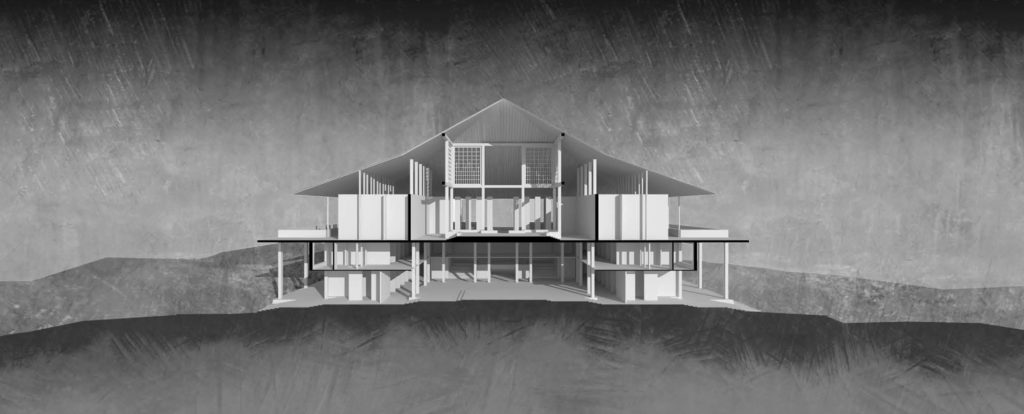

Image courtesy Corridors of Power project, which marries architecture and constitutional theory.

Sri Lanka’s current political debate on constitutional reform is significant for a variety of reasons. The Interim Report of the Constitutional Assembly has inspired a spirited opposition from Buddhist monks, reminding us of the similar opposition emerged in 1995 when professor G. L. Peiris unveiled the August 1995 proposal of the People’s Alliance government. Although Professor Peiris has changed his political beliefs beyond recognition, the leading Buddhist monks, who continue to be very vocal on matters constitutional, have not.

Meanwhile, the old politics of constitutional reform repeats itself with the parliamentary opposition pushing to the front the Buddhist clergy to fight the ideological battle on its behalf. (Or are they being backed by some sections of the government too, one wonders?). This was what the UNP did during 1995-2000. In another striking similarity with the past, the key resistance arguments are the same old ones without even new innovations in language. Division of the country, giving into the minorities, appeasing the LTTE elements and foreign powers, and diluting the constitutional position of Buddhism are the four main points of criticism.

What nevertheless impresses the political analyst is the acute sense of political interventions that Sri Lanka’s Buddhist Sangha leadership has been displaying for years and in the current debate as well. Those who want to seriously theorize Sri Lanka’s state – society relations, it is not easy to ignore the point that the Buddhist Sangha hierarchy is actually a stakeholder of the post-colonial state. This is a situation that did not exist during the colonial or pre-colonial times. It is quite unusual that Sri Lanka’s political party system and parliamentary democracy has made such a situation possible; now it is there as a political reality. That is why the existing 1978 Constitution has now become impossible to be changed democratically without the Sangha hierarchy being made a direct partner in the reform project. This creates a very complex paradox and as well difficulty for Sri Lanka’s constitutional reform exercise.

Making the Sangha hierarchy a partner in a democratic state reform process will require a massive effort on the part of a secular, democratic political leadership possessing politico-ideological clarity, democratic commitment and political will. Since Sri Lanka is legendarily short of such political leaderships, the only way out is the undemocratic option of imposing a new democratic constitution by undemocratic means, by force using the state’s coercive power, as President J. R. Jayewardene did in 1987 for the 13th Amendment and President Mahinda Rajapaksa did to get the 18th Amendment passed. I am not advocating the second option, but merely pointing to the conundrum sharpened by it. I am also reminded of the fact that the Sangha leadership did not protest President Rajapaksa’s subversion of democracy through the 18th Amendment. Actually, Sri Lanka’s contemporary Buddhist political project has no democratic content. No does it have a language of democracy to express its political aspirations. And that is also a part of the problem.

The current constitutional debate has some other interesting facets too. What I find most interesting is how the resistance to reform is also an expression of fear, uncertainty and anxieties about political-structural change. These are the sentiments most passionately articulated by the Sangha leadership of all the fraternities. The intellectuals of the joint opposition have also been giving voice to these fears in their own opportunistic ways. All these are repetitions of what happened during 1995 -2000. I think this situation forces the advocates of further devolution to re-think their arguments for devolution. The sole argument for devolution available presently is that it is necessary to lay a better and stronger institutional and constitutional framework to address the minority ethnic grievances. Although this is an eminently democratic argument, paradoxically, it immediately generates a counter argument in the Sinhalese society – aren’t the ethnic minorities the sole beneficiaries of devolution at the expence of the ethnic majority? This is an example of a classic political conundrum – a solution to one problem germinates another bigger problem.

