Featured image courtesy the Hindu

Editor’s note: This is an edited version of an article which originally appeared in The Daily FT on 16 May 2017.

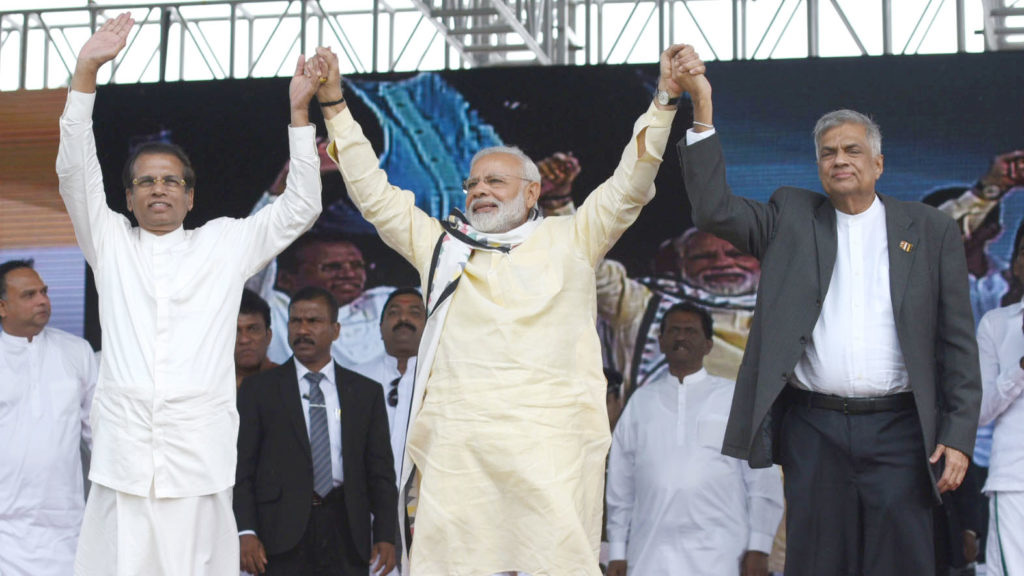

Last Friday (12 May) Sri Lankans living in the central hills lined its narrow streets to catch a glimpse of that Indian tea-seller who rose to become the Prime Minister of India. The crowd, comprising of Tamils of recent Indian origin, were visibly jubilant. They turned up, in the thousands to hear Narendra Modi speak at Norwood Grounds after the opening of a new hospital complex in Dickoya, built with Indian funds.

The euphoria and indeed affection was clearly palpable. It was a rousing welcome befitting a celebrity. The visiting Indian Premier, reacting to the warm reception, tweeted: “On the road in Sri Lanka… overwhelmed!”

On the road in Sri Lanka…overwhelmed! pic.twitter.com/0j7dZDk1op

— Narendra Modi (@narendramodi) May 12, 2017

It was Modi’s second visit to Sri Lanka since his election in 2014 as India’s Prime Minister, but more significantly, it was the first visit by an Indian leader to the central hills, where Up-country Tamils or Tamils of recent Indian origin are concentrated.

No other Indian leader has visited the hill country since indentured labour was brought from south India by the British colonial rulers (initially for coffee, and then for their tea and rubber plantations) in the 19th century.

In the past, Indian leaders have considered a visit to the North of the island as an essential part of their itinerary, their attention primarily focused on the Tamil community in the North and East of the island. This, of course, was induced by pressure from Tamil Nadu on the Indian central government to persuade Colombo to address the ethnic issue.

Though Modi’s visit was widely seen as an apolitical one, a handful of Sinhala nationalists were resentful. There was a call to hoist black flags in view of the Indian Prime Minister’s visit – a call that went totally unheeded by the vast, rational majority. Up-Country Tamils were also provocatively referred to as India’s ‘fifth column’ in Sri Lanka. But importantly, and beyond these misplaced fears, Narendra Modi’s visit turned the spotlight on a distinct community that has been largely neglected by successive governments in post-independence Sri Lanka.

