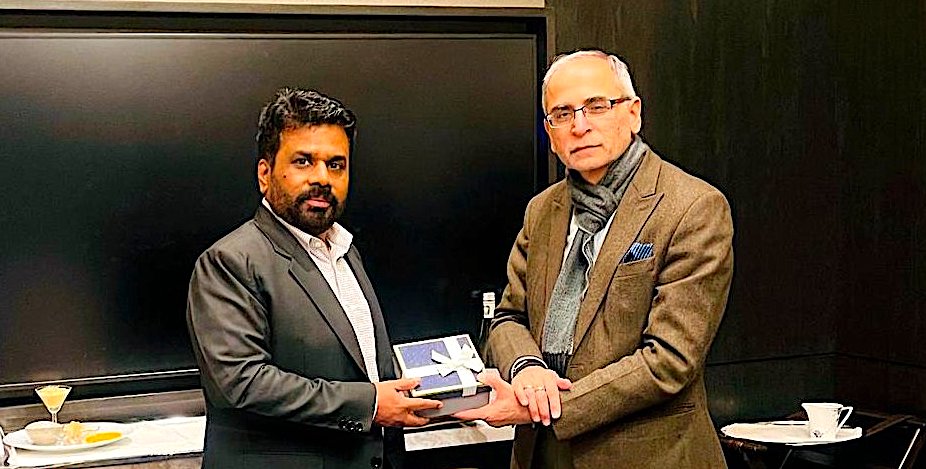

Photo courtesy of Colombo Times

When the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP) was hosted by India a couple of months ago everybody sat up and took notice, especially those old enough to recall that once-revolutionary movement’s strident, even armed, anti-Indian postures in its turbulent, twice bloody, past politics. The public’s attention was drawn to this infrequent episode in inter-country ties since it is not often that a country’s political organisations get such invitations.

In this first part of a two part article, the current relations between India and Sri Lanka is looked at in terms of the evolving bilateral relationship. It is also a preview of impending specific developments in these relations in the light of the ongoing Indian Lok Sabha elections and the likelihood of the Sri Lankan presidential elections being conducted in October or November this year.

All opinion polls and electoral analyses indicate that the Lok Sabha polls is expected to see the continuation in power (although with a possible reduced majority) of the incumbent Bharatiya Janata Party-led National Democratic Alliance (BJP-NDA). In Sri Lanka, the few opinion polls so far held indicate that the forthcoming electoral contest, both presidential and possibly a parliamentary general election, could herald a substantive political change in the arrival in power of a political force hitherto untested in both national governance and in international relations.

The one-time Marxist revolutionary political party, the JVP, is seen as the political force most likely to win the forthcoming elections, contesting at the helm of a new movement registered as the National People’s Power (NPP). This will be a historic first time in power for the JVP after decades of being on the margins due to its anti-systemic political agitation.

The JVP’s originally radical Marxist enterprise beginning in 1969 included two successive insurgencies, the first in 1971. The more impactful second insurgency in 1987-1990,provoked a state military dirty war that was as bloody, in a shorter time period, as the parallel, decades-long, Tamil secessionist insurgency and state counter-insurgency.

The JVP’s long marginalisation as a subversive entity, its more recent transformation as a moderate, civil-political movement and its current emergence as the force closest to the reins of power in the immediate future is the backdrop for the NPP’s visit to India in February this year.

The Indian public did not take notice at all of the visit, except for some cursory commentary in a few English news organs in Delhi (The Diplomat) and Chennai (The Hindu). In contrast in Sri Lanka the news media of all three languages, especially the mainstream political commentary columns and public discussion on web media, literally boiled over for several weeks.

Public discussion

The public discussion in the traditional news media was seriously analytical both positively and negatively. It was paralleled, on a bigger scale, in terms of content volume by a vociferous as well as crudely satirical popular discourse in websites and on social media. That spontaneous online discourse on a foreign relations topic, especially in the vernacular is a new phenomenon and it deserves thorough dissecting.

In fact, that imbalance in public attention in the two countries is part and parcel of the necessarily unequal bilateral relationship. The Sri Lankan public has not bothered with the lack of attention by the Indian public although it must be galling for those champions of the NPP. It is likely, given the fear many Sri Lankans especially the Sinhalese, have for India as a historic dominator over Sri Lankan affairs, that this lack of attention is reassuring.

A good example of such public awe of our big neighbour was the unease among many Sri Lankans at all levels over the sudden questioning of Sri Lanka’s ownership of Kachchativu and other Palk Strait islands during the ongoing Lok Sabha elections campaign. Regular India watchers were unsurprised and saw this brief, minor, rumpus as an electioneering gundu by the BJP and its South India allies (especially in Tamil Nadu) aimed at embarrassing the Congress and its allies in the South.

