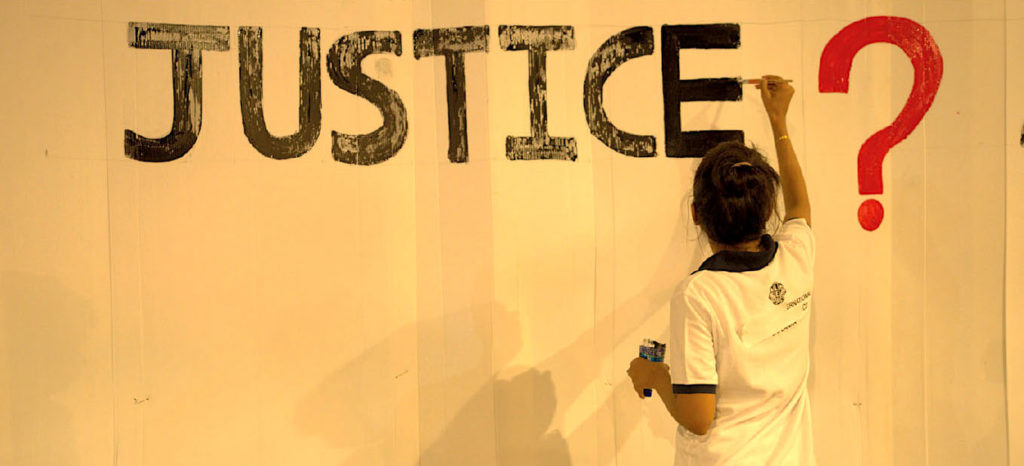

Photo courtesy of LMD

January is usually a grim indication of the perilous state of human rights in Sri Lanka. It is reminder of the many cases that have gone unpunished with perpetrators still at large. On January 8, the Sunday Leader editor Lasantha Wickrematunge was killed in Colombo in 2009. Former Rivira editor Upali Tennakoon was assaulted by motorcyclists in January 2009 while during the same week five young men were killed in Trincomalee in 2006. Political cartoonist Prageeth Eknaligoda disappeared in January 2010 and hasn’t been found yet.

The security forces and other state authorities are accused of being involved in these cases. “They are emblematic of the failure of the Sri Lankan criminal justice system, the impunity enjoyed throughout the political spectrum and the inability of the judiciary to deliver justice to victims of violence orchestrated by the state,” said a hard hitting editorial in the Financial Times.

Two people stand out as having command responsibility for the crimes that took place under their watch – Gotabaya Rajapaksa as Secretary to the Ministry of Defence and President Mahinda Rajapaksa as head of state. In the cases of Lasantha Wickrematunge and the disappearance of Prageeth Eknaligoda, evidence in the courts shows that military intelligence units were responsible and that there was a political motive. Politicians are in league with the military to cover up evidence and hamper any investigations, as can be seen by what happened to former head of the CID Shani Abeysekera who investigated Prageeth’s abduction, which resulted in indictments against military officials implicated in the crime. Mr. Abeysekera was hounded out of a job and is still being persecuted to the deafening silence of then opposition leader Ranil Wickremesinghe under whose government the investigations had progressed. “The bipartisan collaboration to stall investigations, protect perpetrators and cover up crimes is visible as day just as it is obvious who ordered the above crimes,” the Financial Times editorial said.

However, January 2023 has shed some light at the end of tunnel. Canada announced it was sanctioning Gotabaya Rajapaksa, Mahinda Rajapaksa, Staff Sergeant Sunil Ratnayake and Lieutenant Commander Chandana Hettiarachchi for “gross and systematic violations of human rights during armed conflict in Sri Lanka, which occurred from 1983 to 2009” while the UN has demanded information on “alleged enforced disappearances, arbitrary detentions, torture, and extra-judicial killings, reportedly committed by Government security forces between May 1989 and January 1990, in the Matale District, in the context of the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP) uprising.”

In another small flash of light, in December last year, the Vavuniya High court, in response to a Habeas Corpus petition, ordered the Army to produce a person who was handed over to the armed forces in Mullaitivu by his family members during the final stage of the war. The judge said that the court had reasons to believe that the person was in the custody and control of the armed forces after a witness testifying on behalf of the Army admitted to a register that documented those who surrendered on that day but failed to submit such register before the courts. If the respondents failed to produce the person in court, the court said the respondents should explain the circumstances surrounding his disappearance.

These are three small but important steps on the road to truth, justice and accountability for the country’s brutal past and gives a glimmer of hope for sustainable reconciliation.

The sanctions against the two former presidents and the military men would freeze any assets they may have in Canada and forbid entry into Canada.

Staff Sergeant Ratnayake was convicted of murdering eight Tamil civilians in Mirusuvil but was pardoned by President Gotabaya Rajapaksa while Lieutenant Commander Hettiarachchi is implicated in the abduction and murder of 11 young Tamil men in 2008 and 2009.

