Editor’s Note: The following is a note prepared by the Spokesperson of the Foreign Affairs Ministry, Mahishini Colonne. This was in response to an interview conducted with Former External Affairs Minister G L Peiris, in which he made several claims about the bill to give effect to the International Convention to Protect All Persons from Enforced and Involuntary Disappearances. The interview made several incorrect assertions, including that the Bill will be subjected to the jurisdiction of the International Criminal Court. Below is the full text of Mahishini’s response, addressing some of the concerns flagged, and providing some facts about the bill.

- Why is there a need to criminalise ‘enforced disappearances’?

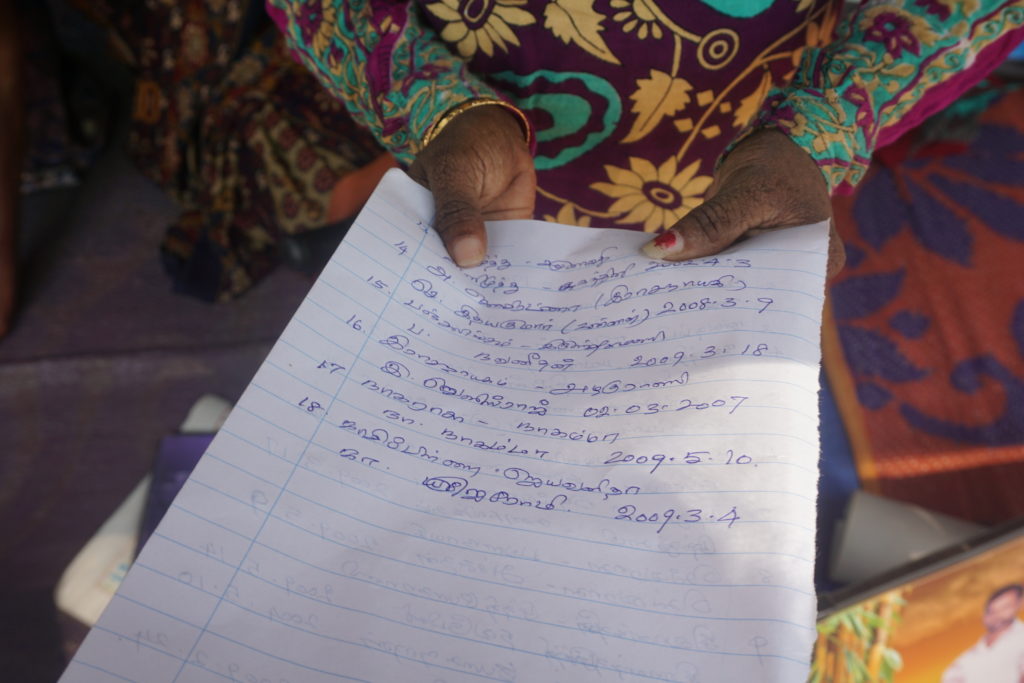

Sri Lanka has had a history of allegations of ‘enforced disappearances’, white van abductions etc. This is evidenced by the numerous commissions of inquiry which have looked into such allegations over many decades.

All citizens / persons have a right not to be subject to enforced disappearance.

This should be seen PRIMARILY as Sri Lanka’s responsibility to her own citizens. The aspect of signing the International Convention is secondary, and flows from the primary responsibility of Sri Lanka to her citizens.

2. What is an enforced disappearance?

The Offence is defined in section 3.

(1) Any person who, being a public officer or acting in an official capacity, or any person acting with the authorization, support or acquiescence of the State –

(a) arrests, detains, wrongfully confines, abducts, kidnaps, or in any other form deprives any other person of such person’s liberty; and

(b) (i) refuses to acknowledge such arrest, detention, wrongful confinement, abduction, kidnapping, or deprivation of liberty; or

(ii) conceals the fate of such other person; or

(iii) fails or refuses to disclose or is unable without valid excuse to disclose the subsequent or present whereabouts of such other person, shall be guilty of the offence of enforced disappearance…

Therefore in order to be an enforced disappearance, BOTH of the following elements must be present:

- there must be a deprivation of liberty as set out in part (a) (It should be noted that this not apply to ‘missing persons’ per se but only to those who are ‘disappeared’ or subject to ‘deprivation of liberty’); AND

- there must be a refusal to acknowledge the deprivation of liberty OR a concealing of the person OR a failure to disclose the whereabouts of the disappeared person

Section 3 also provides for the liability of NON-STATE actors, as well as superior officers who have direct control; willfully / consciously disregard information that their subordinated are engaging in enforced disappearances; or fail to take legitimate action to prevent same.

