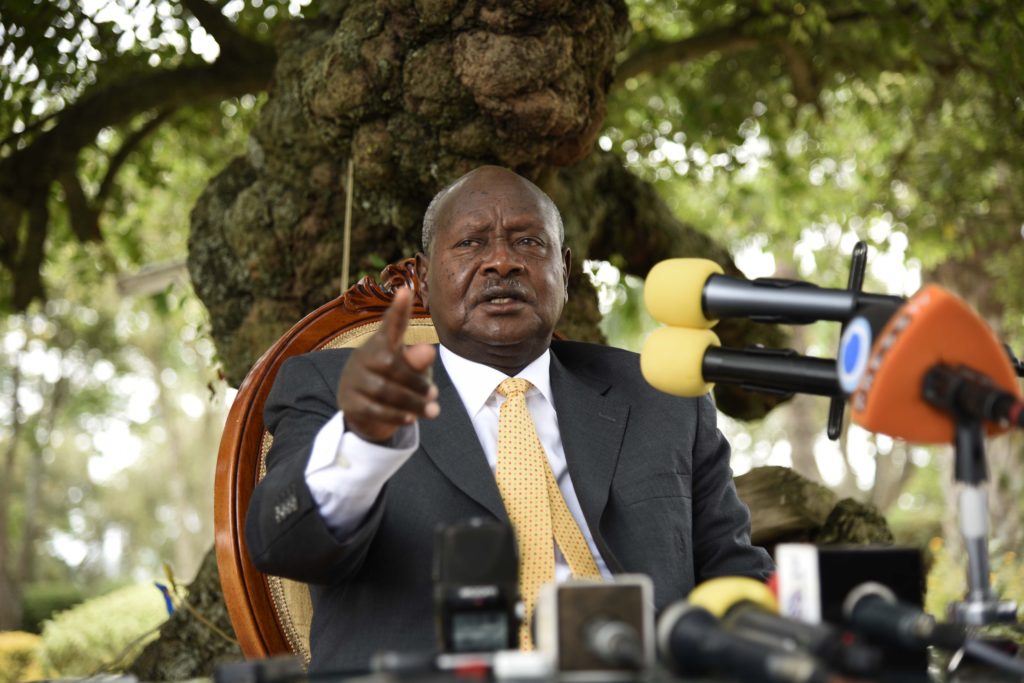

ISAAC KASAMANI/AFP/Getty Images via IB Times

“Sometimes a pebble is allowed to find out what might have happened – if only it had bounced the other way.”

Terry Pratchett (Jingo)

Former President Mahinda Rajapaksa is unlikely to know the poem or the poet, but the sentiments would have been his as he watched Uganda’s Yoweri Museveni swearing in as president for the seventh time.

‘For all the sad words of tongue or pen,

The saddest are these: ‘It might have been!’’[i]

Mr. Museveni’s seventh consecutive investiture (he has been in power since 1986) was as controversial as the election he purported to win. A clamp down on dissent kept Uganda quiet and silenced the social media, the final frontier of dissent. His main opponent, opposition leader Kizza Besigye, was arrested, flown to a remote corner in the country and formally charged with treason. His crime was casting aspersions on Mr. Museveni’s victory and the charge carries the death sentence.

Kizza Besigye is a member of what is known as the ‘Bush Generation’; a physician by profession, he was Mr. Museveni’s personal doctor during the guerrilla war which propelled the latter to power. Mr Museveni was once a popular leader (and a darling of the West) credited with bringing peace and stability to a war-torn country. He was initially critical of leaders who cling to power forever but changed his tune gradually as his political appetites grew. Mr Besigye was a key member of the Museveni government for more than a decade before joining the opposition.

During his seventh investiture, Mr. Museveni was surrounded by a phalanx of other long-ruled African leaders, leaders who have no intention of leaving power so long as there is a breath left in their aged bodies. Some of them nurse dynastic dreams (Mr. Museveni is accused of promoting his son as his successor); all of them rule over lands where democracy is a cover for one party rule and elections can have only one, utterly predictable, outcome.

Human beings tend to get used to the most atrocious of circumstances, with time. They can be taught to abandon ideals and dreams, and focus on survival and managing. Once the message of ‘support me and you will prosper; oppose me and you will suffer’ has seeped into the collective consciousness of a nation, popular dissent becomes near impossible. People try to get on with their lives to the best of their ability, allowing leaders to rule as they will.

