Photo courtesy of Amnesty International

As the United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC) prepares to meet, the regime’s multiple failures to protect and respect Sri Lankans are under local and international scrutiny. A hard-hitting report from the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights has pointed out that causes of the economic crisis include “impunity for human rights violations and economic crimes” and the vital necessity of “justice, reconciliation and human rights”. Amid ongoing militarisation, repression and lack of accountability for abuses, firm action is urged by the international community to safeguard Sri Lankans if the regime continues not to do so.

Despite some gestures in the lead up to the UNHRC’s 51st regular session, which will run from September 12 to October 7, such as modest constitutional reform to reduce presidential powers, the government’s stance has been largely defiant. This includes use of the discredited Prevention of Terrorism Act against dissidents, refusal to allow proper investigation of disappearances and other acts of extreme violence largely affecting minorities, appointment of ministers facing allegations of serious crimes and lack of care for people suffering severe poverty.

Ex-president Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s return to the island has drawn attention to the continuity of the previous administration with that headed by Ranil Wickremesinghe, who had helped prop up his rule as public anger grew. In 2015, Mr. Wickremesinghe’s government co-sponsored a resolution agreeing to a joint investigation of alleged abuses, drawing on overseas support. However the foreign minister of the regime he now heads, Ali Sabry, declared that it would not cooperate with the UNHRC in any international investigation. Ali Sabry was Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s lawyer, and served under him as minister of justice)

After UNHRC has repeatedly failed to persuade those in power in Sri Lanka to respect the human rights of those they govern, and in view of the dramatic effect of bad governance of economic as well as political rights, patience is wearing thin. As damaging evidence mounts up, the UN and members states are being urged to take stronger action, including by Tamil parties urging a referral to the International Criminal Court. A draft resolution on Sri Lanka is expected, possibly on September 23, which might be voted on by member states on October 6. The regime’s strategy of making slight concessions but pressing ahead with human rights violations carries high risks.

Strong criticism and damning evidence

Journalists for Democracy in Sri Lanka (JDS) is among the organisations that have recently drawn attention to ongoing abuseswith a detailed Submission to Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. According to JDS, the roots of the current human rights crisis go back many years, as a ruling elite upholding Sinhalese Buddhist supremacy (although propped up by a handful of people from minorities) allowed successive governments and the armed forces to get away with appalling acts. The international community was urged “to demand that a) in the short-term there is accountability not only for corruption and abuse of power, but also for mass atrocity crimes; and b) that long-term reform of the state will embrace institutional reform including institutions to combat impunity, to restructure the present ethnocratic system by sharing power to prevent atrocity crimes and group discrimination in the future. Long-term reforms should also downsize the military of a country that utilised 10.3% of government expenditure in 2020 for the military.”

