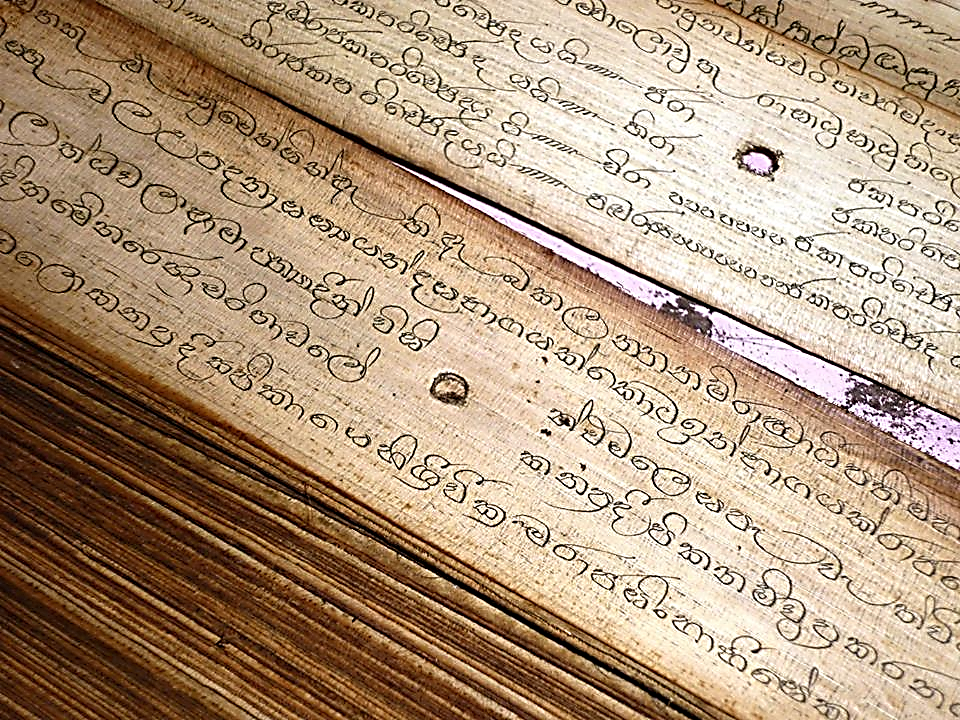

Featured image courtesy University of Kelaniya

Editor’s Note: The text reproduced below is the longer version of the introductory comments made at the BMICH, Colombo on 27th May 2017 at the announcement of the winner of the Gratiaen Prize 2016.

About Concerns of Judges

When speaking of the concerns we have as judges with regard to our experiences in judging the entries for the 2016 Gratiaen Prize, I am speaking on behalf of my fellow judges, Chandana Dissanayake and Ruhanie Perera as well. These are our collective thoughts. Over two decades, the Gratiaen Prize scheme has been an important system in providing recognition to writers in Sri Lanka who write in English. And this should continue. We already noted in April when the short list was announced that it would be best to institute separate award schemes for different kinds of creative writing in English on the same model as the H.A.I. Goonetilleke Award for Translations. Though difficult, this is not impossible if there is a willingness to work with other concerned entities and people who may share the same goals and ideals. This is primarily to offset financial burdens. This self-conscious diversification will limit the kind of subjectivity that necessarily seeps in now, as the system is way too open, and judges have to precariously navigate across varied genres of writing to arrive at ‘reasonable’ decisions. And that does not necessarily work too well all the time. The present scheme makes life difficult for both contestants and judges.

Ideally, the broad schemes and criteria for judging works in each category should be formally and clearly defined and publicly available so that contestants would know on what criteria they are being evaluated. But at the same time, there needs to be some leeway and flexibility for judges to be creative when needed, within limits. In other words, there is a need to have a more transparent and robust scheme with built-in possibilities of flexibility.