Uganda seems to have reached this point of indifference. Ugandans are reportedly reacting to Mr. Museveni’s ‘victory’ with neither joy nor defiance, but lethargy; a shrugged shoulder rather than smiles or tears. “Ordinary Ugandans are not celebrating this, but neither are they grieving or protesting because there seems an inevitability of his dominance, even though the elections have been condemned by the European Union and other Western powers… Those who support Museveni have access to jobs and contracts, while his opponents are totally neglected… These sit-tight dictators also rule by fear, intimidation and violence. A mystique of life and death surrounds these presidents for life. They are demi-gods and political demagogues, whose words and wishes are commands in their countries. They are also vampires who suck up blood and life from their country and from their opponents. Uganda revolves around Museveni. He gives life and he can also give death, those who adulate him enjoy some portion of the national wealth, and those who loath or oppose him suffer.”[ii]

That was the path Sri Lanka was on, when January 8th intervened.

Mr. Rajapaksa’s thoughts would have been bitter indeed as he watched his brother-leader swear in for the seventh time. This was what he had in mind for himself. This was the future he planned for and worked towards. This was why he nullified the 17th Amendment, brought in the 18th, cowed the judiciary and repressed the media. This was why he effaced the lines of demarcation between state and ruling family.

Mr. Museveni could have been him. Uganda could have been Sri Lanka.

Mr. Rajapaksa went to Uganda with a substantial entourage of acolytes. His secretary is said to have written to the Foreign Ministry asking the government to defray the costs of this junket, including airfares, food and lodging[iii].

Defeat has not taught Mr. Rajapaksa any positive lessons. He still believes that he is the state/nation, and there should be no difference between public and familial finances. He still regards power as his due. The sole purpose of his politics is to push and cajole Sri Lanka into becoming a faux democracy again, a country in which a multiplicity of political parties, periodic elections and a parliament are nothing but props and camouflages for rule by one family.

Saviour-leaders and Salvationist Politics

In the US, Donald Trump, the orange-haired billionaire whose claim to fame includes a string of spectacular business failures, is about to become the official nominee of the Republican Party. Mr. Trump, in his obsessive desire to gain the presidency, has embraced Salvationist politics, portraying himself as the political saviour of white Christian Americans. In this advocacy of government of, by and for the ‘chosen people’, chosen on the basis of a primordial identity, Mr. Trump is no different from the Islamic State (IS) or fundamentalists of any other religion or race. From orient to occident, extremists of every race and fundamentalists of every creed have a similar aim – the purification of the land (reinen in the Nazi parlance) by evicting/suppressing the racial, religious or politico-cultural ‘Other’.

Religion and race form an important weapon in the arsenal of leaders for life. Mr. Museveni, for example, is an evangelical Christian who is identified with the powerful American sect, ‘The Family’. The Family is an ultra conservative evangelical church based in Washington DC and Mr. Museveni is said to be its key man in Africa.[iv] He uses ‘moral crusades’ to divert public attention from real issues and to demonise some of his opponents. Perhaps the best case in point was the punitive bill of 2014 against homosexuality (like in most parts of the Third World, homosexual ity was transformed from a private choice into a public crime by colonial rulers). Such campaigns enable leaders for life to change the focus on politics and public discourse from issues such as democracy, cost of living, poverty and corruption to ‘morality’. It is also an extremely effective way of displacing blame (some American evangelicals blamed Hurricane Katrina and its devastative aftermath on the immoral choices made by some Americans) and creating enemies.

In Sri Lanka, before Black July and the long Eelam War, there was the myth of the encroaching Tamil who was taking over ‘our’ schools, ‘our’ universities and ‘our’ government jobs. Today there are similar whispers about the moneyed Muslim who predominates in ‘our’ shops and ‘our’ holiday resorts. In between there was – and will be – grousing about the insidious Christian who is converting ‘our’ people. During their nine year rule, the Rajapaksas tried to exacerbate these phobias and benefit from them. That effort continues in the work of the Joint Opposition and its attempt to return Sri Lanka to Rajapaksa rule.

