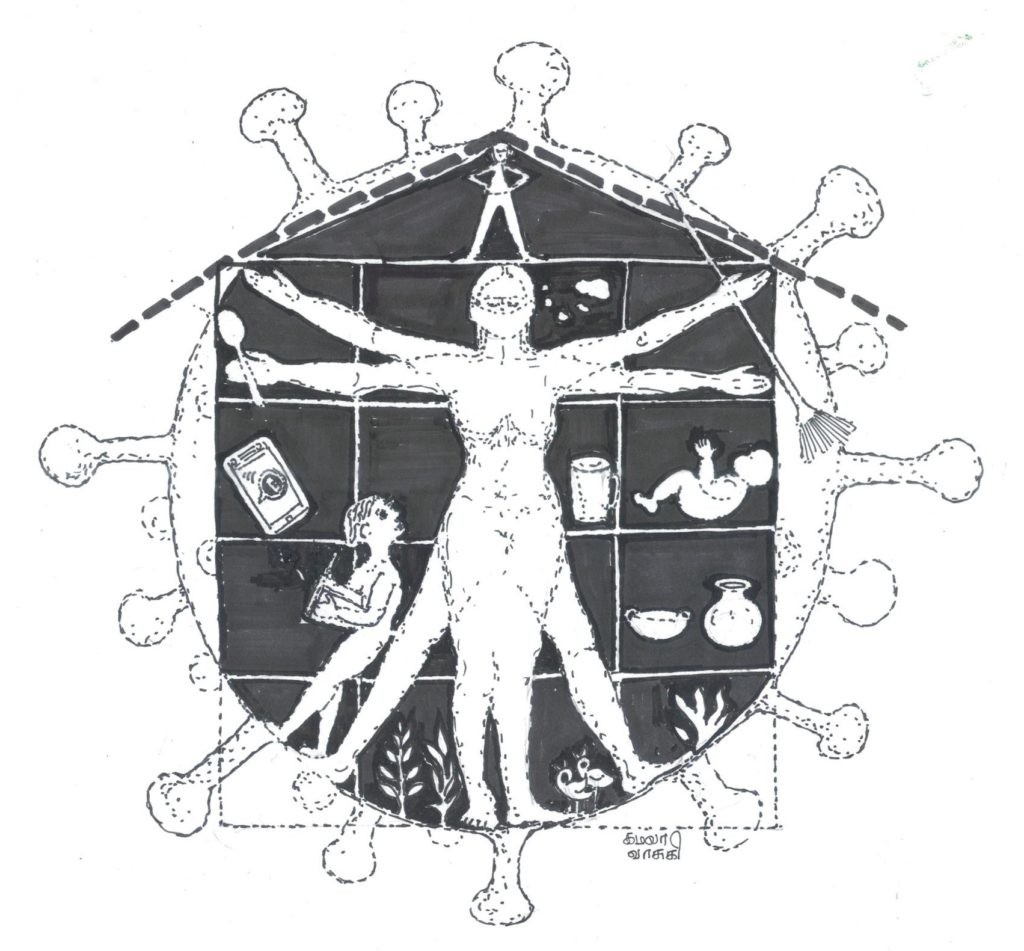

Cartoon courtesy Vasuki Jeyasankar

Sri Lanka has not been immune to the ravaging effects of the novel coronavirus, which emerged late last year and has affected millions worldwide. For the many struggling to cope with changes brought about by last year’s presidential election, this deadly disease has only compounded their problems. The gradual militarization of public institutions, continuous lockdowns, excess powers given to the police and military, and the absence of parliament and access to the judiciary have together created a normalized pathway to authoritarian rule. Economically, the pandemic has left the Sri Lankan economy in dire straits. The closure of international borders and suspension of interstate transport have dealt a severe blow to the country’s tourism industry. Exports were blocked, and our migrant workers were left stranded, with a few thousand workers sent back.

Through it all, those most marginalized in our society have borne the brunt of the burden – women. While policymakers have concluded that keeping people at home is the best way to ward against the virus, the bitter truth is the home is not safe for everyone. In addition to devastating reports of domestic violence, women working in the tea, apparel, caregiving and house cleaning sectors have found themselves uniquely vulnerable to the economic consequences of a mass shutdown. Recognizing their plight, the government must take a gender-sensitive approach to provide for those on the margins and the frontlines, no matter what policy approach to Covid-19 it ultimately selects.

