance and what impact she hopes the book will achieve.

Can you give some background about yourself?

I was born and grew up in Manipay, Jaffna Province. My father was a surgeon at Manipay Hospital and my mother was part Indian Tamil and part Dutch Burgher although she identified fully as Indian. We had to leave Sri Lanka in 1983 as my father was targeted by both the LTTE and the Army: we claimed refuge in Tamil Nadu and lived there for four years. When the Peace Accord was signed with India in 1987, my mother and I returned to Jaffna, reclaimed our house in Uduvil from the LTTE and looked forward to picking up our lives again. Unfortunately, as we all know, the peace didn’t last. The Indian Army, working on faulty intelligence, targeted us and our house mercilessly, thinking that it was still a LTTE compound. Despite my mother speaking to the Indian forces in Hindi and explaining that we were just a house of women, we were constantly in their crosshairs. The situation escalated from the odd mortar being fired at our house, to neighbours being killed, to our house being bombed specifically, to us being lined up to be shot, the assaults on our minds and bodies became so horrific, we eventually escaped (a nightmare journey) and claimed asylum in the UK. I finished my schooling in the UK and went to university to read English Literature – I had always wanted to be a writer – and here I am now writing poems about a past I cannot put behind me.

What motivated to you to write these poems?

My poetry engages with the trauma borne by civilians who are subjugated by the inhumanity of war. In 2021 a conjunction of events led to me think about the names of civilians killed in warfare: what happens to the names that are left behind once the person who once wore them is killed. I’d read and had been inspired by the 2020 collection by Belarusian poet Valzhyna Mort (Music for the Dead and Resurrected, 2020) and attended her Poetry Society Annual Lecture in March 2021. In it she read the names of the occupants of one of the Belarusian villages fire bombed in the Second World War with a complete loss of life. It was so moving listening to her intoning the names of the dead, accompanied by their ages, and although we weren’t told anything about them, one could picture generations of families living and dying together. I had just finished writing my pamphlet (From a Borrowed Land, 2021) and although in the middle of editing Out of Sri Lanka (2023) I was gathering material for my next poetry collection. I had come across the names and photographs with dates and places of birth of the schoolgirls murdered in the Sencholai massacre of 2006. Going through the memorialisation of their names, each name a story left unfinished, I had begun writing about these schoolgirls when I listened to Mort’s Poetry Society lecture. I realised that it is enough to merely name the names: we do not need to know how these victims lived or how they died. It is enough to know that they once were and that they had been killed. That they had not been given the chance to complete their stories, to fulfil all the promise they held within them. From there I started collecting the names of the Tamil dead – civilians only, never combatants – and the collection started taking shape.

What is the significance of the names?

On a macrolevel, these names are significant because they are pegs on which we hang the pages of our nation’s history. On a microlevel these names matter because they once clothed a breathing, dreaming, thinking human; someone precious to someone else. It is so easy to dismiss civilian deaths as unfortunate or as collateral damage. We are all tired of politicians and commentators dismissing the massive loss of life in Gaza as being either “a necessary consequence of fighting terrorism” or as a regrettable outcome of “seeking peace”. These are words of distraction, an evil technique which destroys the humanity of both those who speak them and those who are taken in by them. No, names are not a sterile collection of phonemes and graphemes. Naming a name slowly, deliberately, paints pictures in our minds. Taking a couple of names randomly from the book, the name Sarojadevi makes us think of old films, of music, of silk saris shot with gold. Maybe the parents of this Sarojadevi were a fan of the actress? Maybe one of her songs was precious to them. Maybe they pictured their daughter living a similar enchanted life. Or the name Krishdyan, a Tamilisation of Christian – an amalgam of Tamil and English, Hindu and Christian – tells us something about the background of this person. Did he mind wearing his religion as his name? It is not surprising that recently there have been videos of people reading lists of the names of the dead children of Gaza, of people counting how long it would take to name all the dead of this inhumane war. Naming names holds in prominence the human, the person; it is impossible to picture merely a number when faced with the music borne by a name.

Why is it important to document the events?

We are increasingly living in a dystopian, post-truth world where the concept of alternative fact instead of being laughed at, is being used to justify lies and inhumanity. We live in a time where the government refuses to allow a dissection of the events that led to the end of the civil war in 2009. Politicians are too keen to move on, to paper over the unpleasantness and dismiss accountability. At such times these names are a necessary corrective; by naming them we claim that their deaths weren’t in vain. I hope my book will be an archive that states that these civilians mattered and that they matter still.

The poems are very powerful and descriptive. How were you able to get such detail?

I think poets hope their words will take readers on a journey within words themselves. That readers will appreciate the significance and weight of words used in a specific way as to paint a picture we can all peek at. I am greatly indebted to the work carried out by the North East Secretariat on Human Rights (NESHR), who catalogued each massacre of the civilian population during the civil war. Each of their reports ended with a list of names of those killed. Sometimes there were only a few names, sometimes there were hundreds. Without their methodical cataloguing of the names of the dead, often in dangerous conditions, I would not have been able to write this book. I have only been able to use a small sample of all the names I collected. These in turn are but a small sample of all the names that were lost over 26 years.

What impact do you hope the poems will have?

I have no idea what impact my book will have, if any. Once you publish a book, it is up to the reader to make of it what they will. You can only hope that you have done enough to maybe make the reader think. Having said that, I wish that readers will appreciate the enormity of the loss faced by populations who endure subjugation. That casualty numbers in newspapers are someone else’s mother, father, son or wife. Everyone knows this, on an intellectual level, but I hope these poems will make people feel this. I also hope that readers will understand that war trauma, grief or loss doesn’t ever end. It is pernicious – it invades the core of those who survive; these are scars they will carry for ever. I think, especially, of the Tamil mothers of the disappeared who, every day since the war ended, hold in protest placards with the names and photos of the children they have lost. Please don’t ask them to move on or to stop remembering their dead. It is as if you ask them to stop breathing.

How did writing the poems change you as a person?

I had spent months reading accounts of massacres and killings; the noting down of names was a distancing device. It allowed me to shut off the part of myself which would have become overcome by the magnitude of the loss faced by the Tamil community in Sri Lanka. But when it came to weaving poems from these names, I could not shut off the part of me that feels. Writing these poems was hard, emotionally and mentally, and my own war trauma resurfaced in a very debilitating way. I’d finished writing the first draft of the book by October 2023 just as the current conflict in Gaza began. As I held close my Tamil dead while the Palestinians mourned their current dead, the impotence I felt cataloguing the names was compounded by the impotence I felt as I watched my government in the UK and other governments across the world turn a blind eye to the will of their people. Every weekend thousands of people march in the UK demanding that our government calls for a ceasefire in Gaza. Their protests fall on deaf ears: cold, callous, deaf ears. The war in Gaza, which so closely mirrors the events in Sri Lanka, was a bloody backdrop to this book, which is itself saturated in blood. I am still trying to find a sense of equilibrium but I suspect it will take some time for me to wash away the taste of both bitter disappointment in world leaders (yet again) and impotent rage.