Prejudice and intolerance are not the preserve of one people, but the common bane of every race and religion. When the LTTE expelled Muslims en masse, very few Tamils protested. In some Muslim majority areas in the East, adherents of more extremist variants of Islam (especially Wahabism) attack and victimise fellow Muslims they consider to be improper Muslims or non-Muslims. Such facts are both undeniable and immaterial. The rights of minorities (or any discriminated community) should be protected and fought for not because they are good people but because they are people, fellow human beings like us. It is precisely this common humanity that extremists of every race, fundamentalists of every creed object to and deny. That denial – and the exclusionary politics based on it – forms an indispensable pillar of their power project.

American columnist Adam Gopnik in a recent piece itemised common characteristics of politics of salvation. “…an incoherent programme of national revenge led by a strongman; a contempt for parliamentary government and procedures; an insistence that the existing government….is in league with evil outsiders and has been secretly trying to undermine the nation; a hysterical militarism…; an equally hysterical sense of beleaguerment and victimisation;…failure, met not by self-correction but by an inflation of the original programme of grievances, and so then on to catastrophe.”[v]

And always the need for the enemy within and without, some enemy, the enemy who necessitates the existence of a saviour.

That was how the Rajapaksas ruled. That is how they plan to regain their rule.

But there is one precondition without which the Rajapaksa power project has little chance of success: economic pain of the masses. With its punitive taxes, the Sirisena-Wickremesinghe administration is busy delivering that crucial precondition to the waiting arms of the Rajapaksas.

Economics and Politics

Historically politics of salvation has achieved success almost always in times of economic discontent. When economic growth or recovery happens at the cost of the poor and the middle classes, when relative poverty increases deepening the gulf between the haves and have-nots, when solemn promises about economic relief are broken by politicians, alienation results. And alienation makes a segment of the populace vulnerable to appeals of extremism and to the inevitable searches for ‘scapegoats’. In multi-ethnic and multi-religious countries such as ours the extremisms are usually based on ethno-religious identities while the ‘scapegoats’ are naturally the ethnic/religious ‘other’. From that to instability and upheaval, violence and bloodshed is only a short step.

Dysfunctional economics is a threat to political stability and democracy. The unwillingness of major Western powers and international financial institutions to abandon their insistence on economics of austerity and to do for the Middle East what was done for the war-devastated Western Europe through the Marshall Plan played a significant role in the undermining of the Arab Spring and its replacement by a brutal winter of extremism. A somewhat similar drama is in the making in Sri Lanka. The government’s new economic regimen – imposed on it by the IMF – threatens to undermine its credibility and legitimacy, and enable the pro-Rajapaksa opposition to find its way out of the rubbish heap of history.

As economic austerity begins to bite, the Sinhala-Buddhist majority’s receptivity to the violently intolerant political creed of the Rajapaksa clique will increase. The Rajapaksas, like Donald Trump, will portray themselves, again, as the saviours of victimised Sinhala-Buddhists, betrayed by an ‘anti-national’ government which is on the side of the minorities, India and the West. That Rajapaksa gamble may or may not work, electorally. Either way, it will undermine the post-January 8th gains in the areas of democracy and ethno-religious reconciliation and turn Sri Lanka into a more divided, more intolerant and more violent land.

A UPFA parliamentarian who is a member of the pro-Rajapaksa Joint Opposition became the first to cash in on the vehicle bonanza – he imported a vehicle worth Rs.40 million and paid the princely sum of Rs. 1,750 as import taxes[vi]. Unfortunately such anomalies would matter little when atavistic fears rule and ethno-religious agenda is predominant. In any case, government members too will rush to avail themselves of this bonanza. The electorate does not expect honesty or probity from the Rajapaksa clique. But the government won by advocating a higher standard, and will be judged in accordance, come election time.

[i] Maud Muller by John Greenleaf Whittier

[ii] http://www.huffingtonpost.com/stan-chu-ilo/musevenis-flawed-election_b_9349490.html

[iii] Columnist Dharisha Bastian reports that Mr. Rajapaksa’s secretary, Uditha Lokubandara wrote to the Foreign Ministry twice making these demands and that the Ministry has agreed to pay Mr. Rajapaksa’s airfare. She also points out that there is neither a law nor a tradition mandating such a payment for a former president on a private tour. http://www.ft.lk/article/542074/Old-habits-die-hard-for-Mahinda

[iv] http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=120746516

[v] http://www.newyorker.com/news/daily-comment/going-there-with-donald-trump

[vi] http://www.island.lk/index.php?page_cat=article-details&page=article-details&code_title=145050