With hardly any economic or political clout, the plantation community have lived for centuries in appalling, even sub-human conditions, in squalid plantation line-rooms. Their marginalised status was acknowledged in the National Action Plan (NAP) for the Social Development of the Plantation Community 2016-2020 formulated by the Ministry of Hill Country New Villages, Infrastructure and Community Development. With reference to the Household Income and Expenditure (HIES) reports of the Department of Census and Statistics (DCS), the NAP in its Executive Summary noted:

“The estate sector is the most deprived sector in terms of social development with poverty, education, health, nutrition, housing, safe drinking water, sanitation and women’s empowerment being areas of concern. Hence, from a national perspective there is a need to strongly focus on developing the plantation community to ensure that they are in par with the rural and urban sectors on MDGs [Millennium Development Goals] and SDGs [Sustainable Development Goals]. It is also understood that this community has not been integrated into the national health, education, housing and other service delivery systems of the government.”

The 2012/13 HIES/DCS poverty head count which measures the percentage of the population below the poverty line, showed a poverty headcount index of 6.7% (i.e. percentage of the population below the poverty line) at the national level. The highest poverty head count index was reported from the estate sector at 10.9%.

The HIES/DCS report further showed that 54.7% of the estate sector households were among the poorest 40% households in the country. The estate sector is therefore unique in terms of income disparity and still lags far behind in relation to the other sectors in the country.

In his address to the plantation community on Friday, India’s Prime Minister drew attention to the important (but often under-valued) role played by them in the production of tea thus highlighting their contribution to the country’s economy. In the presence of President Maithripala Sirisena and Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe, Modi struck an instant chord with his audience when he said:

“If Sri Lanka today is the third largest exporter of tea, it is because of your hard work. It is your labour of love which is instrumental in Sri Lanka meeting almost 17% of the world’s demand for tea, and earning more than 1.5 billion US dollars in foreign exchange. You are that indispensable backbone of the thriving Sri Lankan tea industry that justly prides itself on its success and global reach today.”

In real terms tea exports had been Sri Lanka’s number one earner of valuable foreign exchange since independence, until foreign employment brought it down to second place during the last three decades. There is no doubt that the estate sector workers are “the cogs in the large machine that is the tea industry of Sri Lanka,” as Amalini De Sayrah puts it in an excellent photo story for the Centre for Policy Alternatives (2015) entitled ‘Up-Country Tamils: the forgotten 4.2%’.

To this poorest section of Sri Lankan society, the Indian Prime Minister promised another 10,000 houses in addition to the 4,000 his country is already funding. Modi tweeted: “Glad that Sri Lanka’s Government is taking active steps for improving the living conditions of Tamil community of Indian origin”.

The Minster of Hill Country New Villages, Infrastructure and Community Development P. Digambaram told Al Jazeera from Dickoya on Friday, “India has a duty to look into our well-being because we are of Indian decent”.

His words stood in stark contrast to the sentiments expressed by retired Rear Admiral Sarath Weerasekara who told the media (Daily Mirror, Saturday 13 May) that focusing on one ethnic population could adversely affect reconciliation in the country. He claimed that the resources of a country had to be divided among its citizens equally and that Modi’s favouring one ethnic group over another was setting a bad example to the world and other ethnicities in the country.

Weerasekara’s comments are indeed surprising. Sri Lanka’s economy has benefited immensely from the contribution of the plantation Tamil community, yet they have not been compensated in due proportion. Weerasekaras regrettably never drew attention to the failure of successive governments over the past 70 years to ‘divide equally the country’s resources’ amongst all sections of the island’s population.

The Indian intervention to assist this neglected or exploited set of human beings by providing them their greatest need, decent housing with wash room facilities, though no great honour to Sri Lanka, is a laudable humanitarian act.

There is certainly a need to favour disadvantaged groups; they need recognition and special help to enjoy an equitable status on par with the other communities. It is an indictment on all of us that despite nearly seven decades of independence, the plantation sector remains an impoverished group far behind all others on all developmental indices. Had governments of yore discharged their responsibilities, we might not have been in a situation which necessitated Indian help today.

With baffling priorities like squandering millions on luxury vehicles to enrich the political elite, this can be hardly astonishing. It is difficult to question India’s interest in them when we have done so little to uplift this community for so long. If this government delivers on the promises in the National Plan of Action and addresses the needs of this marginalised community, they may not require such external assistance in the future and none need to imagine the cuddling of fifth columnists.

Readers who enjoyed this article might find “Plantation Community: a status revisit” and “The other side of Narendra Modi’s Sri Lanka visit” enlightening.