Photo courtesy of Reddit

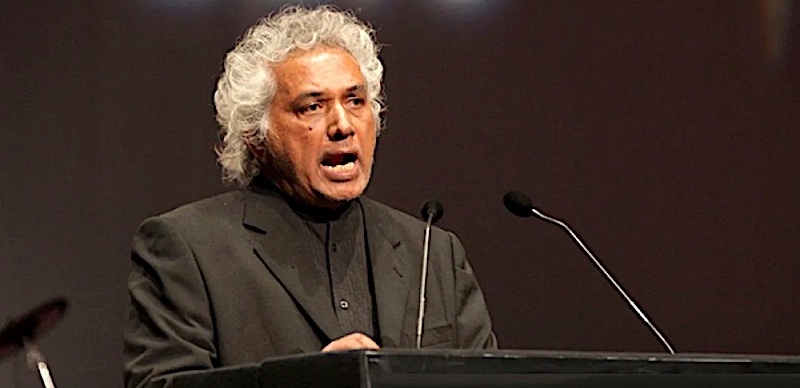

Comrade Dr. Vickramabahu Karunaratne’s legacy deserves recognition through thoughtful analysis.

Comrade Karunaratne’s political journey began within the Lanka Sam Samaja Party (LSSP). However, in 1972, he parted ways with the LSSP when it joined forces with the Sri Lanka Freedom Party (SLFP). The 1972 republican constitution drafted by the SLFP inadvertently transformed Sri Lanka into a Sinhala Buddhist state, marginalising the Tamil community. Subsequently, the 1978 Constitution, enacted during Prime Minister J.R. Jayewardene’s regime (with current president Ranil Wickremesinghe as a cabinet minister), further entrenched Sinhala separatism, further alienating Tamil speakers.

Comrade Karunaratne’s principled stance against the 1978 constitution led to his dismissal from the academic position he held at the University of Peradeniya’s Faculty of Engineering. His commitment to addressing the national question, rooted in fairness, justice, and recognition of rights, exposed him to death threats. In 1988, the Deshapremi Janatha Vyaparaya (DJV) targeted him for advocating on behalf of Tamil people subjected to state terror.

Despite political shifts later in life, Comrade Karunaratne consistently championed national unity based on equality, autonomy and self-determination. Even posthumously he faces criticism from fervent nationalists. As we reflect, let us recognise the consequences of short-sighted policies adopted by our political leaders throughout post-independence history.

In 1956, when Prime Minister S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike pledged to make Sinhala the official language of Ceylon, he included a proviso: Tamil would have administrative status. As a 12 year old, I listened to Mr. K.M.P. Rajaratne, a fervent Sinhala nationalist, on Radio Ceylon advocating for extreme measures like skinning Tamils to make shoes. Meanwhile, Tamil politicians, although I had not heard their live speeches, reportedly made similar statements about the Sinhalese.

The torch of Sinhala nationalism ignited by Mr. Bandaranaike and the SLFP, led to the enactment of the Sinhala Only Bill in 1956. Both the SLFP and the United National Party (UNP) supported this legislation, while the Lanka Sam Samaja Party (LSSP), the Communist Party of Ceylon (CPC, later the Communist Party of Sri Lanka), the Illankai Tamil Arasu Kachchi and the All-Ceylon Tamil Congress opposed it. The repercussions of this decision continue to shape Sri Lanka’s political landscape even after 68 years.

It is important to remember that a Sinhala Maha Vidyalaya operated in Jaffna during colonial times. Some Tamils learned Sinhala and respected Sinhalese traditions. However, the LTTE disrupted this trend, preventing the school’s operation after security forces set the Jaffna Public Library ablaze in May 1981. The subsequent anti-Tamil pogrom in July 1983, orchestrated by the UNP regime under President J.R. Jayewardene, exacerbated tensions.