Indian officials were quick to downplay those election platform remarks as of no official relevance. But various Sri Lankan interest groups from the fisheries industry to their political leadership and private sector seabed mineral prospectors still breathed sighs of relief when the issue went no further.

Delhi

The actual delegation that went to India was officially representing the NPP party that is currently holding a few seats in the current parliament. The NPP is led by the JVP and was formed by it in a classical Marxist political strategy of setting up more widely acceptable front organisations that are only indirectly linked to the more radical parent movement.

Most Marxist political movements, at one time, practised this political strategy as a kind of deliberate politico-military and ideological articulation of organised action. Some local liberal analysts, unaware of this hoary Marxist-Leninist revolutionary struggle tradition, could not explain the NPP-JVP relationship.

The logic and viability of such a front organisation strategy is acknowledged by political analysts (including counter-insurgency strategists) across the board. Most Marxist movement across the world conduct their politics in this manner, a strategy that is copied by other, non-Left political forces as well.

An example is the African National Congress (ANC). The ANC is the front organisation of the South African Communist Party (SACP) and is still controlled by it.

The JVP has several such fronts, one of which was its armed wing, the Deshapremi Janatha Vyaaparaya (Patriotic People’s Movement), under which the JVP’s second insurgency was undertaken.

Today the NPP has successfully served to present a new, non-militarist, civilian-political and soft Left version of the old JVP. The NPP, being mainly fresh faces in the public eye, finds it easier to distance itself from the JVP’s past.

Transformation

This transformation, partly also due to the time lapse after the militaristic and nationalistic JVP of 1971 and 1987 rebellions, successfully presents to the voters a combined NPP-JVP movement that is no longer weighed down by the old baggage of bloody violence, arbitrary local politics and inner party authoritarianism.

Such characteristics do not sit well with a political movement aspiring to governmental power and practise of international relations in the world community within the currently globally dominant liberal political-economic framework. Likewise, those foreign powers that would have to deal with whoever is in charge in Colombo will also need clarification about the calibre of the new regime and its ideological tenor.

If the recent few public opinion polls are any indication – together with other markers as public messaging online and mass participation in movement events – this re-made JVP turned NPP is now on the verge of being voted into power.

Current political speculation places the NPP-JVP on track to take power either entirely on its own or in coalition with some parliamentary support by lesser political fellow travellers. Even if the NPP is edged out by a liberal-capitalist combination led by Sajith Premadasa’s SJB coalition, the NPP is certainly on track to take second placing in the national political firmament.

This prognosis is yet to be affirmed by substantive hard data. In the absence of such data, there is only the limited data from a very few surveys and perceptions by experienced analysts.

Hindutva

How will a Hindutva nationalist, neo-liberalist and somewhat introverted regime in Delhi deal with a largely secularist, social democratic (as opposed to neo-liberalism) and Marxist-influenced regime in Colombo?

Delhi is keen to find out and the recent hosting of a NPP delegation is the logical first step to learning about the NPP’s policy outlook as well as its leadership calibre.

The itinerary of NPP parliamentary leader and emergent political star Anura Kumara Dissanayaka and his three colleagues of the NPP is significant. They first went to Delhi. Then they inspected diary farming in Gujarat – Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s home state. Finally, they visited once leftist Kerala.

It was in Delhi that the NPP faced the geopolitical test: meetings with the suave but intellectually formidable External Affairs Minister Subrahmanyam Jaishankar, previously a veteran diplomat and the equally accomplished National Security Adviser Ajit Kumar Doval, previously famous as Delhi’s professional spymaster heading the Intelligence Bureau. The NPP was grilled by experts at meetings with two Delhi thinktanks. Not many Sri Lankan political delegations can impress as much as the NPP leadership can.

The NPP did not visit Tamil Nadu, often the second stop after Delhi for Sri Lankan politicians visiting India. Why did the NPP-JVP leave out Tamil Nadu? If they had asked, it would certainly have obliged. The answer is simple. Neither the NPP nor the JVP ever discusses the ethnic question, which is the number one topic of any aspiring Sri Lankan political party right up to Mahinda Rajapaksa’s first presidential election campaign.

Once the LTTE was defeated not just the separatist insurgency but the entire ethnic conflict was forgotten by much of the dominant Sinhala mainstream. So much so that the recent aragalaya for system change was an entirely Sinhala-centric movement with no mention of ethnic injustices or even class or gender injustices in the system.

