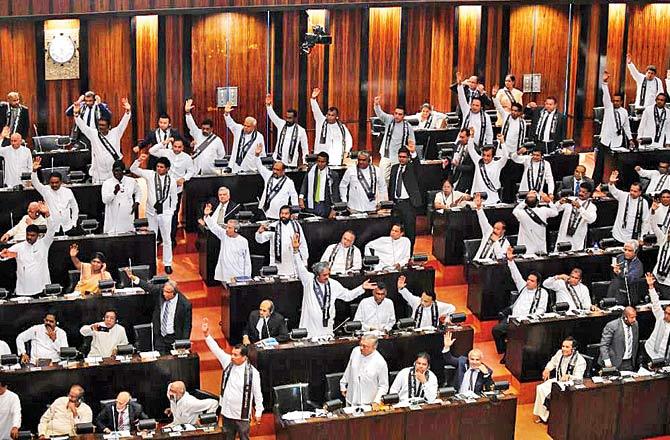

Photo Courtesy of Midday

The proposed 20th Amendment has several major defects. One of its key faults is that its sponsors and framers have chosen a very wrong approach to constitution making.

There are several reasons why this approach is wrong.

The first is the refusal to learn constructive lessons from the past constitutional reform experiments. The lessons that seem to have been learned are all the wrong ones. The second is that the framers of the 20A are not animated by the larger democratic interests of the political community which Sri Lankan people constitute collectively. Instead, the primary motivating factor seems to be political self-interest. The third is that the proposed Amendment is totally devoid of a democratic normative framework relevant to our society and its own progressive-modernist legacies of constitutionalism. Instead, in disinheriting the progressive legacies of our society’s modern political and social life, it builds itself on one or two dreadful and destructive experiments of constitution-making in the recent past.

Lessons from the Past

Sri Lanka has a relatively long history of unmaking, making and amending constitutions. They offer a rich array of lessons about what to be avoided as well in constitution-making.

Both the First and Second Republican Constitutions of 1972 and 1978 together and individually offer the following lessons:

- Any popular mandate for a new constitution should not be interpreted as license to undermine or remove the democratic checks and balances in the exercise of political power. The reason is quite clear: it would encourage rulers and bureaucracies to violate with impunity citizens’ freedoms and liberties. Such misuse of the popular mandate is certain to produce tyrannical consequences and ultimately will erode the legitimacy of the government itself.

- Undermining the rule of law, weakening the independence of the judiciary, and making the accountability institutions subservient to the executive will initially please the egos of the politicians and officials, but in the long run are bound to create a deep chasm between the government and the citizens, rulers and the ruled.

- The eventual political cost of ignoring minority demands for political equality and equal citizenship rights in a constitutional scheme can be quite high. It will create a condition of unending ethnic tension in society as well as between the state and the alienated minorities.

- Constitutions with undemocratic intents as well as content will harm the legitimacy of not only the government in power, but also the prevailing system as a whole.

Lessons from 1978C and its 18A

Both the original 1978 Constitution and its 18th Amendment, together as well as individually, offer us the following lessons:

- Any ruling party or government that ignores the golden rule of democratic governance that (a) political power is NOT unlimited and that (b) the right to, and exercise of, political power has inherent limits will do so only at its own peril.

- Any new constitution, or any major alteration to an existing one, should not be designed to please the personal desires (‘whims and fancies’) of an individual, however powerful he or she may be at the time of constitution-making. A constitution thus designed is certain to come into conflict with the actual and objective needs of society as well as aspirations of its citizens.

- A new constitutional scheme should not be designed to serve only the interests of newly emerged wealthy elites in society. When a constitution becomes an instrument of the political ambitions of wealthy elites, it runs the risk of providing legality to despotic governance.

Lessons from 19A

There are three lessons to be learned from the process of making the much-maligned 19th Amendment:

- Wide consultation in the drafting process is not only useful, but also helpful to improve the level of democratic health in the polity.

- It is always better to build consensus across all political parties in parliament for a major Amendment or a new constitution. Constitutional consensus-building in a deeply divided polity like ours is a frustrating and time-consuming political exercise. Yet it enables all, or a majority of, the stakeholders to take part in the process, make their inputs, and claim some ownership to the outcome, although for partisan political reasons, some might later withdraw from the consensus.

- If the consultation and consensus-building in constitution-making is not politically managed with clarity of purpose, the overall goals of the constitutional compromise may run the risk of producing a constitutional scheme with potentially harmful internal anomalies and contradictions.

- A Democratic constitution-making exercise today needs, more than ever, an unwavering political leadership to champion it through to the end by innovative and imaginative democratic means. The reason is a paradoxical one. Alternatives to democracy are also competing with democracy, with enormous material resources, to gain popular support and loyalty through democratic means. In this age of Right-wing populism, media-manufactures popular consent and manipulation of public perceptions through information pollution, post-democratic alternatives tend to gain easy currency and public legitimacy.

Constitutions and the Political Community

A Constitution for a country is in the final analysis a constitution for the entire political community within a country. Although the basic nature of that constitution may be conceptualized by a ruling party, to be sustainable and be able to survive post-regime change shocks, it should not reflect only the agenda of that ruling party.

Rather, a Constitution should embody the higher goals and aspirations – ‘noble ends’ — of the political community, that are open to be shared by the vast majority of members of that political community, notwithstanding the momentary shifts in their political judgement expressed at periodic elections.

A Normative Framework Needed

A good constitution is always a democratic one. A good democratic constitution for Sri Lanka should be guided by a normative framework that usually embodies a synthesis of normative values the people of our political community have inherited from our own liberal democratic, republican and social-egalitarian traditions that have been evolved through our own political modernity.

The Indian and South African constitutions are model post-colonial constitutions that are guided by such a value synthesis, derived from the best traditions of modern constitutionalism as well as egalitarian and social-justice impulses inherent in their local cultures and histories.

What Legacy? What Inheritance?

Finally, Sri Lankan constitution-makers should not consider the South-East Asian developmentalist authoritarian state model as a new constitutional template for Sri Lanka, because it goes against our own progressive constitutionalist legacy evolved during the past century or so.

What needs to be inherited and further advanced is that progressive strand of constitutionalism which we can claim as authentically modern and local. It appears that the framework of 20A have sought inspirations from wrong constitutional models, at home and abroad, that are devoid of any normative content.

The Supreme Court where the constitutional validity of the proposed 19th Amendment will be examined and debated is perhaps an eminently suitable forum to raise these points as well. In a number of previous judgements, and as recently as December 2018, our Supreme Court has repeatedly validated the inherent normative framework of Sri Lanka’s own tradition of democratic constitutionalism.

Alerting our Honourable Justices, who make up the much revered public institution that is the last bastion of citizens’ freedom and democracy, should also be a part of the struggle for inheriting and defending our own best legacies of political and social modernity.