Photo courtesy of Bloomberg

In 2021 Ajay Lalwani, a local news correspondent for an Urdu language newspaper, was sitting in a barber shop in Sukkur, Pakistan. Some gunmen drove by and opened fire, striking Lalwani in the stomach, arm and knee. He died in hospital. Ajay was a Hindu journalist known for exposing the misdeeds of influential local leaders. Naresh Kumar, a witness in the case, subsequently died in a road accident considered suspicious and linked to the accused in Ajay’s murder.

In Sri Lanka, where the minority Tamil speaking community resides in the North and East, numerous journalists have fallen victim to murder or disappearance. The Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ), an organisation advocating for journalists, reported that 25 journalists lost their lives during the civil war, particularly between 1992 and 2022.

In India, authorities are increasingly targeting journalists and online critics for their criticism of government policies and practices including prosecuting them under counterterrorism and sedition laws, coupled with a broader crackdown on dissent; no group is more vulnerable than Muslim journalists. The number of journalists charged under draconian laws or different sections is an indication of the perilous state of free speech in India. The persecution of journalists grew by more than four times in the Narendra Modi years. According to data collected by the CPJ, 36 journalists were imprisoned in India between 2014 and 2023.

The latest Press Freedom Index revealed concerning trends for South Asian countries including India, Sri Lanka and Pakistan, indicating a significant decline in press freedom levels. Sri Lanka saw a steep drop from its previous position of 135 in last year’s Reporters Without Borders (RFS) report to 150 within just one year. India’s rank stands at 159 out of 180 countries in the Press Freedom Index, highlighting ongoing challenges in the media landscape. Pakistan follows closely behind at number 152.

These rankings shed light on the obstacles faced by journalists in the region who encounter a myriad of difficulties including threats, censorship, legal hurdles and physical as well as mental challenges. Some journalists have lost their lives while carrying out their professional duties.

These challenges are not limited to any specific group of journalists but are pervasive across the profession. However, journalists belonging to minority groups face additional hurdles and are particularly vulnerable to heightened risks and difficulties.

Labelled as terrorists

“There are two cases against me, one being the Unlawful Activities Prevention Act (UAPA) and the other is the Prevention of Money Laundering Act (PMLA) case. I have a charge sheet of 5,000 pages and it’s been almost 3 to 4 years that I haven’t even received my charge sheet. There are only allegations against me and no evidence has been found. Still, my job, health, finance and everything else suffers,” said Siddique Kappan, a journalist from Kerala who was arrested in October 2020 and was released on bail in February 2023 after more than two years following his arrest.

Kumanan, a journalist from the Mullaitivu district says, “For a prolonged period, we’ve been unjustly labelled as terrorists. Whenever we report for the rights of the Tamil people, we’re unfairly branded as such. Consequently, many journalists have suffered tragic fates including murder, abduction and forced disappearance. Even today such perceptions persist about us. We continue to be categorised within the general stereotype of terrorists, seen as undesirable elements by the state, perceived as accomplices and even as instigators of terrorist activities. We are called for investigation under the Prevention of Terrorism Act (PTA), which has become a new normal,” he said.

Journalist Meer Faisal revealed how the Tripura Police booked 102 social media handles for allegedly posting content to disturb communal harmony under the UAPA. “Many of us were booked for raising critical questions over institutionalised planned violence and there was no fact check on which report I was booked. It was just because we were highlighting the matter at that time,” said Faisal.

The UAPA is used against journalists who seek to investigate and report on a range of issues, trying to criminalise their legitimate work and stigmatise them as terrorists as well as having a chilling effect on the professional at large.False cases to silence dissent

Shams Tabrez Qasmi, the editor of the multilingual digital media platform Millat Times, has been booked for tweeting videos of the communal clashes in Kanpur in 2022 and no written notice has been sent to him yet. He also mentioned his colleagues who have suffered harassment and abuse because of their Muslim identity.

The fact checking Indian website Alt News’s co-founder Mohammad Zubair was arrested by the Delhi police in June 2023. The police alleged that a 2018 tweet by the fact checker “hurt religious sentiments”. In July, fresh charges of criminal conspiracy, destruction of evidence and foreign funding were added to the case.

Zubair said, “A Muslim man asking for accountability and working as a journalist is not a crime. I have to tell my younger colleagues that their work matters and bearing witness to horrors that would otherwise be forgotten is not a crime.”

Religious fundamentalism vs journalism

Durainayagam Sanjeevan, a journalist from Trincomalee district, explained, “When we cover religious matters, we confront threats from religious fundamentalists. Buddhist monks often clash with us and resort to violence, particularly when we report on unlawful encroachment in the name of Buddhism. They exert influence over our reporting, dictating what should and shouldn’t be covered. When we resist this control and report we face police investigations and threats, accusing us of causing racial tensions.”

In the northern and eastern parts of the country where Hindu temples are located, land belonging to Tamils is grabbed in the name of archaeology and Buddhist temples are constructed afterwards. There are also incidents where the majority forcefully takes over the land of minority people.

“Buddhistisation is currently underway in the North and East. It is an act of deliberate demographic change. Buddhist temples are built in Tamil areas. With the support of government departments such as the Forest Resources Department, Archaeology Department, Army and Police, the Buddhist priest acts as a strongman and carries out all the activities there. When we report such issues, we are often depicted as instigating religious tension with accusations that we are challenging the rights of Sinhala Buddhists to practice their faith,” said journalist K. Kumanan says.

