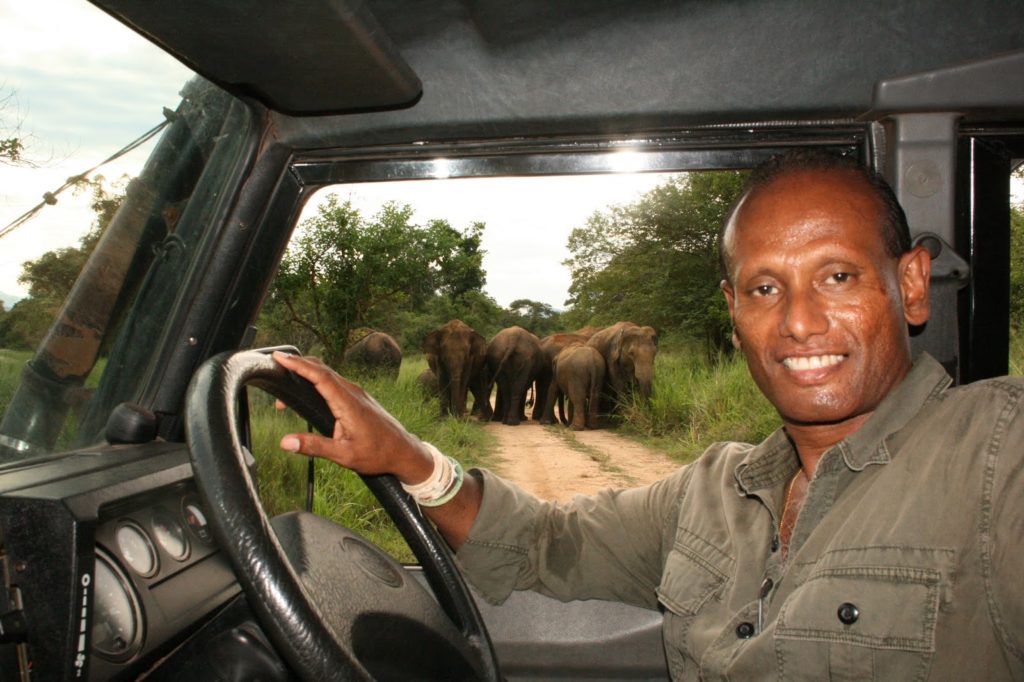

Photo Courtesy of shevlinsebastian.blogspot.com

Ravi Corea can usually be found dressed in shades of gray and green, walking stealthily through the jungles of Wasgamuwa in Sri Lanka. During my many visits to Wasgamuwa, I have observed him pausing whenever he sees elephant dung and examining it closely like a detective for clues about the elephant’s diet, age and overall health. However, since March 2020 and the arrival of the Covid-19 pandemic, Ravi has been cooped up at his home in New Jersey, unable to get to his beloved elephants.

Ravi and his organization, the Sri Lanka Wildlife Conservation Society (SLWCS), like the rest of the world, were not prepared for the pandemic. However, wildlife conservationists are trained to identify and adapt to change quickly and these traits served Ravi Corea and his organization well as they have moved quickly to address the drastic changes that the pandemic inflicted on their work.

One of the most significant changes has been the abrupt cutting off of crucial sources of funding for their conservation work. Since 2002, the SLWCS has relied on its well-respected international volunteer and intern program for funding. Much of the funds that kept the organization afloat came from volunteers and interns from around the world who saw the value in gaining first-hand conservation experience and interaction with experts in conservation, scientists, and local villagers. The pandemic brought to light the need for the SLWCS to diversify its funding sources in order to keep running.

Born in Sri Lanka, Ravi has always been fascinated by animals and nature. At 14-years-old, he remembers watching helplessly as the marshes near where he grew up were destroyed in the name of development. This was a place where he enjoyed watching birds, catching snakes and turtles, and observing wild animals. He recalled, “Just as the marsh was being overtaken that day, so too was I overtaken by the realization of how powerless and incapable I was in stopping the wanton destruction that was occurring in a place I cherished.” From that day on he was determined to dedicate his life to protecting and nourishing vulnerable ecosystems and communities.

Ravi has a degree in Conservation Biology from Columbia University in the US and spent almost 20 years at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City as a Curatorial Assistant and later as a Scientific Consultant. Ravi’s passion for wildlife led him to found the SLWCS in 1995. The SLWCS is known for the new paradigm it introduced to wildlife conservation, balancing ecosystem protection with economic development.

Making local communities living among the wildlife part of the conservation solution is something Ravi takes very seriously. The SLWCS was one of the first wildlife conservation organizations in Sri Lanka to base itself in the field; most other organizations had their base in the big cities. Before founding the SLWCS, Ravi worked in various organizations based in Colombo. He said, “I found it very ironic that all of these organizations were based in Colombo and were trying to solve conservation issues in very remote areas. Also, their efforts at the time completely overlooked a very important element, which were the communities who had the biggest impact on wildlife.” By sharing the benefits of conservation with the local population, Ravi is able to make conservation efforts sustainable in the areas where the SLWCS works.

The Ele-Friendly bus is one such initiative. The bus allows children in the Wasgamuwa area to go to school without the fear of encountering an elephant and lets elephants safely walk the ancient elephant corridor. The Ele-friendly bus is free of charge and the inside walls are highlighted with pictures to educate children about elephants and how to behave when they encounter one. The Ele-Friendly bus is an innovative project that addresses Human-Elephant Conflict (HEC). HEC happens when humans encroach onto land that was originally inhabited by elephants. The two species then have to fight for land and resources. This usually ends in violence. The Ele-Friendly bus is the first of its kind in Sri Lanka or anywhere else. It helps mitigate the intense HEC that takes place in an ancient elephant corridor in Wasgamuwa, which is now increasingly used by humans. The bus resulted in an astonishing 80% decrease of HEC soon after it launched.

Ravi, widely considered a pioneer in HEC prevention, believes that HEC is one of the most serious environmental and socio-economic problems in Sri Lanka today. He uses knowledge about the behaviors and habits of elephants to come up with solutions that benefit both the elephants and the communities.

With the pandemic raging around the world, Ravi and his team came up with E-Volunteering, an innovative solution for those who still wanted to learn about conservation but were no longer able to travel to Sri Lanka. E-Volunteers work closely with SLWCS staff and have several options including participating in research, conservation, raising awareness, technology development, writing and editing, all from the comfort of their sofas.

According to Ravi, one of the most insidious impacts of the pandemic on wildlife conservation in Sri Lanka has been the rise in poaching during the lockdown, as well as illegal logging and gem mining. Reports in the local media estimate that around 600 wild birds and animals have been killed each day since the beginning of the lockdown. The lack of food security and loss of employment are among the reasons for the rise in poaching. With no one out there to protect it, wildlife is more vulnerable than ever. Poachers are able to move brazenly within national parks and protected sites; spotted deer and porcupines are among the most poached animals.

Conservationists like Ravi are, in a sense, nature’s first responders. And not being able to be out in the field because of the pandemic has put the lives of the species they are trying to protect in greater danger. Covid-19 is likely to have long-lasting implications for wildlife conservation but Ravi is determined to keep on working – if anything he plans to work even harder to ensure the balance between conserving wildlife and the well-being of local communities is maintained.