We also think that the Gratiaen Prize and other similar award schemes in the country need to ask themselves two fundamental questions: That is, should they be looking for the best creative writing in English in the country on par with global writing standards and norms? Or, should they be overtly moved by local conditions? If it is the latter, then, judges might often have to reduce global standards drastically – quite possibly against their better judgment – to deal with perceivably local conditions and idiosyncrasies. This simply cannot be good for the future of creative writing in the country.

As the Gratiaen Trust begins to celebrate its 25th anniversary while reflexively revisiting its important institutional history, we hope these issues might be thoughtfully explored so that a more reasonable scheme for evaluating creative writing in our country might be evolved.

On Creative Writing in Our Country

Let me take a few moments to reflect on the status of creative writing in Sri Lanka, but with a focus on prose. But I think what I have in mind can be generalised across all genres. These thoughts are based on my reading of Sri Lankan writing in Sinhala and English over the last couple of decades, and not by looking at the entries we received for the 2016 Gratiaen Prize. But these are simply my thoughts, and I do not want to implicate my two young colleagues in whatever politically incorrect I might say today.

I have often wondered why is it that Sri Lanka has not produced in contemporary times writers like Gabriel García Márquez, Umberto Eco, Fernando Pessoa, Pablo Neruda, Faiz Ahmed Faiz, Rohinton Mistry, Salman Rushdie, Elif Şafak, Orhan Pamuk and so on. Admittedly, these choices are based on my own subjective interests and taste. But all these are globally recognized writers of creative fiction from different parts of the world.

When I am asking such a rhetorical question, I am also asking why is it that our creative writing in general – whether short stories, novels, poetry and so on – lag so far behind in terms of global norms, and particularly with regard to recognition? I can answer this question by focusing on four specific and inter-related areas of concern:

1) One is about the time spent on creating a work, and the nature of exposure a writer might have to the expansive world of writing;

2) The second has to do with the use of language;

3) The third concern is what appears to be a limitation of imagination in working out plots and ideas;

4) The fourth is the relative lack of attention to research and a pronounced disinterest in broader domains of knowledge.

All of these are inexorably linked, and inattention to one, would obviously affect the others, and the work as a whole.

On Time Spent in Creating a Work

As I read Sri Lankan fiction and poetry in general, I don’t get the sense that most people have spent as much time as they ideally should in working out the structure and details of what they write. Many seem to be in a mighty hurry to finish, publish, and win awards. And it does not help that we hardly have a professional publishing industry in this country with competent systems for vetting and reviewing. As we know quite well, publishing often depends on the personal connections a writer has with publishing houses, and the commercial interests of these publishers. In this scheme of things, quality of writing is not always a major concern. This means that writings, which have not achieved the necessary quality due to lack of investment in time and effort and have not fulfilled other essential criteria, can easily be published. They might even win local awards.

Unfortunately, many of us – be they writers or not – are also not too keen to broaden our horizons, by reading widely. If one reads, Fernando Pessoa’s work, The Book of Disquiet, how can one miss what Phillip Pullman has called “mysteries, misgivings, tears and dreams and wonderment” within the book’s 260 odd pages? If you read Vikram Chandra’s Red Earth and Pouring Rain, his first novel, one can see he is a master narrator of stories, moving Adam Thorpe to caustically comment that Chandra’s novel “makes its British counterparts look like apologetic throat-clearings.” Similarly, Umberto Eco’s Prague Cemetery, convincingly deals with 19th century Europe – from Jesuit plots against Freemasons to Italian republicans strangling Catholic priests with their own intestines, and so on.

All these have become memorable works of fiction primarily due to the time the writers have taken to perfect their art, to fine-tune their narrative styles, do essential research and build the necessary background.

What is stopping us from bringing such well-established global milestones to bear upon what we write locally? In the prevailing circumstances, if we go beyond our islanded frame of mind, and situate some of our hurriedly produced works without any seeming inter-textual sources of inspiration in a global scheme of reckoning, how would they fare? Would they make a mark in a far more competitive environment? But then, why should one even attempt for such greater heights when we can manage with much less, right here?