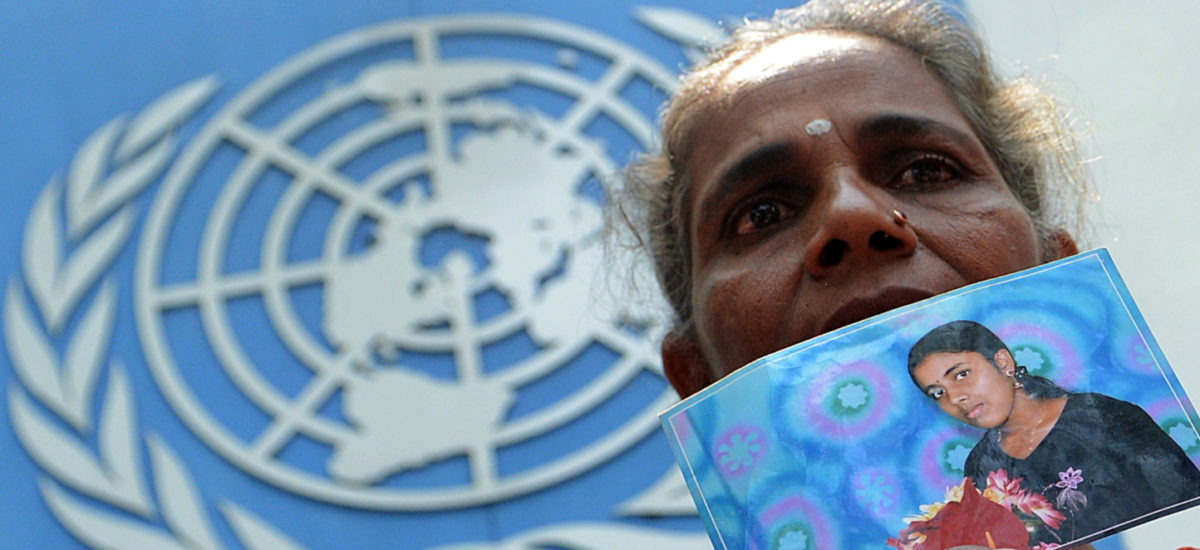

Amnesty International issued a briefing on the recent crackdown on protesters, while the Public Interest Advocacy Centre has produced a grimly informative map locating thousands of reported human rights violations from 1983 to 2009.

However the official report by the outgoing Commissioner, dated September 6, has received even more media attention and will be hardest for the authorities to ignore.

As the summary states, “Sri Lanka is experiencing an unprecedented economic crisis and is now at a critical juncture in its political life, bringing into sharp focus the indivisibility of human rights. Since March 2022, Sri Lankans from all communities and walks of life, in particular young people, have come together in a broad-based protest movement to demand a change of government and call for accountability and deeper reforms. Meanwhile victims of past human rights violations continue to wait for truth, justice and redress.”

The government is urged “to embark on a national dialogue that would advance human rights and reconciliation and to carry out the deeper institutional and security sector reforms needed to prevent the recurrence of violations of the past”, the international community “to support Sri Lanka in its recovery, but also in addressing the underlying causes of the crisis, including impunity for human rights violations and economic crimes. By pursuing a number of options to advance accountability at the international level, Member States can help Sri Lankans seek justice, reconciliation and human rights.”

Human and economic rights are vital

In the report, this is followed by an introduction and outline of the context, including “mixed signals” from the new leadership which took over after the former president fled, then a section on the “Human Rights Impact of the Economic Crisis.” This highlights the close connection between economic, social and political rights. The right to food, health and nutrition, education, access to a basic household income and essential items have been affected and some problems may get worse if a bailout package is agreed that falls short of basic human rights standards.

“Sri Lanka will now face painful economic reforms, which will impact on human rights and likely be a focus for further protest. As the Government negotiates an economic recovery plan, it must be guided by its obligations under the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural rights (ICESCR),” the report states. Any austerity measures must be “temporary, necessary, proportionate and non-discriminatory, and be compatible with the core content of the rights recognized in the ICESCR, and such measures should not impinge, disproportionately, on the rights of the most disadvantaged and marginalized groups and individuals.”

While the international community should “support Sri Lanka in its recovery” in a way which protects the vulnerable, the importance is also underlined of “addressing the underlying governance factors and root causes, which have contributed to this crisis and that she has highlighted in previous reports. These include the deepening militarization and lack of transparency and accountability in governance, which have embedded impunity for serious human rights violations and created an environment for corruption and the abuse of power.”

A section on “Human Rights Trends and Developments” follows, including legal and institutional changes. According to this, “more fundamental constitutional reform is needed to strengthen safeguards for effective separation of powers and devolution of political authority”, while use of the draconian Prevention of Terrorism Act has alarmingly resumed. The report indicates that militarisation continues to undermine democracy, with particularly serious effects in the North and East; inclusion and reconciliation are vital; intimidation and threats to former combatants, civil society and victims are ongoing problems; and grave concerns also remain with regard to freedom of expression, peaceful assembly and law enforcement.

The report goes on to examine gaps in “Reconciliation and accountability”, with ongoing failure to take substantial action to resolve past abuses and rebuild confidence in minority communities; or on emblematic cases. There has been “no further progress to establish the truth and investigate the terrible Easter Sunday bombings in 2019 despite the fact that church leaders and victims continue to demand a complete and transparent account of the circumstances that allowed those attacks and the role of the security establishment.”

A project team has been at work gathering information (despite being refused permission by the Sri Lankan government to visit), collating and cross checking evidence, advocating for victims and survivors and responding to requests from national authorities on alleged perpetrators. What individual governments and international bodies might do to further the cause of those denied justice is examined, including overseas prosecutions, targeted sanctions for people who are credibly alleged to have been responsible for gross violations and abuses and initiatives to empower victims and civil society.