Domestic Violence

A father in Ampara district killed his two children by throwing them into a well during the lockdown. Mannar police ordered a woman victim of domestic violence to return to live with her husband, leaving her with serious injuries. Children homes in the East and Northwestern province have reported that children who were sent back to their families due to lockdown have returned after the lifting of curfew with signs of severe abuse. A school in the north reported at least four teenage girls found pregnant when they returned to school. In Jaffna, police officers threatened to withdraw a complaint from a woman who was sexually and physically abused by her politically connected husband, who had good rapport with the officers.

Although domestic violence has always been seen as a regular occurrence in our society, the effects of this catastrophic period have exacerbated domestic violence and paralyzed institutional structures that address and prevent domestic violence. It is becoming impractical for women to speak out or seek justice in connection with violence, as the police department focuses more on curfew-related arrests and refuses to register complaints of domestic violence. Groups and organizations that assist women victims of violence were unable to go outside without a curfew pass and take action. Importantly, the magistrate courts and Quazi courts have been inaccessible during lock down and women suffered the most. To date some of the Quazi courts in the east are not functioning, and complaints to the Judicial Service Commission have yet to bear results. As a result, divorced women and women who have filed cases for maintenance and their families are left in a very precarious situation, relying on allowances provided by their estranged husbands. In some cases, such abandoned women are forced to have sex with their separated and estranged husbands in order to receive their allowances. Women who have escaped violence and returned to normal life are forced to return to their old lives during this time of deadly disease.

Women’s groups have always been at the forefront of fighting violence against women and children and providing physical, psychological and legal support. It is a matter of great concern that during the curfew, there were no gendered services to protect the rights of vulnerable and needy women within the definition of essential services or needs. Although essential service providers obtained permits to go out, permits and priority were not given to women rights activists and psychosocial support networks. Women development officers and child probation officers were put to work distributing rations. Although some women’s organizations were likewise permitted to deliver food and rations, they were not allowed to work on protection and rights-based work. Plainly, the Presidential Task Force on Covid-19 has failed to learn from our past disaster management experiences and written policies. To give one example of its ignorance and incompetence, the task force apparently did not think of sanitary pads as an essential item to be distributed with the ration packs.

Import and Export Economy

Women are the backbone of the country’s economy through regulated and unregulated occupations. The disease has hit the three main industries of foreign exchange earnings: tea production, garment exports, and migrant workers’ remittance. Seventy to ninety percent of those working in these industries are women. The government must implement better socio-economic security measures to rebuild the country’s economy and women’s livelihoods.

Those working in the tea estates already work for lower wages with a very depressed standard of living. Being at home without work has caused these women to struggle for food. In some tea estates, women have started boiling breadfruit to feed their children. Even if the country’s economy is revived when the pandemic ends, will the wages and standard of living rise for plantation workers (especially women) to permit a decent living?

Housemaids abroad are distinctly vulnerable. Remittances by these mostly female workers have played a large role in our country’s economic development. Yet the government has placed these women at the bottom of its priority list for repatriation. Only a few hundred were brought back during the peak of Covid-19 from the Middle East. The death toll of the Sri Lankan labor force abroad from Covid-19 is far greater than the size of our local casualties to date[1]. Yet our embassies abroad were not ready to host these workers or ensure them proper shelter. There was no evacuation plan until the receiving countries insisted on returning these workers, by force if necessary.

An organized repatriation plan could have reduced loss of life and transmission to family members back home. In addition, many migrant workers faced severe economic hardship upon their return to Sri Lanka – they were not paid salaries for over two to three months and received no assistance on their arrival. To make matters worse, the government’s attitude toward these marginalized workers has been openly hostile. One minister described these returnee workers as “Corona explosive thrown back at Sri Lanka from the Middle East”. Many described them as Corona imports.

Hundreds of people working in the Free Trade Zone were left in the lurch with no money to pay their rent, food and remittances to their families. They are currently out of work and unsure whether they will get their jobs back. The future of these women is in question, with their employment and financial stability not guaranteed. The government could have provided a temporary solution to the problem by providing them with interim relief or temporary employment. None of this has happened.

The role of Sri Lankan garment factories in meeting the global demand for personal protective equipment such as masks is seen as essential today. Women are also at the forefront of providing labor for this demand as well. While many on the margins will return to factory work to provide for their families, they cannot be sacrificial lambs in the wake of Covid-19. First of all, they should be given their lost wages and a decent living allowance since they have to find new space to rent and live close to the factories. These workers must be given safe transportation, workspaces with masks, social distancing, proper ventilation, and temperature checks of employees.