I leave these questions unanswered for you to think about.

On the Issue of Language

By and large, in much of the Sri Lankan writing I have read, I don’t see a passion or a serious engagement with language or radical experimentation with different forms of writing.

This is not about using correct spelling or grammar. In many cases, language is either economical, fed by an unfortunate limitation in vocabulary, or it’s simply dry. Not much time or effort is taken for essential description, to build up stories, or construct conversations. Or, it is forced, and wordy. By and large, one also cannot see much reflection and thinking when it comes to creatively dealing with various forms of writing as well. There is not much interest to work across genres. All these shortcomings, I think comes when language is merely used as a utilitarian device for the primordial act of communication, and clearly devoid of passion, color, emotion, imagination and feeling. How often do you see passages like the following in Rushdie’s The Enchantress of Florence in our writing?

“A week after his final refusal, Marco Vespucci hanged himself. His body dangled from the Bridge of Graces, but Alessandra Fiorentina never saw it. She braided her long golden tresses at her window and it was as if Marco, the Fool of Love were an invisible man, because Alessandra Fiorentina had long ago perfected the art of seeing only what she wanted to see, which was an essential accomplishment if you wanted to be one of the world’s masters and not its victim. Her seeing constructed the city. If she did not see you, then you did not exist. Marco Vespucci dying invisibly outside her window died a second death under her erasing gaze.”

I will not over-stress my point. But as fellow readers, I think you can grasp what I am concerned about.

On Limitations in Imagination

When specifically thinking of fiction set in defined historical or mythical epochs, examples that instantly come to my mind are Marquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude, Eco’s Prague Cemetery, Elif Şafak’s The Architect’s Apprentice and Orhan Pamuk’s The Museum of Innocence.

These are simply unconnected references that are stuck in my mind due to the ways in which they have used history, notions of the past or memory to develop their plots with a nuanced sense of imagination to narrate their tales. There are many other examples.

Our written histories are replete with many possible and quite intriguing points of departure, which could ideally allow us to write good historically rooted fiction. But we don’t seem to ask the right kind of questions or allow our imagination to blossom within the realms of possibility. For instance, why shouldn’t one of our novelists ask: Are Dipavamsa, Mahavamasa and Chulawamsa the only preeminent records of historiography?

Within the frame of that question, what about the fictional possibility of a secret, not yet discovered, but possibly existing record of our history which local monks had spirited off to Nalanda for safe keeping in times of local calamity, which was in turn taken to China by the pilgrim monk Xuan-zang during his 18 years of travel across the region from China to India and back, before the ultimate and complete destruction of the Nalanda library and the main complex itself. Xuan-zang’s descriptions of Buddhist sites in ancient South Asia are among the most complete accounts one can find, and he dreamt of coming to Lanka, but could not.

Within these possibilities, what is stopping one of our own from writing a work of fiction in which the story line might suggest that our understanding of local history would radically change if this lost manuscript languishing in some godforsaken Chinese monastery in the Sichuan Province was found? That could be a fascinating journey into history, the intrigues of present day politics, and the world of myth and belief while allowing creative imagination to blossom. When I wonder about these fictional possibilities, I often think about books like Umberto Eco’s Name of the Rose or Jostein Gaarder’s Vita Brevis: Letters to St Augustine both of which engaged with history deeply to weave their narratives. But closer to home, it seems to me that Prof Gananath Obeyesekere’s recent book, The Doomed King: A Requiem for Sri Vikrama Rajasinha, which offers a creatively revisionist history of 19th century Lanka with a focus on our last king, presents tremendous possibilities for creative writers interested in historical fiction.