Moving forward

In its conclusions, the report offers hope for a better future: “The broad-based demands by Sri Lankans from all communities for accountability and democratic reforms present an important starting point for a new and common vision for the future. The High Commissioner believes there is the opportunity for a new meaningful national dialogue on how Sri Lanka can be transformed into an inclusive, pluralist and fully democratic State based on accountability, the rule of law, non-discrimination and respect for human rights in which an environment for freedom of expression, peaceful assembly and democratic participation will be essential.”

However impunity for those violating human rights “remains a central obstacle to the rule of law, reconciliation and Sri Lanka’s sustainable peace and development, and remains the core risk factor for recurrence of further violations.” In this context, “Without an effective vetting process and comprehensive reforms in the security sector, serious human rights violations and atrocity and economic crimes risk being repeated as the State apparatus and some of its members credibly implicated in alleged grave crimes and human rights violations remain in place.”

The Sri Lankan authorities are urged to act now to secure human rights, including taking “all necessary measures to guarantee people’s economic and social rights during the economic crisis; ensure immediate relief for the most marginalized and vulnerable individuals and groups based on non-discrimination and protection of human rights, and strengthen social protection by increasing financing and extending it to cover emerging needs.” Slashing military spending and tackling corruption, moving forward on investigating high profile past abuses and protecting basic freedoms are proposed.

Meanwhile previous recommendations to the UNHRC and member states from 2021, which included protecting asylum seekers at risk of reprisals and examining options for judicial proceedings and targeted sanctions such as asset freezes and travel bans, were reiterated. Further suggestions were added included asking the Office for the High Commissioner for Human Rights to monitor steps to address economic crimes that have impacted on human rights, reinforcing capability to work on accountability for human rights violations and supporting Sri Lanka in tracing and recovering stolen assets.

Clinging to the past and what happens next

The leadership’s actions in recent days have not held out much hope of substantial progress, despite the odd conciliatory gesturesuch as toning down presidential powers.

For example, of 37 new ministers appointed (itself a controversial move, given the supposed need to cut spending), as Human Rights Watch pointed out, three are implicated in serious rights abuses. Pillayan (Sivanesathurai Chandrakanthan), a former Tiger fighter who later joined a pro-government armed group, allegedly conscripted child soldiers and helped murder an MP, while last year Lohan Ratwatte threatened prisoners at gunpoint and Sanath Nishantha is under police investigation for a violent attack in 2022. The others include a nephew of Gotabaya Rajapaksa, Shasheendra Rajapaksa, an ex-minister whose most notable achievement was enforcing a ban on chemical fertiliser and hence helping to wreck agriculture and the economy; he is now minister of irrigation.

While attention has been paid to any shortages affecting the elite, the government’s lack of concern for ordinary people struggling to make ends meet has been noticeable. This is in contrast to the concern shown by so many on the island and across the globe. UNDP has been worried enough to work with local partners on a crowdfunding appeal to help meet urgent food and healthcare needs.

Yet some of those in charge in Sri Lanka will not even recognise that there is a serious problem. UNICEF has been desperately trying to raise funds to help Sri Lankan children, pointing out that even before the crisis, it was estimated as having among the highest rates of child malnutrition in Asia, while working with local partners to care for the most disadvantaged. Health Ministry Secretary Janaka Sri Chandraguptha questioned the data used claiming that, “Unlike other countries, there is no risk of death and disease among children in Sri Lanka due to emaciation, and there is no risk of acute malnutrition such as marasmus or kwashiorkor”. In response Dr Chamil Wijesinghe of the Government Medical Officers’ Association pointed out that although there were differences with regard to statistics, it could be clearly observed that people were facing a problem in terms of food supply.

Such a cavalier attitude to the basic rights of Sri Lankans and principles of good governance by those in power will prove costly at the UNHRC. Some states in the Core Group working on Sri Lanka (Canada, Germany, Malawi, Montenegro, North Macedonia, the UK and the United States) have already raised concerns about repression that have been ignored. While the Chinese government will continue to back Sri Lanka at the UN, along with some others, a stronger resolution than before may well be passed as willingness in the international community, as well as Sri Lanka itself, to keep waiting for change fades.

For further reading, and a commentary on the first week of the UNHRC gathering in Geneva, see:

UN Human Rights Council Urged to Take Firm Action on Sri Lanka