The 1978 Constitution reinforced the supremacist provisions of the 1972 constitution adopted during the Bandaranaike regime. The Sinhala Only policy, established by the Official Language Act (No. 33 of 1956), further divided our once-unified, pluralistic society. Each constitution deepened the alienation of non-majoritarian communities. This process began in 1948 when the D.S. Senanayake regime disenfranchised Malaiyaha workers and escalated with state violence against Tamil youth.

Interestingly, students who attended colleges in Jaffna excelled in education without discrimination. For instance, Mr. K.B. Ratnayake, a Sinhala student at Hartley College, captained the cricket team and later became the speaker of parliament. Similarly, Mr. Maithripala Senanayake, who studied at St. John’s College, Jaffna, held several cabinet portfolios and served as acting prime minister.

The Sinhala Only policy had significant consequences for public servants. In areas where Tamil speaking populations were prevalent, Sinhala public servants were not required to learn Tamil. However, Tamil public servants – even those working in Tamil-majority regions – were compelled to learn Sinhala. As a result, the number of Tamil public servants in the state sector declined sharply.

Statistics reveal the impact: In 1956, Tamils constituted 30% of the Civil Service, 50% of the clerical service, 60% of engineers and doctors and 40% of the armed forces. By 1970, these numbers had plummeted to 5% of the Civil Service, 5% of the clerical service, 10% of engineers and doctors and a mere 1% of the armed forces.

In the 1960s, the government failed to provide documents or application forms in Tamil for the native Tamil speaking population. Protests by Tamil communities eventually led to a slight relaxation of language policies. The Indo-Sri Lanka Accord of 1987 recognised Tamil as an official language while Sinhala remained the country’s official language. Despite the 13th Amendment, which aimed to address these language disparities, full implementation remains elusive.

Consider the challenges faced by Sinhala speaking security forces personnel posted in Tamil majority areas. Their lack of competent Tamil language skills hinders effective communication with both the government and the local population. I raised this issue with President Chandrika Kumaratunga and Prime Minister Ranil Wickremasinghe during their tenures.

Had the JVP policy declaration from 1972 been consistently followed, the Indo-Sri Lanka Accord might have recognised both Sinhala and Tamil as national languages. The JVP also advocated for English as a national language although it ultimately it became the link language. Devolution of land, police and financial powers to provinces remains a contentious issue with the incomplete implementation of the 13th Amendment allowing external interventions, notably from India.

Recognising the short-sightedness of past Sinhala nationalists is crucial. The Sinhala Only policy did not benefit Sinhalese, Tamils or Muslims. Fortunately, recent shifts, possibly influenced by multicultural exposure, have eased some language restrictions.

I must mention Australia’s language policy. While lacking coherent principles initially, a National Policy on Languages emerged in 1987. It emphasised English proficiency for all, support for Indigenous languages (including bilingual education) and recognition of languages other than English.

Australia’s ground breaking multilingual policy, endorsed by both sides of the political spectrum, aimed at cultural enrichment, social justice, vocational opportunities and global trade promotion. As the world’s first comprehensive multilingual policy, it has become an influential landmark internationally. Over time, Australia’s increasing cultural diversity has made multilingualism an integral part of its social fabric, driven in part by economic imperatives to engage with Asia and diversify exports.

Notably, this policy explicitly outlines values to guide language decisions – a departure from the past. In Australia, English remains dominant, spoken by 72% of the population. Mandarin (3%), Arabic (about 1.5%) and Vietnamese (about 1.3%) reflect the country’s multicultural tapestry. Importantly, an employee’s pay cannot be influenced by their language or origin.

Visitors to Australian cities encounter a vibrant linguistic landscape: English, Mandarin, Arabic, Cantonese, Hindi, Italian, Greek, and more. In Central Australia, Indigenous languages such as Warlpiri, Arrernte and Pitjantjatjara thrive.

Contrastingly, in Sri Lanka – except for Colombo – the prevalence of Sinhala and Tamil speakers remains uncertain. Drawing lessons from Australia’s inclusive language policy, Sri Lanka can foster peace, human rights and social cohesion through equitable language education.