Ethnic equality

The JVP of the past during its more orthodox Marxist period of the 1970s did emphasise ethnic equality and a non-religious politics. But it was still discriminatory, describing the hill country Tamils as non-Sri Lankan.

To the JVP’s credit, other than that past exclusion of the hill country Tamils, it has never explicitly articulated a Buddhist or Sinhala exclusivism in any of its political mobilisation throughout its existence. When the second Mahinda Rajapaksa regime thought of expelling Northern origin Tamils from Colombo city, it was only the JVP that strongly condemned that move as racist.

The JVP has consistently been strongly anti-India from its inception. One of its founding principles was opposition to the regional hegemonism of the Indian capitalist class. What it called Indian expansionism. That anti-Indian trope peaked with the launch of the second JVP Rebellion in 1987 under the leadership of its offshoot, the DJV. The DJV insurgency was purely a Sinhala nationalist opposition to the Indian military intervention through the Indian Peace Keeping Force.

It was a bitter irony that at one moment in our modern history there were two parallel nationalist, anti-state, insurgencies both in opposition to the IPKF and the Sri Lankan state forces. An even worse irony was that while the LTTE took on both the IPKF and the Sri Lankan forces, the JVP only fought against the Sri Lankan forces.

What if both insurgencies had combined forces? The harsh logic of general state military superiority is such that such an alliance of rebels would still have been ultimately defeated.

Anti-Indian

Almost until their delegation took wing to Delhi, the JVP had not quite given up on its anti-Indian stance. But for long that stance was no longer publicly advocated. When questioned about it in recent months, the NPP-JVP has given vague responses. Its recent hostility to large scale Indian appropriation of economic projects was in terms of the JVP-NPP’s general opposition to the control of Sri Lankan assets by foreign entities rather than a specifically anti-Indian stance.

Why doesn’t the NPP-JVP see the need any longer to convince their mainly Sinhala mass base on the India threat issue? Because over the decades, over the generations, and most critically over the evolution of both ethnic differentials and class characteristics, India is no longer the same bogey that it once was for the politically most decisive social group, the Sinhalese. This is the most critical ideological dimension at play when the JVP deals with India today.

Firstly, the complete defeat of Tamil nationalist militancy and the current military dominance of Tamil areas has removed that crucial existential threat perception among the Sinhalese. Secondly, this ethnic threat ended at a time when the socio-economic development had begun to benefit the (most advantaged) Sinhala society.

When the Sinhalese won the war they found themselves in a richer social condition to better enjoy their new-found national supremacy. That also explains their rage when they soon found that the regime-led plunder had quickly deprived them of that enjoyment.

The JVP-NPP is the political beneficiary of this socio-economic evolution, especially post aragalaya. It has found that the social base in which it had always been rooted has evolved in this socio-economic and ideological manner.

The anti-Tamil sentiment had subsided because the military victory had (if temporarily) erased the fear of Tamil dominance. More significantly, the Sinhalese no longer see Sri Lankan Tamils as a viable agent of Indian expansionism. This is because, India itself has evolved socially, economically and politically. This parallel development is critical.

Twenty years after the Tamil secessionist war era, India is more recognisably a great power. The watching Sinhala dominated society has appreciated India’s economic, technological and military development. The integration of the Indian regions and states into a thriving, gigantic, national capitalist economy has presented a more unified India.

That unity also expresses itself in a majoritarian Hindu-Hindi dominance. When a Sinhala beauty queen becomes a Bollywood star and a budding Sinhala pop starlet becomes an Indian singing sensation overnight, things get easier for the Sinhalese to lose their fear of the Indian hegemon.

Sihalathva

The politico-ideological moment has arrived where an island ethnic hegemon can now identify with the sub-continental ethnic hegemon. The consolidation of the Hindu-Hindi majoritarianism in Delhi parallels a similar consolidation in Sri Lanka. The reign of Hindutva is now paralleled by the reign of Sihalathva.

The Sri Lankan majority vote bank can identify with Delhi especially when Delhi’s Vaishnava Hinduism is hostile to the South Indian Shaiva Siddhanth.

Equally significant, ethno-ideologically, has been the rise of anti-Islam in India and in Sri Lanka. In both societies the anti-Islam plank is embedded in the ethno-supremacism of the majority ethnic communities. Hindutva leads the demonising of Muslims in India and the Sihalathva forces do the same in Sri Lanka.

For all these reasons, the NPP-JVP can now flaunt its rapprochement with the BJP regime in Delhi as an accolade before its principally Sinhala audience. That once bitter pill of Indian expansionism is now easier to swallow because the NPP’s vote bank to possible victory is finding a new flavour in that pill.