“Mewa dakala danwath meka nawaththuwoth monawa nathath, eka mokakhari”

(If they see these and put an end to this, if nothing else, that’s something)

The words of a Muslim man I met on my visit to Aluthgama, two weeks after the violence broke out in 2014 rang hollow as I returned to Aluthgama a few weeks ago, three years later.

“Kauruthma hitiye na geval wala… Raththarang badu okkoma aragena, vatina deval, deed okkoma aragena api giya. Api Gihilla sathiyak withara akkalage gedara indala thama awe”

(Nobody stayed in their houses… We took our gold, deed, everything valuable and left. We stayed with our sister for about a week and came back)

Those are the words of a woman in 2017, fearing a repetition of the same violence from three years ago on the 15th of June, 2014. Against the backdrop of a series of attacks on mosques and Muslim-owned businesses recently, and two arrest warrants for the General Secretary of the hard-line Buddhist group, the Bodu Bala Sena (who were the instigators behind the violence in Aluthgama in 2014), the Muslim residents fled for safety fearing backlash and fresh violence in 2017 from the agitated Sinhala minority community in Aluthgama.

Returning to Aluthgama three years later and walking the same streets was a surreal experience. The town had transformed to a point of unrecognisable. Burnt houses that were no short of slogans written in the soot calling for the BBS to be held to account, were now rebuilt by the Army with whitewashed walls and new kitchens.

A two-story house I photographed, where walking through room after room painted a fresh picture of violence with its burnt wood-work, furniture, sewing machines and bicycle, was now rebuilt with barely any indication of the destruction that was.

The grass appeared greener in another backyard, recovered after the debris of the violence had been dumped there for weeks.

A short, orange wall, vaguely reminiscent of the formerly vibrant, typically colourful houses down the road, stood at the entrance to a house, now painted a gleaming pure white.

A village mosque, worshippers admitted, was built much better than what it was previously, with added spaces for children’s religious studies.