In a case of shooting the messenger, the standard response of successive governments to allegations of heinous crimes, the Wickremesinghe administration’s Foreign Minister Ali Sabry summoned Canada’s Acting High Commissioner Daniel Bood to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and “expressed the deep regret of the government on the announcement of unilateral sanctions brought against four individuals including two former Presidents of Sri Lanka by the Government of Canada based on unsubstantiated allegations,” the Foreign Ministry said. This clearly shows that the regime is bent on perpetuating the culture of impunity that exists. By agreeing to contest upcoming local government elections under one banner, the unsavoury Wickremesinghe-Rajapaksa collaboration has been cemented for the worse and gives little hope that justice will be served under its governance.

“It’s also time countries in Asia and the Middle East stopped blindly issuing visas to the Rajapaksas; why can sanctioned individuals like Gotabaya still visit Dubai for a holiday or Singapore for medical treatment when ordinary Sri Lankans are desperate to know the fate of their loved ones and struggling to feed themselves?” asked international lawyer, Alexandra Lily Kather, who has been drafting sanctions submissions and criminal complaints for the International Truth and Justice Project (ITJP).

Following a comprehensive report by the ITJP and Journalists for Democracy in Sri Lanka (JDS) UN bodies have sent a joint communique to the government regarding its failure to hold accountable officials in charge of the Matale District for the alleged crimes. The UN statement expressed concern about what it called a “complete lack of accountability and judicial action against the State authorities identified as the main perpetrators of the violations committed.”

While the UN report has redacted the name of the commanding officer, the ITJP report names Gotabaya Rajapaksa as the commanding officer of the Matale Camp where he was the commander of the first battalion of the Gajaba Regiment in the Matale District between May 1989 and January 1990, a period investigated by four Presidential Commissions, which listed the names of at least 700 people who disappeared from the district. It also lists hundreds of alleged perpetrators from around the country but these names cannot be accessed until 2030.

Groundviews asked four human rights activists for their thoughts on the Canadian sanctions and the UN demand.

Britto Fernando, Chairman of the Families of the Disappeared

The fact that the Canadian government has imposed sanctions is good news. In the Navy abduction case, Commander Wasantha Karannagoda, the 14th accused, was acquitted; Sunil Ratnayake was convicted and then pardoned. People never thought they would be questioned in Sri Lanka. The 1996 commission on disappearances had 1,000 names of suspected culprits but the names can be released only in 2030. What is the use of that? We are happy that foreign countries are making these decisions and taking some actual action. It gives hope to families of the disappeared that cases are being kept alive around the world. The Matale mass graves case has been reopened after 30 years and this gives hope to families in Matale and all other families who have been waiting since 1971. While the Office on Missing Persons gave us some hope initially, not a single inquiry has been made so far. The government is not willing to go ahead and discover truth. Only truth, justice and accountability will ensure that these crimes are not committed again.

Ruki Fernando, human rights activist

The Canadian measures against four Sri Lankans gives effect to UN High Commissioner for Human Rights recommendations to UN member countries last year about targetted sanctions such as asset freezes and travel bans against those credibly alleged to have committed rights violations. These measures are long overdue and are too little. Canada and other countries must do more to advance rights, accountability and justice in Sri Lanka, including through universal jurisdiction and supporting the investigation of economic crimes and tracing and recovery of stolen assets. The four individuals targetted are two former presidents, a navy and anarmy officer – all persons who generally enjoy immunity for serious crimes. Many Sri Lankans who have been denied justice for decades have been seeking international measures and this is small victory for them. International measures such as these poses challenges to Sri Lankan institutions such as investigators, prosecutors and judiciary to do more to fullfill their duty to ensure justice to Sri Lankans, inside Sri Lanka.

Jehan Perera, Executive Director of the National Peace Council

The Canadian sanctions against two former presidents and two mid level military officers are an indication of the wide sweep of international human rights sanctions. It shows that problems of accountability and human rights need to be dealt with. They cannot be ignored or dismissed as they will not go away once they are raised. These sanctions come as a warning to those in government and positions of authority that they cannot act with impunity and get away with it, either because they are too high or because they are too small.

Bhavani Fonseka, lawyer and Senior Researcher at the Centre for Policy Alternatives

The targeted sanctions imposed by Canada on four individuals sends a strong message that the government has failed to deliver on accountability and human rights. It also signals that no one is above the law and that even a former head of state can face sanctions for their role in past violations. This is in a context when successive governments have made countless promises to address justice, peace and human rights but multiple challenges remain in realising this in Sri Lanka. Even the few cases that progress through the criminal justice system face setbacks as seen with the pardoning of Sunil Ratnayake by then President Gotabaya Rajapaksa in 2020. This has resulted in an entrenched culture of impunity with victims having no confidence in domestic initiatives. It is now incumbent on the government to take genuine steps to reckon with past abuses. This must entail both structural reforms and initiating investigations and prosecutions without the threat of political interference. Inability to take such steps is likely to send the message that the government is complicit in the impunity and further derail chances for peace and reconciliation.