But to ask such questions, and to allow one’s creative imagination to soar, we must be exposed to the broader worlds of global writing and domains of specialised knowledge, such as the historical records that Prof Obeyesekere has consulted in our own context, and Xuan-zang’s detailed travel accounts, all of which are now published and available in English. But above all, to do all this, one must have reservoirs of patience and time.

On the Issue of Research

In my mind, no creative writing is possible without sound background research. As a novel, Rohinton Mistry’s Such a Long Journey, foregrounding the life of Mumbai’s Parsi community and India’s nationalist politics of the 1970s would not have been possible, if not for the thorough research on Indian politics and demographic transformations undertaken by Mistry. Similarly, Baudolino would not have worked if not for Umberto Eco’s considerable grasp of Christian and European history of the 12th century. Similarly, Eco’s Name of the Rose has become what is, due to the author’s sound grasp of medieval European history, semiotics, biblical analysis and literary theory.

To reiterate, it is due to sustained research that these novels and many others like them, have been able to successfully create the overall context and mood within which they flow, and have acquired global recognition.

But knowledge of this kind has to be self-consciously sought, and the only method for doing this is through extensive research. There are no short cuts. Such knowledge does not merely come from quotidian experience, by reading the morning newspapers, casual online loafing and certainly not through divine or demonic intervention.

In these times of uncritical and populist nationalism, some of you might say I am being unreasonable, unpatriotic, and we write as well as anyone else. To friends and colleagues with such reservations, my only question is this: how come our writing in English has not become a global presence – barring a very few exceptions? Why was it necessary that many writers with Sri Lankan family connections had to first leave our shores to become globally ‘recognised’? Is it a massive conspiracy against us by the rest of the English-speaking world?

More realistically, I would say, the answer lies in our collective inattention to the four areas of concern I just outlined. But obviously, there are many other issues as well, which I have not discussed today. In any event, without the ability to be self-critical and reflexive of our predicaments, we simply cannot go beyond the often self-defeating systems of reckoning presently in place in our country. No system of evaluating creative writing should be obliged to offer awards annually as a matter of ritual. Let there be dry spells for a year or two or more, if entries that fulfill basic global norms are not received for consideration. As we have already noted, it is a serious mistake to have systems for evaluating creative writing too closely anchored to local conditions and idiosyncrasies. After all, we compete with the world successfully and on an equal footing in areas like visual art, film, architecture, cricket and political violence. So why not writing? The local can inspire us, and it certainly should; but we must necessarily write for the world, particularly if we write in English. My point is if we offer an award to one of our own locally, he or she should also be able to compete with global award schemes with the same entry. If this is not possible, then there is something very wrong in what we do.

I have said all this today for a reason. It is not to dampen your spirits, but to make a plea for our collective future in writing. Including the Gratiaen Prize, we have systems of reckoning focused entirely on the end product of the creative process. That is, the focus is on ‘awards.’ We have almost no regular and institutionalised systems in place to help budding writers to get their craft right; to discuss the kind of things I have outlined, and to offer ways to deal with these. How can we offer awards without first clearing the avenues to get there? This is not something that can be done with irregular efforts by a handful of concerned individuals. I think it is essential that such systems of ‘training’ and exposure be made available to younger and aspiring writers on a regular basis – be it by the Gratiaen Trust or other concerned entities. But it must be done. I am not arguing that workshops will create good writers. But I am saying that such efforts will offer young writers exposure to people who know their craft and may work as regular sources of inspiration. This is what in certain ways, India’s Jaipur Literature Festival has done over the years primarily due to its policy of free access, and Lanka’s Galle Literature Festival has failed to do for precisely the opposite reasons. Given my present location, this is something I can help with, if there is adequate and serious interest.

I think I have said enough for one evening. And I am sure my position is clear enough whether people opt to agree or not.

(Sasanka Perera is Professor of Sociology and Vice President at South Asian University, New Delhi and Chairman of the Panel of Judges for the Gratiaen Prize 2016)