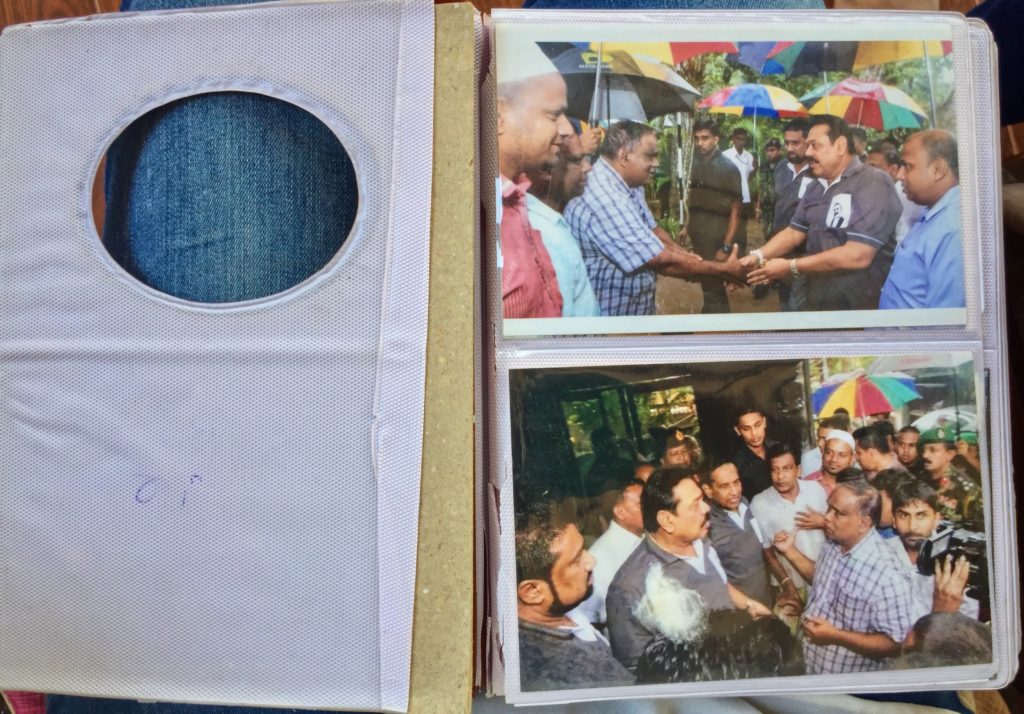

A resident eagerly showed a personal album of photographs of their old house, burnt down to pieces, complete with snaps of their vehicles set on fire. The damage was extensively and immaculately documented in the album, which I couldn’t help notice had little pieces of cotton wool inserted into some photo sleeves – an age-old trick to protect prints from going bad due to moisture. The album cover carried the title ‘Golden Collections’, and adorned a photograph of the former President extending his hand in good will to the proprietor. The irony didn’t escape me. It was the tacit approval of the then government and inaction against hard-line Buddhist groups that emboldened the audacity of the likes of BBS that culminated in the rampage in Aluthgama in 2014.

Some built better than before, some not yet finished. Residents claimed that their houses were however only ostensibly rebuilt, unconvinced that the real issue had been rooted out. Three families lost their loved ones three years ago and many of those injured struggle with the scars that remain.

Although tedious assessments had been carried out by government authorities to document the damage, there has been little to no compensation for the affected families for property damage. Worse still, perpetrators of the violence and the looting are still at large, with lawyers working on the cases alleging that law enforcement is deliberately delaying taking the cases forward. A citizen-led Foundation supports many of the affected get back on their feet, stepping in to provide assistance where the State has failed to fully compensate and provide reparations for victims.

Life goes on in Aluthgama, albeit a little differently.

Inter-ethnic and religious relations between neighbours have soured. Sinhala and Muslim families living side-by-side now feel suspicious, with Muslims wondering how the mobs had so much insight into which houses were Muslim-owned. A woman described her now tense relationship with her Sinhala neighbour who she grew up with. She said that because their family house was bigger than the Sinhala family’s next door, they even offered their house for their Sinhala neighbour’s wedding. It’s not like how it was before, she says, as awkwardness now consumes most of their interactions. The damage to community relations seems irreparable, at least for a very long time.

Residents are cautious and prepared in case of repeated violence. Aside from leaving their homes during the third anniversary of the Aluthgama attacks fearing repeated attacks, residents said they also keep their most valuable documentation (identification documents etc.) away from their houses for safekeeping. Basically whatever that’s necessary to start afresh next time all their homes and life’s earnings are destroyed and looted.

Similar sentiments were echoed in “Demons in Paradise”, a new documentary directed by Jude Ratnam reflecting (mostly) on Tamil militancy during Sri Lanka’s civil war. Although the scale and violence during 1983’s pogrom that resulted in many Tamils fleeing to the North for safety is by no means an equal comparison, a parallel in how the Tamil community felt, and arguably still feel today thirty-four years later, is starkly similar to how the Muslim community in Aluthgama still feel to this day: visitors in their own home towns. Even during times of peace, an unbeatable sense of fear overwhelms minority communities, not knowing when they will next be persecuted or hurt. This is no way to live. This is no way to reconcile.

“Apita hari sathutui Sinhala kattiya api gena balala mewa gena maadhyata liyana kota”

(It makes us very happy to see Sinhala people checking up on us and writing to media about these things), said one Muslim resident beaming away after stopping his bike curiously to see why I was taking photos of the newly-built houses. He was understandably surprised to see some continuing media interest in Aluthgama, since mainstream media in 2014 gave limited coverage to the incident, downplaying the extent of violence.

There’s however more to this issue than just a media blackout. While the Prime Minister condemned the recent violence against the Muslim community, the Minister of Justice seemed intent on denying the continuing violence against other religious minorities such as the Christians, going to the extent of threatening to take action to disbar an activist lawyer who shed light on the status quo. He seems unaware that acknowledgement, is the first step to positive change.

All the photos referenced in this story, taken in June 2017 can be seen here. All the photos from 2014 can be seen here.

###

Editors note: Also read The aftermath: Aluthgama two weeks on by the same author, published on 30 June 2014 and Aluthgama Three Years On, an interactive long-form photo story by the site’s co-editor, Raisa Wickremetunge, published in June this year. Ruwanpathirana’s 2014 article published on this site featured the very first photos of the devastation in Aluthgama after the anti-Muslim riots. Access those ninety-eight photos here, some of which have been featured in local and international reports, journals and news stories on the Aluthgama incident since 2014.