- Will this Act prevent the arrest of terrorism or other suspects, due to the way in which ‘deprivation of liberty’ is defined?

A fear has been expressed that the Act will hinder investigations.

“deprivation of liberty” means the confinement of a person to a particular place, where such person does not consent to that confinement;

However, the deprivation of liberty is not criminalised or prevented by the Act. As seen from the explanation of section 3, the offence is only established if there is a deprivation of liberty, COUPLED WITH a refusal to acknowledge the deprivation of liberty OR a concealing of the person OR a failure to disclose the whereabouts of the disappeared person.

Law enforcement authorities are entitled to arrest (in accordance with the law). This does not mean that arrested persons can be held in secret detention, because that would leave room for abuse, torture, extra-judicial killings etc. The Act will not hinder investigations.

- Will this Act result in the prosecution of armed forces or police personnel, for alleged offences committed during the Armed Conflict?

No. The Act does not have retrospective operation, and will only apply to allegations of enforced disappearances committed after the Act comes into force. The act is to prevent enforced disappearances in the future.

- Will the Bill result in International Prosecutions?

It is open to any country to prosecute for offences, if their law provides for same. This would be so regardless of this Act. However, by providing the legal mechanism for a domestic prosecution, it would be possible for Sri Lanka to argue that it is competent to prosecute in respect of domestic violations, and that there should be no international prosecutions (in an international tribunal) in respect of same.Section 6 specifically provides that the High Court of Sri Lanka shall have exclusive jurisdiction to try offences under the Act. Therefore, by enacting the law, Sri Lanka will be taking responsibility for the investigation and prosecution of alleged Enforced Disappearances committed within Sri Lanka, and thus be able to argue that the matter should not be prosecuted before International Fora.

- Who is a victim?

- The disappeared person

- Any individual who has been affected as a direct result of an enforced disappearance [section 25]

- What are the rights of a victim?

- To know the truth regarding the circumstances of enforced disappearances

- To know the progress and results of the investigations relating to enforced disappearances

- To know the fate of the disappeared persons [section 14]

- What are the rights of a person deprived of liberty?

- Not to be held in secret detention (i.e. not to be held in an unauthorised detention centre)

- Subject to the conditions established by law, to communicate with and be visited by his/her relatives, attorney-at-law or any other person of his/ her choice.

- That law enforcement authorities maintain registers of persons held in detention (this will reduce the incidence of secret detention / extra judicial killings)

- Why aren’t the provisions in the Penal Code sufficient?

The Penal Code deals with unlawful restraint and confinement.

However, the scope of this law is different. It deals with situations where the initial arrest may (or may not) be lawful, and goes onto require that the arrested persons not be held in secret detention, that his location not be concealed etc. Thus, the scope of the offence of Enforced Disappearance and unlawful restraint / confinement is different.

Rather than confining itself to creating a new ‘offence’, the objective of the Act is to create a culture in which Enforced Disappearances do not occur.

- Summary

In short, the objective of the Bill is to ensure that Enforced Disappearances do not occur. While there can be lawful arrests, persons must be held in lawful detention centres, and their arrest documented. This will prevent torture, abuse and extra judicial killings. Unless one intends to propagate a white van culture, or a culture of illegal abductions and / or killings, there would be no basis to object to the enactment of the Bill.

Editor’s Note: This note was published in full in today’s Daily Mirror.

The About Turn

The concerns flagged by the Joint Opposition represent a turnabout from one of its members, former President Mahinda Rajapaksa, who was once a passionate activist against enforced disappearances. For posterity, here are some of the comments he made, which have been entered into the Hansard:

In the Hansard of 25th October, 1990 in page 366 Mahinda Rajapaksa said, “I took the wailings of this country’s mothers. Do I not have the freedom to speak about them? It was the wailing of those mothers which were heard by those 12 countries.”

04th December, 1989 of page 941 – he thanked the government for permitting the ICRC to enter the country, and asked that the UN Working Group on Enforced and Involuntary Disappearances and Amnesty International be also allowed to visit Sri Lanka

In the Hansard of 25th October, 1990 in page 365 he said, “We asked the donors countries as to why conditions cannot be imposed when giving aid. That was the request we made. It is what has been fulfilled today.”

In the Hansard of 25th January 1991, “We went and told donor nations to cut these and these, and to tell this government to protect human rights of the people of this country.

In the Hansard of 25th October, 1990 in page 424 he said, “If the government is going to deny human rights, we should go not only to Geneva, but to any place in the world, or to hell if necessary, and act against the government. The lamentation of this country’s innocents should be raised anywhere.”

This position is a radical shift to the stance he took when the Office of Missing Persons Bill was being debated.

The Centre for Policy Alternatives has also compiled a guide to the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance, available here.