Is there a way out of this paradox of devolution in Sri Lanka? I think there is. It is one that enables the Sinhalese majority to look at devolution through the prism of its own interests. The best argument for this is to highlight the democratic essence of devolution – reforming a centralized, bureaucratic state, which we inherited from the British colonial rule, in a manner that establishes closer linkages between the state and the citizen. Devolution, along with a strong framework of local government, has the potential to take the state closer to the community and the citizen, promote participatory governance and create the space for better state-citizen interface. It can also address the present problems of alienation that most of our citizens have been experiencing with regard to the state and its institutions. Thus, the benefits of devolution can reach all citizens irrespective of their ethnic identity. It can specifically benefit the citizens living in outer districts, and in the periphery of power structures. It will empower citizens, not just minorities or majorities.

There is also a false point being debated intensely in the current controversy. It is about the unitary versus federal models. Participants of the debate appear to be unaware of the fact that no country in the word today has pure constitutional models, either unitary or federal. This old terminology, which we continue to find in political science and constitutional law textbooks, is actually a hindrance to any imaginative discussion on a possible constitutional alternative for Sri Lanka. Besides, all constitutional models in the world are hybrid ones. India has a constitution which combines both federal and unitary features. The American constitution, though federal, has strong centralizing features due to peculiarly American factors. France has a highly centralized unitary state with a system of extensive decentralization. The UK, like Sri Lanka, has been moving away from the unitary model and embracing new forms of devolution.

All these are reflections of changing political realities of each society. Sri Lanka’s problem is that the constitutional framework is being blocked from becoming able to reflect the changing political and social realities. A key reason is that some of the key stakeholders of the state are prisoners of an outdated and binary-framework of thinking. That is precisely why they cannot make sense of Mr. R. Sambandan’s crucial compromise to accept the insertion of the word ekeeya, along with its Tamil equivalent in the new constitution. This outdated mindset has only impoverished the capacity for fresh political imagination among some influential stakeholders of the contemporary Sri Lankan state.

Let us turn to another component of this conundrum. Until a few months ago, there was a near consensus across all political parties, civil society groups and ideological forces in Sri Lankan society, that the 1978 Constitution and its Presidential system needed some democratic replacement. We are now suddenly woken up to the reality that that consensus has suffered a severe disruption. Buddhist Sangha hierarchy is the most vocal defender of the 1978 Constitution and its presidential and centralized system. President Sirisena’s SLFP too shares a milder version of this position, while the Joint opposition of former president Mahinda Rajapaksa is backing the position of the Sangha. Why has this important democratic consensus collapsed in Sri Lanka so rapidly?

Although a clear answer to this question is not yet clear, we can guess one or two tenable answers. The first is the fact that there is an emerging argument for a strong state in Sri Lanka’s post-civil war conditions and amidst the perceived threat of global Islamic radicalism. The second, linked to the first, is that an argument is emerging to suggest that the return to the Westminster model of prime ministerial government, even to a reformed one, will make the Sri Lankan state vulnerable in situations of threat to national security. The new argument seems to prefer a President elected by the entire country with a direct mandate from the people to a Prime minister who is elected by a small constituency. This argument has support constituencies within the ruling coalition, among many of the Sangha leaders and in the joint opposition.

To return to the question of managing the politics of constitutional reform in Sri Lanka, one of the tasks of which the government does not seem to be conscious is the need to provide the people of the country a creative intellectual leadership. Some people make the rather trivial point that the government is weak in marketing its message. Constitution is not a commodity to be marketed and citizens are not consumers to be persuaded by deceptive advertising. Citizens are politically intelligent beings who can be intellectually persuaded by sound analysis, morally persuasive reasoning and positive social hopes for a better political order. The government’s passionless attitude to the constitutional controversy can hardly inspire citizens.

The government’s lack of talent to advance an intellectually appealing slogan, or formulation, that can effectively capture the positive politics of constitutional reform also comes at a time when the ‘yahapalanaya’ government has lost its claims to ethical governance. The government leaders have obviously forgotten the fact that it was an ethical moment in Sri Lankan politics that enabled the Yahapalanaya coalition to dislodge President Rajapaksa’s rule in January 2015. That normative moment has not only disappeared; the government leaders have forced it to disappear. It is very difficult to imagine a democratic state reform project being successfully carried out by a regime which has lost its ethical and normative bearings.