Care giving services

Women are disproportionately involved in providing labor within their family units, from caring for children and the elderly to sweeping, cooking and washing clothes. Despite the immensely important role played by care givers to individual and family wellbeing, as well as the country at large, this work is not addressed in policy agendas or considered as a contributing factor to GDP. Household labor is still considered “women’s work,” done for the benefit of loved ones without pay. This treatment cements gendered roles for women based on traditional beliefs, imposing disproportionate burdens on them to provide care services irrespective of their willingness or ability to do so. Although entire families have been quarantined at home for over two months during Covid-19, women alone have carried the burden for caring for their families. For those who work outside the home, this added burden has impaired women’s careers. A recent survey indicates that women teachers and other professionals have had less time for professional development than men due to these disparities in care giving. Women employed outside the home in care giving or cleaning sectors, too, have lost their jobs. With most workplaces still closed and professional classes working from home, these service providers have lost their jobs and face further economic instability and poverty. At the same time, some women are emerging as frontline service providers as the country returns to a new normalcy – such as the garment workers making masks and janitorial workers; these women must receive adequate assistance and protection to keep them and their loved ones safe.

Women-Headed Households

Another group uniquely vulnerable to this deadly disease are women who head families. While men have had the advantage of being able to quickly go outside and stand in line to buy necessities for their families when the curfew was relaxed, women in a similar position faced the dilemma of venturing out and not dealing with the chaos at home. During lockdown, men were disproportionately able to access curfew permits to sell farm products and essential items. Many women who own small farms and businesses lacked vehicles or funds to hire one and lost both produce and their capital as a result. These women heads of household also suffered more when public transport and inter-district transport were halted without warning, making it impossible for them to sell goods to their regular customers. Whereas men farmers loaded their products into vehicles and sold them door-to-door, women farmers unaccustomed to door-to-door sales could not make a profit after deducting money for vehicles and fuel. These women pointed out that such negative consequences could have been avoided if they had been given a certain amount of time before the curfew was enforced or notice of public transportation shutdowns. Women with small home gardens could not sell their produce and ended up giving away vegetables and fruit for free. In so doing, women heads of household are facing disproportionate economic hardship and must be given additional assistance. In short, Covid-19 has left women in Sri Lanka in a uniquely vulnerable position. The government must take their hardships into account in creating and implementing policy approaches to the Covid-19 pandemic. I offer just a few recommendations below from a women’s perspective.

Recommendations

Form a Disaster Management Working Group to prioritize immediate relief to women and children who are uniquely vulnerable in this time of crisis. This working group should solicit community input and learn from Sri Lanka’s past experiences with the tsunami, internal displacement and deadly disease where women and children consistently faced disproportionate burdens. Learning from our past, the working group must develop guidelines to prevent recurrence.

Ensure that women have equal representation in any task force, working group or committee appointed for emergency management.

- Form a Disaster Management Working Group to prioritize immediate relief to women and children who are uniquely vulnerable in this time of crisis. This working group should solicit community input and learn from Sri Lanka’s past experiences with the tsunami, internal displacement and deadly disease where women and children consistently faced disproportionate burdens. Learning from our past, the working group must develop guidelines to prevent recurrence.

- Ensure that women have equal representation in any task force, working group or committee appointed for emergency management.

- Strengthen existing government hotline services for women to seek immediate assistance in the event of domestic violence, whether through government or nongovernmental agencies, and appoint officers who can handle such issues in a gender-sensitive manner.

- Classify sexual and reproductive health services and gender-based violence services as essential services and allow such providers free movement to deliver services to affected persons.

- Provide necessary protective equipment and assistance to front line workers, such as health care and medical professionals, cleaning and care workers, especially women.

- Give needy families a monthly livable stipend until the country returns to normalcy.

- In addition to the Rs. 5,000 allowance for needy families, provide additional interim relief to plantation workers, migrant workers and those working in free trade zones.

- Establish a National Special Fund for women who have lost their jobs, lost their income and have been deprived of their salaries. This fund can be used to provide women with special loans and grants that to rebuild the businesses specially self-employment ventures.

- Implement programs to change the perception that caring and household work are only for women. Recognize women’s unpaid work in our economic indicators.

- Urgently adopt social protection measures to ensure an adequate standard of living including income supplementation, rent subsidies and eviction moratoriums, food subsidies, and free clean water and hygiene measures, including menstrual hygiene.

[1] http://www.adaderana.lk/news/65618/40-sri-lankan-migrant-workers-die-of-covid-19