“We have been arrested, assaulted, threatened, photographed and threatened. I was threatened with arrest when I went to report on the protest in 2022 and in 2019 when I went to report on the Buddhist conversion at Neeraviyyadi Pilliyar Temple, the police officer attacked me and knocked down my camera. Such threats have happened to all minority journalists like me in the North and East,” he said.

Online censorship

Shams Tabrez Qasmi said that Facebook deleted the official page of Millat Times in September 2021 without giving any notice or reason. The page had more than one million followers. Millat Times’ YouTube channel was put on a 90 day ban after the outlet published a news video on protests in Maharashtra against the COVID-19 lockdown.

In a democracy, journalists are being silenced due to their reportage and commentary on important issues and the democratic rights of citizens. The Modi government’s legislation to regulate the internet has not been received well by India’s digital media. The Information Technology (Intermediary Guidelines and Digital Media Ethics Code) Rules 2021 opens up digital media to discretionary powers of the government, including censorship.

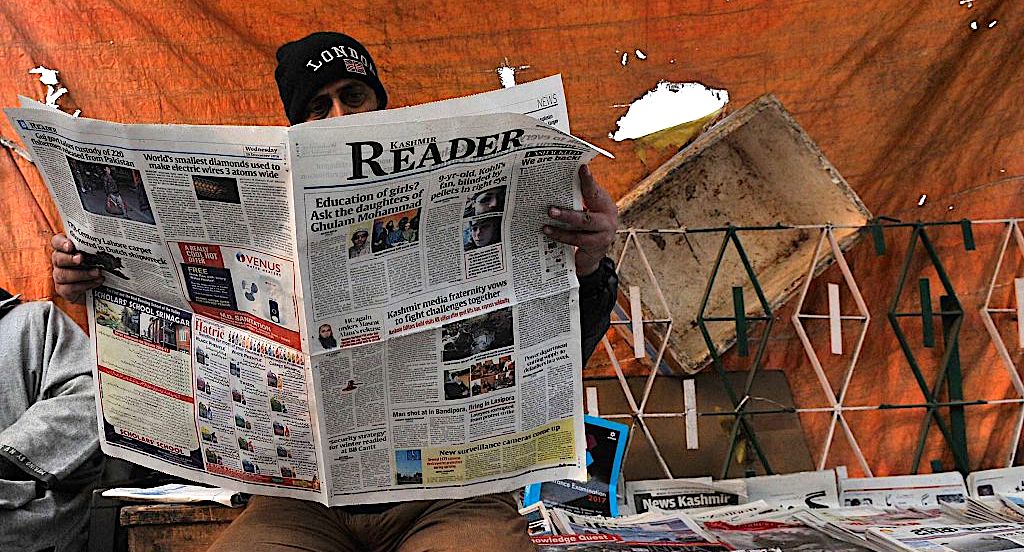

Due to the government’s tight control on the media in Kashmir, the situation of journalists in the predominantly Muslim region has sharply declined since the government in August 2019 repealed Article 370 and 35a of the Indian Constitution, which gave Jammu and Kashmir significant autonomy.

In Manipur in northeast India, which was reeling under a violent ethnic conflict from May 2023, the internet was shut down for seven months and continues to be patchy in designated areas. Purportedly a measure to curb disinformation and the circulation of inflammatory videos and messages on social media, particularly WhatsApp, it has also effectively prevented journalists from verifying information and publishing credible news.

The Modi years have been marked by government surveillance and the use of spyware against journalists, spiked stories, income tax surveys on newsrooms and intimidating morning raids at the homes of young journalists. Independent news outlets are being criminalised for critical reporting and journalists and their organisation are hounded by the authorities for doing their job.

Journalists have been criminalised

If you speak out for justice, a troll army will target you regardless of your name. However, if you have a Muslim name, the first thing you are advised to do is to go to Pakistan, said Ziya Us Salam, a senior journalist.

“There has been a concerted attempt at the marginalisation of minorities in general and Muslims in particular. Before 2019, there were lynchings of Muslims who were allegedly involved in cow slaughter or the transportation of cattle for possible slaughter. But post 2019, Muslims are being attacked simply for being Muslim. Minorities are the direct victims of Hindutva politics,” he said.

An independent Indian journalist Zakir Ali Tyagi said, “For Muslim journalists, writing has now become like walking on a double edged sword. If we want to write, we have to walk a difficult road. That is why some journalists have changed their field while there has also been an increase in the numbers of people choosing journalism as their professional field.”

Senior Pakistani journalist Gangu Mal has decided to leave journalism due to unsafe conditions, especially for religious minorities like himself. Gangu was attacked by two unidentified gunmen in November, 2023 and was injured. The motive behind the attack was to disclose the presence of Afghan refugees illegally.

Journalists in Pakistan face insecurity and various threats but the situation is even worse for those belonging to religious minorities. Approximately 130 journalists in Pakistan are rendering their services from religious minorities and they are particularly vulnerable compared to their counterparts from the majority religious community.

What should be done?

The CPJ’s India representative Kunal Majumder said that it was important for the journalist fraternity to start focusing on their issues and their safety because India did not have a culture of safety for journalists. There is no conversation about how you keep your journalist safe.

Recently CPJ’s Emergencies Response Team (ERT) compiled a safety guide for journalists covering India’s election. The guide contains information for editors, reporters and photojournalists on how to prepare for the election and how to mitigate digital, physical and psychological risks.

“The fraternity itself has to take the responsibility of care towards their reporters and they have to be mindful of them and they have to implement a lot of preventive measures, which unfortunately at this point is completely missing out of Indian newsrooms. But once you start putting these preventive mechanisms in place, the number of journalists being protected will definitely go up,” said Majumdar.